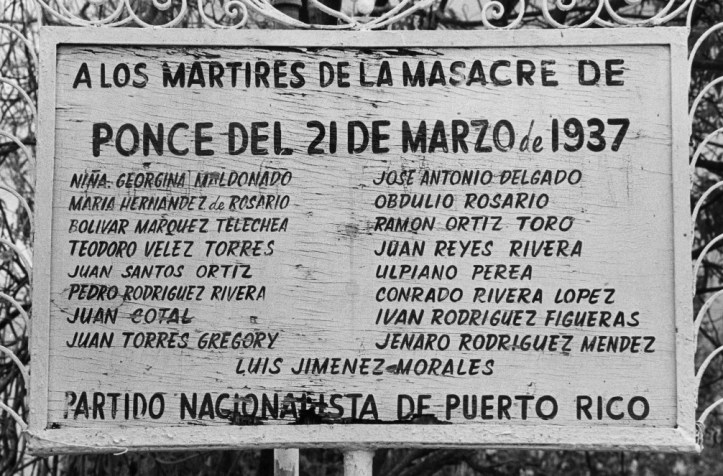

An essential historic document on the ‘Ponce Massacre’ in Puerto Rico of March 21, 1937. This exposure of the official lies covering-up the police murder of seventeen Nationalist Party marchers commemorating the end of slavery in Puerto Rico comes from an investigating committee led by the A.C.L.U.’s Arthur Garfield Hayes. The island was then ruled by Governor Blanton Winship, the Macon, Georgia-born former football player and career-military veteran of the Spanish American War sent to colony by F.D.R. to suppress the island’s labor upsurge hitting the empire’s super profitable sugar plantations, and its growing nationalist movement.

‘The Official Murders in Puerto Rico’ from New Masses. Vol. 23 No. 11. June 8, 1937.

The findings of the Hays investigating committee reveal hair-raising brutality on Palm Sunday and a lying cover-up by Governor Winship

Sections from the Investigators’ Report

ON MAY 13, Arthur Garfield Hays arrived in Puerto Rico as representative of the American Civil Liberties Union to head a non-partisan investigation of the massacre at Ponce last Palm Sunday. Twenty people were killed in that massacre and almost two hundred wounded. The committee headed by Mr. Hays has now completed a report on its findings. It is one of the most smashing indictments of imperialist rule ever to see the light of day in our times. The full report runs to about thirty thousand words, too long for publication in the NEW MASSES. From it we have selected only those portions directly bearing on the massacre itself and on the responsibility for it. These have been translated from the Spanish version of the report by our correspondents in Puerto Rico, Eduardo and Benigno Ruiz, and are the first-published English version of the most important sections of the report. The sub-headings are our own.

Besides Mr. Hays, the members of the investigating committee were persons of unquestioned integrity and high standing in the Puerto Rican community. They were Mariano Acosta Velarde, president of the Puerto Rican Bar Association; Manuel Diaz Garcia, president of the Puerto Rican Medical Association; Lorenzo Pineiro, president of the Teachers’ Association; Emilio Beleval, president of the Athenæum; Davilla Ricci, assistant editor of the Mundo; Francisco M. Zeno, editor of the Correspondencia de Puerto Rico; and Antonio Avuso, editor of the Imparcial. THE EDITORS.

THE NATIONALIST PARTY

THE Nationalist Party is composed of men animated by a fanatical spirit that carries them to complete self-immolation. Apparently they consider the highest ideal is to die for one’s country. The party is made up largely of young men. They use militant language and threaten to realize their end by means of force and revolution. They form groups and committees called Juntas Municipales and Juntas Nacionales, and they even send plenipotentiaries to foreign countries. Some of the Nationalists belong to the so-called Ejército Libertador (Army of Freedom); and for this purpose they teach military tactics. The members of the Ejército Libertador wear, at their parades, uniforms consisting of a black shirt and white trousers, with a small cap cocked jauntily on the side of the head. They use the Puerto Rican flag, not the American, and they sing the “Borinqueña,” not the “Star-Spangled Banner.” The spirit of these men is kindled by the demand for self-determination for Puerto Rico. They don’t ask for liberty as a gift, but demand it as a right.

Government authorities speak of the Ejército Libertador as though it were a military force. They suggest that unless precautions are taken, the “army” will use arms. It is the unanimous conclusion of this committee that the so-called Ejército Libertador does not use arms; that it does not have arms; that it lacks what is essential for any army: military armaments.

Its true arms are those of propaganda, which is so fiery and intemperate that it has led some individuals to commit crimes, even to assassinate. Breakers of the law have been punished. On one occasion, the assassination of an American official was so atrocious that both the Puerto Rican and the American people were horrified. This official was held in high esteem in Puerto Rico. The effect of this crime, however, was somewhat dissipated when the assassins were killed by the police. The Puerto Ricans rightly believe that the police have no right to violate the law, that vengeance does not form part of their duties, and that a well-trained police force should take such care of those under arrest that the latter will feel safe in the custody of the police. It was said that the prisoners reached for some guns.

They shouldn’t have been put in a room where there were guns.

Under the pretext, however, that the Nationalists, who are comparatively few in number, are gangsters who may use force, and assuming that they have military arms, the government authorities believe, or pretend to believe, that all sorts of precautions are necessary to avoid bloodshed. One of these precautions seems to be the prohibition of public meetings and assemblies, not only of the Nationalists, but also of other groups…

THE MATTER OF THE PARADE PERMIT

Several days before March 21, 1937, the Nationalists made public a statement that they planned to hold a parade in Ponce, and that, on the evening of that same day, they would hold a public meeting in the plaza. Apparently the government and the police were very wrought up over the suggested “provocation.” The Nationalist Party, through the Junta Municipal of Ponce, asked the office of the mayor for a permit, although the municipal ordinances of Ponce require no permit whatever…Nevertheless, an application was made for a permit. The mayor of Ponce was away. He had been in San Juan for several days. The Junta communicated with the acting mayor, who refused to assume the responsibility of granting the permit.

On Saturday night, March 20, the mayor returned to Ponce. After having consulted the local Nationalist leaders, he agreed to grant a permit for a parade of a civic nature, indicating specifically that no military parade should be held, whatever the meaning of that phrase may be.

Colonel Orbeta, chief of the Insular Police, arrived in Ponce Sunday morning. He was there several days before consulting prominent citizens who advised him, after he had advised them, that the parade and meeting would be dangerous. The local chief of police, Captain Blanco, had written a letter to the Nationalists, dated March 20, in which he told them that “in pursuance of instructions that I have received from my superiors, the police will oppose the holding of the events, and it is my duty so to advise you.”

Prior to March 21, and especially on that day, there was a considerable concentration of police forces in Ponce. The men were well armed with rifles, riot guns, sub-machine guns or repeating guns (known as Thompson guns), tear-gas bombs, revolvers, clubs, all the paraphernalia of force. Ordinarily, Ponce has a police force of thirty-five men; the number in Ponce on that day was between one hundred and fifty and two hundred.

Colonel Orbeta discussed the situation with Captain Blanco. They decided to find out whether the mayor had granted the permit and to insist that he revoke it if it was granted. Colonel Orbeta said he was tired of running all over the island every Sunday and that something had to be done to put an end to this; that some days before, he had conferred with government officials who had decided that it would be dangerous to permit the parade.

The mayor was not found immediately. Around noon, Colonel Orbeta and Captain Blanco finally located him. The mayor told them that he had granted the permit, but insisted that he had specifically limited it to a civil demonstration without military character.

Colonel Orbeta tried to show the mayor that the situation was dangerous. He revealed, according to testimony in the possession of the Legislative Committee [a different committee from the one headed by Mr. Hays. ED.] that he had information to the effect that the Nationalists planned to carry arms, and that he knew that an armed group had left Mayaguez to come to Ponce. Later, however, and in the same testimony, Colonel Orbeta, in speaking of this conversation, said that he had told the mayor that a procession of the Nationalist cadets might be disorderly, that he did not know but that somebody might act crazily and throw a stone at a store window or commit some other disorder…

THE PERMIT REVOKED

Colonel Orbeta persuaded the mayor that he would have no trouble with the Nationalists; as Colonel Orbeta said, he was “a persuasive fellow,” and he would tell them that he would try to find a means whereby the Nationalists might have in the future what at the moment “they could not have.”

The mayor, finally convinced by Colonel Orbeta that the parade was a menace to the public peace, agreed to revoke the permit, and he immediately communicated this decision to the Nationalist leaders. When they asked the mayor why he had changed his mind, he answered that he had forgotten that March 21 was Palm Sunday–a religious festival–and that the Paulist Fathers had requested that no parade whatever be held on that day. The Nationalist leaders alleged that they had already made their preparations, that people were already coming from other towns of the island, and that the parade would be not only serious and orderly but also silent. They offered to confer with the Paulist Fathers to persuade them to withdraw their objection. The mayor, however, persisted in his attitude. From that moment on, and until about three in the afternoon, there were conferences in Ponce between Colonel Orbeta, Captain Blanco, and the leaders of the Nationalist Party, who insisted that they would be responsible for the cadets and that there would be no disorder. The conferences ended in thin air. Colonel Orbeta asked them to reconsider. Meanwhile, the police concentrated in large numbers around all the streets that lead to the Nationalist Club, which is situated on the corner of Aurora and Marina Streets. The Nationalists were arriving at the club, bringing their wives, mothers, and children to see the parade. There is evidence to the effect that those who were not Nationalists were kept away from Marina Street, between Aurora and Jobos Streets, and that only Nationalists were permitted to go through police cordons. About eighty of the Nationalists belonged to the cadet organization and arrived in uniform…

WERE THE NATIONALISTS ARMED?

It was alleged that the Nationalists were dangerous. Photographs taken at the moment [before the shooting. ED.] do not reveal a single Nationalist with arms of any kind. This was admitted before the Legislative Committee by police officers. As the Nationalists wore black shirts and white trousers, any concealed weapon would easily have been discovered. It would have been easy for the police to search these men if they had any doubt in regard to the matter…

THE AMBUSH

Not only the military rules brought to light by the testimony but even the most elementary common sense would seem to suggest that ample room should be left for escape.

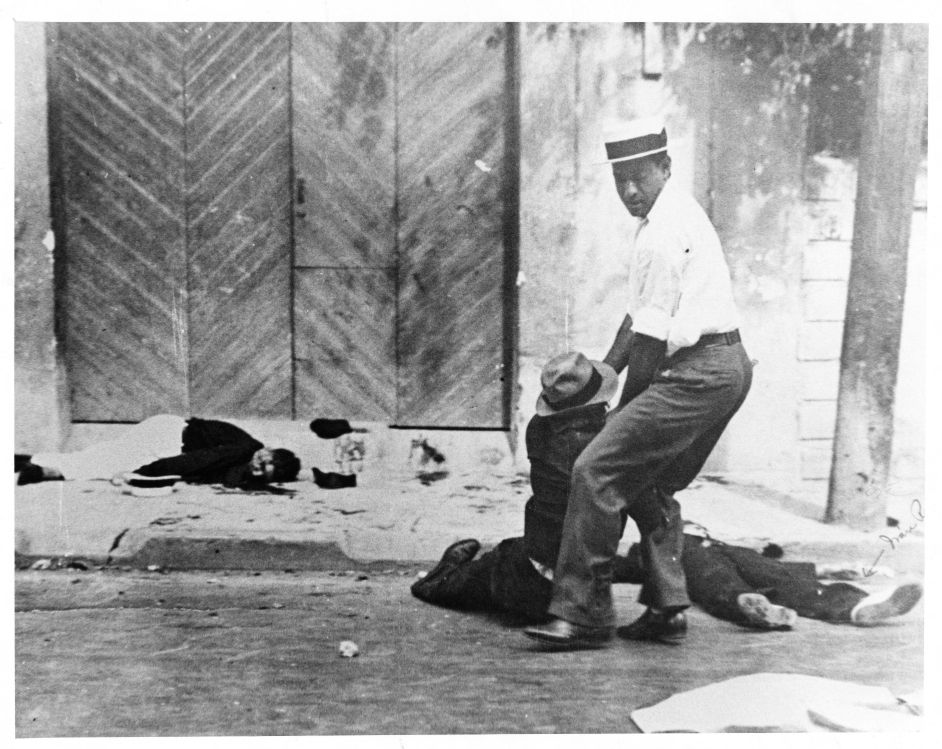

Fortunately we do not have to rely upon verbal testimony. In moments of excitement, the observation of an individual is not completely reliable, and a later declaration, even in the case of the best witness, is likely to be colored by the imagination. Here we can rely upon our own visual sense. Two photographers were on the balcony of the home of the Amy family in order to take pictures of the parade. This house, as will be seen, is next door to the corner of Aurora Street, and the balcony permits a complete view of the scene of the events. The newspapermen took many pictures of the changing scene. One photograph taken by José Luis Conde, of the Mundo, a few seconds before the beginning of the shooting (a copy of which accompanies this report), shows the police in a threatening attitude, closing in on the crowd from the north–that is, from Aurora Street. It shows large groups of people–men, women, and children–on the corner of Marina and Aurora Streets, almost in front of the Nationalist Club. The photograph shows the cadets in formation, then the nurses, and behind these the police contingent with machine guns, under the command of Chief Perez Segarra. We have called attention to the fact that Colonel Orbeta and Captain Blanco, who apparently expected very serious and dangerous developments because of the presumed ferocity of the cadets, had gone to take a stroll around the city. Captain Blanco declared before the Legislative Committee that nobody remained in command of the police force, and that the assistant chiefs Soldevila and Perez Segarra, each with a police contingent under his command, had received no special instructions…

THE FIRST SHOT

A few seconds after the taking of the photograph that has been mentioned, the other photographer, Carlos Torres Morales, photographer of the Imparcial, having observed the threatening attitude and activities of the police, raised his camera to eye-level. Before focusing, a shot was heard, perhaps two–he was not sure. He took the picture [included in the original report. ED.].

In it we see practically all of the policemen on Aurora Street across Marina Street, perhaps seventeen or eighteen men, ready to fire on the crowd. All appear with arms in their hands. One policeman is actually shooting. Although we have adduced the testimony of experts, this was really unnecessary because the policeman who is firing appears with the upper part of his arm extended towards the fleeing crowd. The forearm is hidden by another figure, but in the direction of the upper part of the arm, and beyond the other figure, there appears a white blur due to the explosion of the shot, and still further on appears the smoke of the firearm. The shot is fired directly against the civilians on the sidewalk. The man who is firing can be easily distinguished.

THE MASSACRE

The photograph shows something besides the fact that the police were ready to fire. It shows the police in action. It shows the Nationalist cadets–the Ejército Libertador–about sixty or seventy of them, standing in silence, motionless, with their hands down. In front of the cadets is what appears to be their commanding officer in a white uniform. Following him is a boy in a black shirt with his arm over the shoulder of his comrade. Behind them is the cadet who bears the flag. All the boys look somewhat startled, but are waiting patiently for the disaster. Not one is making a single movement. Behind the cadets appear the girls in their white uniforms, some of them fleeing. One has almost reached the sidewalk. This in itself corroborates the photographer’s statement that the picture was taken after the shooting began. The picture did not include the members of the band, who were behind the girls. Behind the band appear some fifteen policemen, a detachment of sub-machine guns or repeating rifles, all in action, although it is not clear whether they had begun to fire or not…

THE MURDER OF THE LITTLE GIRL

Another witness who appeared before the committee, Jenaro Lugo, messenger of the mayor of Ponce, and member of the Union Republican Party, observed the scene from the balcony of the convent, which, as will be noted from the sketch, is directly in front of the Nationalist Club. He had gone up to this balcony when the police ordered him to withdraw from the street, apparently because he was not a Nationalist. There were also two little girls on the balcony, one of them thirteen years old. This witness had a clear view of the scene. He pointed out the picture of the policeman, who, he said, had fired the first shot. The face is easily distinguishable. The authorities will have no difficulty in bringing out at least enough evidence to try this policeman. Lugo did not remain on the balcony after the shooting began. He ran down the stairs of the balcony towards Marina Street and began to flee in the direction of Aurora Street. As there were policemen stationed at this point, he turned back, in time to see the body of the little girl fall over the railing of the balcony. He saw a policeman approach and riddle her with bullets. The condition of this little girl’s body was so terrifying that, accustomed as Dr. Pila is to horrible scenes, he was nevertheless horrified by the mutilated body that was brought to his clinic. Lugo did not linger after this assassination, but sought refuge behind the walls of Dr. Pila’s clinic. From there he saw the police opening fire on the backs of the defenseless crowd with sub-machine guns or Thompson repeating rifles…

THE MURDER OF THE RODRIGUEZ FAMILY

We have mentioned the fact that members of the Rodriguez family, the father and three sons, had come from Mayaguez by automobile, and having parked it towards the south of Jobos Street, they got out and took places so as to watch the parade, in front of a shoe-repair shop on the south side of the building in which the Nationalist club is located. Rafael Rodriguez, eighteen years old, had calmly taken some pictures with his camera and was about to take some more. They had hardly reached the sidewalk when they heard shots. The father and two of the sons immediately threw themselves to the ground, face down–Rafael with his face towards the south, his feet towards the north, and his right hand stretched out towards the sidewalk. There was a volley. He heard his brother shout, “Ay!” and the father, apparently recognizing the last word of his son, rose to throw himself over the body of his wounded son in order to protect him. As the father rose, Rafael saw that his head was covered with blood. He was mortally wounded. Rafael stayed where he was for fifteen minutes, wounded in the right arm. From there he was roughly raised by a policeman who threw him into a police wagon…

THE MURDER OF THE GUARDSMAN

There were others in the wagon. Among them a young man, brutally wounded, was taken to the police wagon and thrown against the seat. He was bleeding from his nose, his mouth, and other parts of his body. All that Rafael could hear when the man tried to breathe was his halting and plaintive cry: “I am a National Guardsman. I am a National Guardsman.” He repeated this over and over again until death silenced him. The evidence shows that this member of the National Guard was not in the parade but that he was going home by way of Aurora Street. A blood-thirsty policeman fired at him. He shouted, “I am not a Nationalist. I belong to the National Guard.” The policeman kept on firing until the boy fell to the ground. Even then the policeman kept on firing.

MORE ON THE RODRIGUEZ MURDER

But there is another, more atrocious story about the Rodriguez family. It is to be noted that from somewhere-the source of information is not difficult to guess there arose a rumor that a civilian had fired the first shot. Perez Marchand identifies for us the civilian under suspicion. He was a man, says Marchand, who had a son among the Nationalists. The story was that, fearful that the police might wound his son, the father fired at the police. Why he did such a thing, if his purpose was to protect his son, is beyond our comprehension. But that is the story. This story was corroborated by four different witnesses. But the father of Rafael was dead so that he could neither deny the story nor defend his reputation. The boy declared on the witness stand: “I am interested in the truth in order to vindicate my father. I want the truth to be told in the newspapers, not only in Puerto Rico but also in the United States, so that everybody may know that my father was an honorable man and a gentleman.” Other facts demonstrate conclusively that Mr. Rodriguez met his death while he was amusing himself in what ordinarily constitutes an innocent pastime–he was watching a parade pass by. In the first place, the photo shows that Rodriguez was in the center of a group of civilians, and that a dense group of men separated him from the police. Nevertheless, it is said that the first shot came from this man. Then there is the curious fact that the man who fired the first shot was killed, but that, nevertheless, no gun was found anywhere near him on the street; as a matter of fact, no gun was found anywhere in any of the streets…

THE MURDERS OF THE MAYAGUEZOS

Other witnesses from Mayaguez relate horrifying stories. Julio de Santiago was a leader of the Mayaguez Junta. He took his wife to the parade. He found himself in front of the Nationalist Club when the firing began. The pressure of the crowd trying to take refuge within the club threw him to the ground. Inside there was terrible confusion, with wounded stretched everywhere. There were no bandages; there were no women to give first aid; the men did the best they could. They used their shirts as bandages. A long time passed before any ambulance arrived. The doors of the club had been closed because they feared a mass assassination. Trying to get help for a wounded and apparently dying woman, they opened the door and waved a white handkerchief as a banner of peace. They were answered with a volley. The door was closed. The marks of the volley appear on the building.

Of the people who came from Mayaguez, four men were killed, of whom two were young cadets. There were six wounded. In the parade there were six girls from Mayaguez wearing nurses’ uniforms. One of them was wounded. The director of the nurses’ group was Dominga Cruz de Becerril. She told her story calmly but firmly. The police with Thompson rifles, when they began shooting, were behind the nurses. The girls began to run. One of them was wounded. Dominga went immediately to help her, a young cadet approached. Dominga noted then that the flag-bearer of the girls’ group had fallen. She went to the middle of the street and raised the banner. We asked her why. She answered simply: “My master has said that the banner should always be kept raised.” The “master” is Pedro Albizu Campos, now in prison, convicted of conspiracy to overthrow the government of the U.S. One cannot avoid feeling humble before such heroism…

WAS THERE FIRING FROM THE ROOFS?

It has been said that there was shooting from the rooftops. We shall refer to this later on. It is enough to say that not one of the witnesses who testified before this committee said that he had seen anybody on the roofs. All the houses in the immediate vicinity of the tragedy are inhabited by people of high standing. The fact that it was said that there had been firing from the roofs made Mr. Sanchez Frasqueri so indignant that he decided to testify against the police from the very beginning of the investigations. Mr. Sanchez Frasqueri is one of the citizens of best reputation and greatest distinction in Ponce. He denied the calumny that had been raised against that reputable neighborhood. He lives in the eastern part of Marina Street, between Luna and Aurora Streets. On Palm Sunday he went to a social center on the other side of the street and was amusing himself at a card game with three friends of his. Suddenly they heard shots. The first shot sounded like the explosions from a starting motorcycle. When this detonation was repeated, all ran to a balcony of the house from which they could see Luna Street. As they could see nothing on that street, they ran to the other balcony, some sixty yards away, from which Marina Street was visible. When they reached the other balcony, the volleys had already ceased, and in spite of this, according to the declaration of the witness, there were shots at intermittent intervals for about half an hour. As soon as Sanchez Frasqueri looked out from the other balcony, he saw a man who was lying in the street and trying to raise himself. The first impression had been that he was a dead man, but when the man lay down again, it became clear that he had thrown himself to the ground to save himself from the bullets. Two policemen approached this man who was lying on the ground, as though to attack. At this moment, Mr. Sanchez Frasqueri shouted to them, “Don’t kill him!” One of the chiefs of police came up when he realized that Sanchez Frasqueri was looking on. The chief ordered the men to abandon their intention. The next time that Sanchez Frasqueri saw this same man (he found out later that he was a painter), the man had a bandage around his head. This man told Sanchez Frasqueri that he had been put into a police ambulance and that there the police had clubbed him over the head.

While Sanchez Frasqueri was on the balcony, he received a telephone call from his house on the other side of the street. His son told him that his home was full of women, children, and others who had sought refuge there, and he asked his father what he should do. Sanchez Frasqueri went to his home. When he entered, he realized that the house was full of tear gas, or of odors that apparently were of that kind of gas. The people who were in the home of Sanchez Frasqueri were filled with panic. Some of them wanted to leave immediately for fear that the police would catch them there as though in a rat-trap.

On Marina Street, between Luna and Aurora Streets, Mr. Sanchez Frasqueri saw a corpse on the ground that remained there until two civilians approached and raised it to carry it to the hospital. Near the corner of Luna Street (seventy-five yards from the Nationalist Club where the cadets had formed their ranks) Mr. Sanchez Frasqueri observed the mutilated body of a man already dead who had written in blood on the wall of a building and who, while dying, continued to write the word “valiant” (valiente). This person got only as far as the first three letters “v-a-l,” and then he fell…

WERE THE NATIONALISTS RESPONSIBLE?

What is the basis for the assertion that the Nationalists were responsible for the killing? It is said that a civilian fired a shot. This has already been answered. It is said that some men fired from the roofs. The evidence received by this committee is against this assumption. Mr. Francisco Parra Capo, outstanding lawyer and leader of the Union Republican Party, referring to this, said: “The police saw Nationalists even in the clouds. I know the neighborhood. It is unjust to say that the people who live there either fired or permitted firing from their homes.” Another resident of Ponce, Dr. de la Pila Iglesias,

when asked if he feared to attend a Nationalist parade, answered, “Of course not.” And when asked if he would be afraid to attend one if the police were there, he said, “That’s different. I would fear for my life.”

It was said by the police that there were arms in the Nationalist Club. The police were firing in front, behind, and on the right and left sides; in reality one of the chiefs of police declared before the Legislative Committee that he had become crazed from the effects of the gases of the tear-gas bombs and that he found himself in the convergence of the four lines of fire. From the proof it appears that two policemen were killed and some six wounded. It is strange that there were no more dead or wounded policemen.

GOVERNOR WINSHIP’S REPORT

On March 22 the governor of Puerto Rico rendered a report to the secretary of the interior of the U.S. which reads as follows:

“I am profoundly moved by the events that occurred yesterday in Ponce. From the information that I have received as the result of investigations carried out by judges, district attorneys, and other government officials in Ponce, as well as from information derived from other trustworthy sources, the following are deduced to be the facts of the case:

“Several days ago, it was announced in the papers of the country that on Sunday, March 21, 1937, there would be held in Ponce a concentration of the divisions of the so-called “Ejército Libertador” of the Nationalist Party. The announcement in question was written in the form of a military order. The chief of the Insular Police went to Ponce last Friday, March 19, and conferred with various prominent citizens and with the local chief of police. All those who participated in this conference were of the opinion that the concentration and parade announced, if they were permitted, would possibly bring as a result disorders and bloodshed. Later on, during the course of the day, the insular chief of police [Colonel Orbeta. ED.] held a conference with me, and it was decided, in view of these allegations, that it was in the interests of public order that the concentration and parade planned by the Nationalists should not be permitted. The next day the chief of police of Ponce informed the insular chief of police here that he had been notified by the Nationalists that they proposed to hold the concentration and parade on Sunday, March 21.

“On said day the chief of the Insular Police went again to Ponce, where he received information to the effect that the mayor of the city had authorized the holding of the concentration and the parade, but after he had exchanged views with the mayor and they had carefully considered the circumstances, the mayor decided to annul the permit that had been granted, which was done immediately in writing. In view of this situation police reserves were sent to Ponce from several points of the island. Soon after noon of March 21, a group of Nationalists, most of them wearing the uniform of the “Ejército Libertador,” appeared in formation before the headquarters of their party. Also there were men posted on the roofs and balconies overlooking the highway. Two of the Nationalist leaders, Graciani and Quesada, asked for an interview with the chief of the Insular Police in police headquarters in Ponce. The interview took place, and the chief of police explained carefully to them the gravity of the situation and the serious possibilities inherent in the same. He told them that a parade of a civil nature could be held at any time in the future so long as it was not of the divisions of the so-called “Ejercito Libertador.” The two Nationalist leaders were apparently convinced of the dangers involved in a parade through the streets of Ponce. The chief of the Insular Police went to the extreme of offering to appear personally to explain to the assembled Nationalists the seriousness of the situation, and he waited more than half an hour in his office in order to determine whether his suggestions had been favorably received. However, he got no news from the Nationalists.

“At 3:30 p.m. the band of the Nationalists played the “Borinqueña,” at the end of which the command of “forward” was given by the head of the column of Nationalists, thus showing that they were determined to carry out their plan of holding a parade. The local chief of police warned them then in a loud voice that the parade was forbidden. Immediately two shots were fired by the Nationalists, the first wounding a policeman who was at the left of the chief, and the second the policeman who was at the right of the chief. A general exchange of shots occurred then between the Nationalists and the police, many of which were fired by the Nationalists, and also from the street, from the roofs and balconies on both sides of the street. The shooting lasted about ten minutes until the chief of the Insular Police arrived at the place of the events and helped to restore order. The casualties amounted to ten killed [others died later of wounds. ED.] and fifty-eight wounded, including one policeman killed and seven wounded.

“Later on the police entered and searched the Nationalist headquarters, in front of which the column had formed. Inside said headquarters, the police found dead and wounded Nationalists, pistols, revolvers, and munitions. There was also taken a secret order of the local Nationalist leader in which he gave specific instructions to the members of the so-called “Ejercito Libertador” to come to the city of Ponce dressed as civilians and telling them that they should don their uniforms in private houses before coming, individually, to the Nationalist headquarters, taking care not to appear publicly in groups.

“The civ authorities, immediately after the occurrence of these lamentable happenings, began their investigations, and I have given specific instructions that these be carried on with speed and energy. A number of arrests have been made. I have the firm conviction that during the two visits made by the Insular Police chief to Ponce, he employed every means of persuasion to point out the possible dangers involved in the parade, and to dissuade the leaders from their insistence in carrying out their plans, with the purpose of avoiding a conflict. The preliminary investigation that has been carried out seems to show that both he and the officers and men under his command showed great patience, consideration, and understanding in dealing with the situation. BLANTON WINSHIP, Governor.”

THE COMMITTEE REPLIES

It should be noted that in this report the governor talks of investigations by “judges, district attorneys, and other officials of Ponce,” and of “other trustworthy sources.” The testimony before us does not show that a report was submitted by any judge. If such a report was made, the judge certainly was not very active in the investigation. The “other officials” of Ponce we have been unable to find. The official investigation was made by the district attorney, the attorney in office at that time. We don’t know either what is comprehended in the term “and other trustworthy sources,” unless it refers to Colonel Orbeta and Chief Blanco, neither of whom was present when the events took place. The district attorney of Ponce at that time was Rafael V. Perez Marchand. The first report of Perez Marchand to the governor was the only one at hand when the above-mentioned message was sent…Perez Marchand appeared before this committee and declared that he was district attorney of Ponce on March 21, 1937, and that he had served in that capacity for four years. The first news he had of the massacre (in the future we shall use this appropriate designation) was rather late in the afternoon. The massacre occurred between three and four o’clock in the afternoon. It is true that Perez Marchand was at his country home, but this was only ten minutes away, and it was known where he was. Nobody in the Police Department notified him of the affair until about six o’clock in the afternoon, when Orbeta’s car with policemen in it arrived at his house. He was told that “something terrible had happened.”

He was told that the Nationalists had fired at the police, that a general exchange of shots from both sides had taken place, and that police, Nationalists, and others had been killed. The policeman who occupied Orbeta’s car still carried his Thompson gun. Perez Marchand asked him, “Have you killed anybody?” The reply was, “I hope to God I haven’t, but I don’t know.” Perez Marchand smelled the fire-arm, from which there came a penetrating odor of recently burned powder.

CONFIDENTIAL DOCUMENT

On March 22, the day before the governor’s radio broadcast, Perez Marchand rendered a report to the governor. In the hearing he told us that he did not feel at liberty to show it to us, since he felt that it might be regarded as a confidential document. Still another report was made by Perez Marchand on March 24, but the same considerations applied to this as to the former one. A third report was rendered on April 2. This report was published by the press. It was submitted to the committee. It did not bear out the story as told by the governor. Then we communicated with the attorney general. We asked him to relieve Perez Marchand of any obligation of secrecy if there was any, so that we might see those other reports, the first of which we assumed must have been used as an adequate basis for any report of the governor to the secretary of the interior. We called the attention of the attorney general to the fact that although Perez Marchand had given all the testimony that he could, there was further evidence to which we thought we had a right. Perez Marchand was not relieved of his obligation. The attorney general, when he appeared before this committee, said that he would consider the matter.

THE COMMITTEE INSISTS

On May 19, 1937, the chairman of the committee telegraphed to Perez Marchand as follows: “The attorney general answered our petition that you be relieved of obligation of keeping secret the confidential testimony, that his answer was unnecessary since you had already testified. We have been unable to obtain any other answer from him, although we informed him that you had kept back considerable information. Since the governor made a report that he said was based largely on yours, and since he made public that report, don’t you think that this relieves you of your obligation and that it is your duty as a citizen to reveal the facts? If you agree that this is so, could you come to San Juan tonight and testify as our last witness? (Signed) Arthur Garfield Hays.”

In answer, the following telegram was received from Perez Marchand:

“I am so incapacitated by a bronchial infection that I feel unable to travel in order to submit additional evidence before your committee; but considering the recent testimony of the attorney general and the report of the governor, I accede to your telegraphic request, and remit a certified copy by special delivery of my first and second reports on the Ponce massacre, until now retained by me, so that you may confirm the fact that I never informed the Department of Justice that a Nationalist had fired the first shot, and what more, that I never reported that hidden shooters fired at the police from the roofs or buildings as a certain authority reported to Washington. Later, I was confronted with the alternative of maintaining constitutional liberties and truth at the cost of a slight sacrifice or of gaining personal advantages at the price of my concept of civic duties, and I did not hesitate to resign my position in order to be in accord with liberty and the constitution.”

It is unnecessary to state that the reports which Perez Marchand rendered then and which we have copied above [in the full text of the original. ED.] do not in any way sustain the data in the governor’s report.

The third report says that there was some evidence to the effect that a citizen had fired the first shot.

1. But no statement was made to the effect that a Nationalist had fired. Reference has been made to the unfounded accusation against Rodriguez, Sr., who was killed. Perez Marchand said that he was under the impression that the son who was killed was a Nationalist. But the evidence shows that neither were Nationalists.

2. After saying that the Nationalist band played the “Borinqueña” and a march, and that at the end, the order of “forward” was given by a Nationalist leader, the governor’s report continues to say that the “local chief of police announced that the parade was forbidden.” As a matter of fact, the local chief was Captain Blanco, and he was not there, but we will overlook this, since the governor may have been thinking about a chief of police of some other town. The error was probably due to a confusion between officers; we don’t know exactly. But it appears strange that no mention is made of the fact that both the local chief and the colonel of the Insular Police were absent and that there was nobody in command.

A FALSEHOOD EXPLODED

3. The governor’s report says: “Immediately two shots were fired by the Nationalists, the first hit a policeman who was standing at the left of the chief and the second a policeman who was on the right of the chief.” This is not only false as a matter of fact, but also there is nothing in the report of Perez Marchand that can be interpreted in that way. In the first place, there is here the same confusion about the “local chief of police” that we have noted before. In the second place, there was never any information from the district attorney to the effect that the first shot was fired by a Nationalist. Perez Marchand never went further than to say that there was some evidence to the effect that a citizen might have fired the first shot.

It is also false that the first shot hit a policeman who was standing to the left of the chief. This is shown by the photograph mentioned above [Exhibit 2 of the committee’s report. ED.] Since the message or report says that the first shot was fired by a citizen, it is obvious that the shot seen in the photograph is not the first shot (if the report is exact). So that if what the governor says is true, it is logical to expect to see a policeman on the ground, for according to this statement, the first shot hit a policeman standing to the left of the chief. But the photograph not only shows that no policeman had fallen, but on the contrary, shows that all are standing and in action. Chief Soldevila, who was in charge of the forces at the spot of the first shooting, is, as the photograph shows, in the foreground of the same. There is no policeman directly on his left. The closest to his left is several paces away, and his perfect state of health is demonstrated by his military posture of attack.

A like observation applies to the second shot which it was alleged (by the governor) had killed another policeman standing at the right of the chief. As a matter of fact, the man who appears to the right of the chief is the Nationalist leader. Not only are there not two fallen policemen on the ground, but there isn’t even one. The photo shows beyond contradiction that at the moment when the police were firing (the photo shows the police firing), no policeman had been hit by a shot, unless in this big police reunion which is seen in the photo, in which all are drawing their guns and are about to fire, there are two heroes who, in spite of having been shot, remain standing without showing any sign of it either by vacillation or by any sort of gesture.

THE ROOF MYTH

4. The report of the governor continues: “Then there occurred between the Nationalists and the police a general exchange of shots, with the Nationalists firing from the streets. This shooting lasted ten minutes. There were also men stationed on the roofs and balconies overlooking the street.” As a matter of fact, there was nobody on any roof, and there were no shots from any roof or balcony. Perez Marchand said in his telegram that he had never reported that. Neither is there any reference to this in his reports which we are fortunate enough to have before us now. Only two of the houses of the neighborhood have terraces on the roofs. There is no witness who has seen anyone on any roof.

The photographers who were taking pictures for their papers took careful note. The only people on the balconies, so far as we have discovered, were onlookers who were among our witnesses. These observers include Sanchez Frasqueri, who was on the eastern side of the street on a balcony some 150 feet away and who had a complete view of the scene; José Luis Conde and Torres Morales, the photographers, who were on the balcony of Mr. Amy’s house just above the scene of the events and not more than forty feet away; Janaro Lugo, who was on the convent balcony just opposite the Nationalist Club near which the shooting began; Julio Conesa, who was on the balcony of the Protestant church building almost directly above the contingent of Perez Segarra with their machine-guns. If the public officials had placed observers before the events in places suitable for seeing what happened on Marina Street, from Luna Street to Jobos Street, they couldn’t have found better positions. All these men (the eye-witnesses) are respected citizens, totally disinterested, and none of them are Nationalists. Very few of them were called by the authorities to testify in the inquiry concerning the affair.

ANOTHER LIE

5. The report to the secretary of the interior says also: “After this the police searched the Nationalist Club, in front of which the column was formed, and there they found a number of dead and wounded Nationalists, revolvers, pistols, munitions, etc.” This is true only in part. The police found a number of wounded and dead Nationalists, but they found no pistols, revolvers, or munitions.

It is said that the police took six or seven pistols. The Nationalists whom we questioned and who were in the headquarters (office of the Nationalist Club) before and after the events told us that there were no pistols. When the committee questioned Lorenzo Piñero, one of the Nationalist leaders, about how it was possible that the police had found the pistols, he answered as follows: “I am surprised that they didn’t find tanks and machine guns, too.” Fortunately, we had the advantage of obtaining evidence from irreproachable witnesses in regard to this fact. Two lawyers of Ponce, Ramos Antonini and Gutierrez Franqui, had been standing on the southeast corner of Aurora and Marina Streets waiting for the parade to begin. While they were talking, they met there a friend, Mr. Guillermo Vivas Valdivieso, editor of the Dia of Ponce. This friend informed them that he had been eating with Colonel Orbeta. On the witness stand, he said: “When the Nationalists gave the order of ‘march!’ I was there in those very moments; I had somebody who protected me. If I had stayed there, perhaps I would not be here to testify.” The witness added: “I wish to add as a citizen who loves and respects order, that the attitude of the Insular Police towards a city that has always conducted itself with great order and respect was very much the contrary of what I think it should have been.”

THE FRAME-UP

At any rate, Mr. Gutierrez Franqui and Ramos Antonini remained on the corner after the shooting had begun. Then they sought shelter on the north side of Aurora Street. Mr. Gutierrez Franqui testified about the shooting by the police. When the excitement had died down, he and Ramos Antonini came out of their respective places of refuge. They met Colonel Orbeta, who was now on the scene. Orbeta said that he was going to search for arms, and he asked these two men as public-spirited citizens (in the absence of public officers) if they were willing to come with him in order to certify the good faith of the search. These men joined Colonel Orbeta. When they entered the Nationalist Club, they saw a policeman with a revolver approach them and heard him say, “Chief, look what I found.” Then they entered and saw that a minute search was being made which included even the tank of the water closet. It is reasonable to suppose that the pistols were not in the building and were not found there. Moreover, one may very well ask: if the Nationalists proposed to do harm by force of arms, why and for what earthly purpose would they have left their pistols inside the Nationalist Club?

This committee maintains the unanimous opinion that the Nationalist cadets at no time had pistols either on their persons or in the club at Ponce and that this statement in the report to the Department of the Interior lacks any basis in fact.

On the other hand, it is necessary to recognize the fact that the one who drew up that report received information from Perez Marchand to the effect that the police had taken six or seven firearms.

6. The report continues, stating that a secret proclamation of the local Nationalist leader was found “giving specific instructions to the members of the so-called ‘Ejército Libertador’ to report to Ponce without uniform and to don their uniforms in private houses, and then to report one by one to the Nationalist Club, taking care not to appear publicly in groups.” It is difficult to conceive why such an order had to be secret, or why anybody should believe that the Nationalists would gain anything by putting on their uniforms elsewhere than in their own homes. When the Mayaguez group, to be specific, left their hometown, quite distant from Ponce, those who were cadets were wearing their uniforms.

CONCLUSION

7. The report to the secretary of the interior says: “From the preliminary investigations it is evident that he (referring to the chief of the Insular Police) showed great patience, consideration, and understanding, as did also the officers and men under his command.”

8. These statements in the report praising the chief of police as well as his officers and men are the most objectionable error of all those made in the message. Instead of showing “patience, consideration, and understanding in dealing with the situation,” the chief of the Insular Police and the local chief of police were not there when they were needed, and there was nobody in command.

Instead of patience, consideration, and understanding on the part of the other chiefs (besides the two who were absent) and on the part of the men, the words necessary to describe their conduct would be lack of consideration, blind blood-thirstiness, and vicious destruction of lives.

And it is opportune to point out that, nevertheless, the people of Puerto Rico considered the police, before it was militarized, as a courteous and friendly organization.

The New Masses was the continuation of Workers Monthly which began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Communist Party publication, but drawing in a wide range of contributors and sympathizers. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and The New Masses began. A major left cultural magazine of the late 1920s and early 1940s, the early editors of The New Masses included Hugo Gellert, John F. Sloan, Max Eastman, Mike Gold, and Joseph Freeman. Writers included William Carlos Williams, Theodore Dreiser, John Dos Passos, Upton Sinclair, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, Dorothy Parker, Dorothy Day, John Breecher, Langston Hughes, Eugene O’Neill, Rex Stout and Ernest Hemingway. Artists included Hugo Gellert, Stuart Davis, Boardman Robinson, Wanda Gag, William Gropper and Otto Soglow. Over time, the New Masses became narrower politically and the articles more commentary than comment. However, particularly in it first years, New Masses was the epitome of the era’s finest revolutionary cultural and artistic traditions.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/new-masses/1937/v23n11-jun-08-1937-NM.pdf