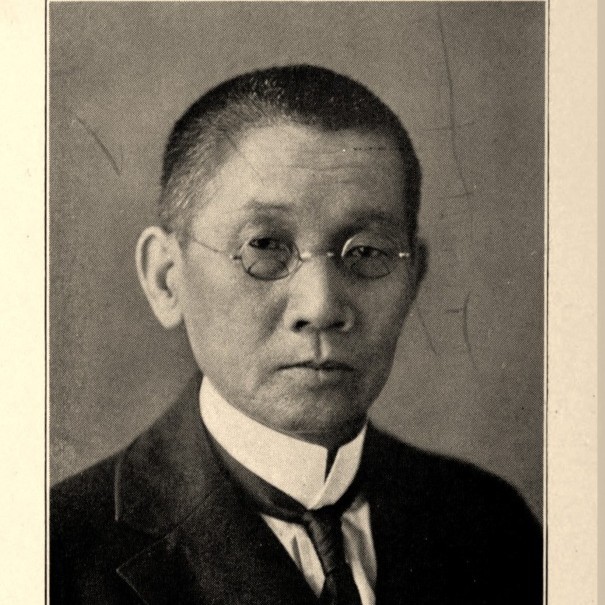

Katayama on the terrific expansion of Japanese capitalism under state sponsorship and as a growing imperialist power to the First World War.

‘Recent Development of Capitalism in Japan’ by Sen Katayama from Class Struggle. Vol. 1 No. 3. September-October, 1917.

Japan is a snug home of modern capitalism. The government of Japan has been very eager to make it so. It helped capitalism to grow, politically and financially, in every possible manner. Originally the government of modern Japan was established by the desperate efforts of the lower ranks of samurai (the hereditary soldiers in feudal Japan), mostly of two clans—Chosiu and Sassiu. When they established the revolutionary government in 1868, after successfully overturning the feudal government at Yedo, now Tokyo, they repealed all laws of the feudal regime, declared freedom of occupation and of movement, and confiscated the land of the feudal lords (36), together with those of their chief—Tokugawa Dynasty. Thus the new government took away legal monopolies that were formerly conferred on private persons by the feudal government. All castes were said to be abolished and religious restrictions were done away with. It gave tenant farmers of feudal lords a full legal title to all the land they cultivated or used, without payment. The thus newly created land owner had only to pay a tax of 3 per cent, on the land value. The valuation of the land all over the country was based on the productive income of rice crop. Rice cost then $1.75 a koku (1 koku is 4.9629 bushels). In this way the new revolutionary government obtained the confidence of the farmers. The government, moreover, promised the farmers that the land tax of 3 per cent, would soon be reduced to 1 per cent, a promise which was, however, never fulfilled. But the land owners have profited by the natural increase of land values and the increased incomes from the yield of land as a result of the general progress of the country.

Until the revolution of 1868 the farmers had been paying, in a form of rent in rice, 85 per cent, of the entire national expenses, but to-day the land owners pay only slightly over 12 per cent, of the national budget, although they have been getting larger rice crops. From 24,449,000 koku in 1877 it increased gradually to 58,301,000 koku in 1916, while the price of rice increased in the same period from $2.75 to $10.00, an increase of 267 per cent. This being the case, farm lands have been rapidly capitalized and the price of land has been rising by leaps and bounds. An acre of paddy field costs as high US $3,000. As a result small farmers are being driven into a corner, to sink once more into the class of tenant farmers, under the increasing exploitation of the capitalist land owners. The thirst for land is largely attributable to valuable political rights and privileges bestowed on the land owners.

In 1890 the imperial constitution was promulgated and the national parliament was opened in the same year. The constitution has many inviting provisions, such as freedom of press, thought and assembly, but conditioned by a clause—according to the law or within the law. It gives, however, to the Japanese capitalist class a practical monopoly of political rights and privileges upon which the firm foundation of Japanese capitalism is laid. Parliamentary suffrage rights are restricted by property and educational qualifications, thus practically limiting the franchise to the big land owners and capitalists.

With a population of sixty-five millions, there are in Japan only a million and a half voters. It follows that the two branches of the parliament are completely bourgeois. The lower house is dominated by the land owners and capitalists, the upper house is controlled by hereditary nobles and specially appointed bureaucrats, all conservative and reactionary. Both houses are the faithful servants of bureaucracy and capitalism, so that the ever-increasing national budget has been shifted always onto the shoulders of the working population ($40,000,000 in 1893 and $301,000,000 in 1917) by means of indirect taxes. At present nearly two-thirds of the national budget is raised by indirect taxes. In every conceivable way favoritism in legislation has been bestowed upon the rich people, at the expense of the vast toiling masses. The transportation tax is a particularly flagrant example of this fact. There is a tax on one sen (1/2c) on street car tickets bought singly. If, however, they are bought 100 at a time, an expenditure out of the question for the poor, there is a tax of but 5 sen (2 1/2c) on the whole. And in the government railroad, discrimination in favor of the rich is still more marked. There is a tax of one sen on every ticket up to 50 miles for every local trip on the railway, electric or steam. But if you buy the same distance in a season ticket of six months or one year you pay only 5 sen as a tax for the whole season. The tickets may cost $25, $30 or $50, but the tax is only 2 1/2c.

Japan has, at present, a national debt of one and a quarter billion dollars, paying interest at 4 and 5 per cent. The government pays annually about sixty million dollars interest on those bonds. The incomes derived from the government bonds are entirely exempted from income taxes, but a worker or a clerk who gets $20 a month is required to pay a national income tax which amounts to somewhere near $4.00 or more a year, besides innumerable local taxes. And yet he has no voice in national elections.

Salt is a government monopoly. It was inaugurated with two purposes in view—to get an increased revenue for the government and to protect the owners of the salt fields in the four main islands of Japan. The government gets 74c on every 100 pounds of salt sold; at present the wholesale price of 100 pounds is $1.25. But if the government gets it from Formosa, where the salt supply is unlimited, it may get 100 pounds of salt at 15c to 20c, while salt may be imported from Manchuria even more cheaply. But the government limits production of Formosan salt to just enough to meet the deficit in the supply produced upon the main islands. This uneconomic policy is obviously for the protection of salt farmers or old salt field owners, whose properties were valued at two or three million dollars before the salt monopoly was enforced. To-day they are worth from ten to fifteen million dollars. Thus, the common people have to pay more for salt. State capitalism in Japan is maintained for the interest of private capitalists. Growth of capitalism in Japan has been even greater under such favorable conditions. To this end all the welfare and happiness of the common people and workers is sacrificed. From the beginning of the present era Japan helped its capitalists in every way. It has been the policy of the government to start new industries on a capital of taxes, to sell them at a very nominal figure or even to turn them over gratis into the hands of some capitalist high in government favor. Furthermore, very rich subsidies and bonuses are given to many capitalist enterprises without limitations. For instance, in order to build up a cotton industry in Japan, the government made the cotton free of import duty. This, of course, killed the home cotton growing industry, which until then had clothed the entire population of thirty-five millions The cotton industry is now one of the biggest industries in Japan, working 2,870,000 spindles, importing cotton valued at $110,000,000 a year. The industry is controlled by big capitalists under the management of 161 companies. There are over 400,000 women workers in the cotton and other textile industries; these poor girls, mostly under 20, some of them 10 or 12 years of age, are mercilessly exploited in the factories. Female cotton spinners work 12 hours a day for 28 or 29 days every month. Half of them are employed at night, for, according to the new factory statutes it has become legal to employ children of 10 for 14 hours a day. These statutes are to be in force for the next fourteen years.

Girls are forced, as a consequence, to leave the factories after a very short time, broken down from overwork and the ravages of infectious diseases. It has become necessary to recruit, annually, a supply of eight hundred to a thousand new girls in some of the larger factories in order to keep up the necessary supply of female labor.

Every year some two hundred thousand girls are newly recruited to supply the factories; of these a few stay more than a year in the factory, eighty thousand return, the rest disappear. Upon such a brutal exploitation system the cotton masters have built up their industry in a short time, capitalized at nearly a hundred million dollars and producing some four hundred million dollars’ worth of cotton yarn and goods a year.

But the most extravagantly protected industry in Japan is the Formosan sugar industry. Japan took the island in 1898. Since then the government and its capitalists have decided to raise the sugar supply for the entire country in Formosa, and proceeded to establish sugar companies under very high protection. In the early stage of the industry the government supplied, freely, seeds, machines for cultivation and refinery, and many other aids. To keep up, or rather, to raise sugar prices the government put up very high protective customs duties on sugar and passed a sugar consumption tax to be used for the payment of direct bounties to the sugar companies. At one time 80 or 90 per cent, of the cost of production was paid to the sugar masters in Formosa either directly or indirectly. Furthermore, the government gives a direct bounty of 50c on every hundred pounds of sugar cane raised. The sugar industry in Formosa is capitalized on a gigantic scale. In a little while its valuation has reached forty-two million dollars and it produced 517,520,000 pounds in 1912 and 681,179,000 pounds in 1917.

Nor is this all. When a group of capitalists start in the production of sugar they buy sugar lands from poor natives at very low prices. The purchase amounts, practically, to the confiscation of the desired lands from the farmers. The lands thus obtained are then tenanted at very high rentals. In this manner the natives are exploited, powerless and rightless, as a conquered people.

At present there are eight or nine sugar companies in Formosa, monopolizing practically the whole sugar territories. This division of the sugar territories is intended to regulate the production of sugar and the price of cane. Each company has a fixed sphere of influence within which this company buys the cane at its own price. The farmers cannot sell to others, so they are the easy prey of the sugar masters. Thus the Formosan sugar industry is built up for the sole interest of certain capitalists at the expense of the people and the natives. The sugar masters, moreover, are combined to sell sugar, in conjunction with the capitalist sugar dealers of the country, and regulate the home supply. Thus they keep up the prices artificially throughout the year. Before the war the Japanese had been paying more than double the price that was paid for sugar in America. The surplus product is dumped into China and into other markets at less than cost price. This present year they have agreed among themselves to export 3,289,216 piculs, in order to keep up the prices at home at the present abnormal level. This is a typical illustration of the Japanese system of protection for capitalist industries. These sugar capitalists who have been making a vast profit every year by means of legal protection would crash into hopeless bankruptcy if they should be deprived of this protection. They live on government protection at the expense of the people.

In much the same way every big industry is protected by an elaborate legislative scheme. Thus, for instance, all big banks are, in one way or another, protected by special privileges. Yokohama Specie, Kangyo, Kogyo Banks and the Bank of Japan all have legal monopolies by means of which they exploit the people. The Kangyo Bank has the right to gather small funds by means of a lottery. The Kogyo Bank has been empowered to take a commission of $1 on each $100 on all imported capital.

There is perhaps no nation on the face of the earth that so generously and so bounteously protects capitalism and its interests as Japan. Indeed, it is the government of the capitalists, by the capitalists, and for the capitalists.

Again, the shipping trade and the ship-building industry are both subsidized for many years. For the last fiscal year the ship-building trades received an aggregate sum of one and one-half million dollars, while the shipping industry drew several millions from the public coffers. The biggest of these companies is the N.Y.K., with a paid-up capital of twenty millions and a reserve fund equally large. This company alone, which paid a dividend of 70 per cent, last year, nevertheless received some one and a half million in subsidies.

Thus modern capitalism in Japan is well protected and aided on the one hand, and tolerated, or rather encouraged, by the government in its exploitation of the workers on the other. To keep the working class in subjection to their greedy and brutal capitalist employers, the government has always put down every form of labor and socialist organization with an iron hand.

In the 90’s the former had become comparatively prosperous. To-day there is no labor organization by means of which the workers may resist the brutal exploitation of their master class. Obviously legal protection and favoritism from the government are of little value to the capitalist, unless coupled with the power and the freedom to exploit his workers. And to this end the Japanese government has zealously suppressed the socialist and labor movements from their very beginning.

The so-called factory laws that were passed in 1911, to go into effect in 1916, are, as a matter of fact, in no sense a protection for labor. Under their provisions women and children are permitted to work 12 hours out of 24. Furthermore, for a period of 15 years after the enactment of the law, the work-day may be extended, if necessary, to 14 hours. The family of a worker killed in a factory receives a sum equal to the wages of 170 days. If he is crippled for life while at work he may receive a compensation equal to the wages of from 30 to 170 days altogether. Yet this is the only labor protection law in Japan.

Since the beginning of the European war, Japanese capitalists have been making enormous profits. Factories are running to their utmost capacity. It has been called the Golden Age for Japanese. labor. What this really signifies is rather doubtful. An investigation conducted by the Osaka Chamber of Commerce discloses clearly that this prosperity cry in Japan, as everywhere the world over, is a sham and a delusion of capitalist origin. Out of 75 industries investigated, wages increased, during the war, from y 2c to 8c a day in 22 industries. In 53 industries wages decreased from 5c to 18c a day. Among the latter are included the iron workers in the Osaka government ammunition factories, the moulders, machinists and the employees of the government tobacco monopoly. Among the 25 representative industries, the ship-builder is most highly paid. He receives a remuneration of from 15 to 96c a day. The lowest average wage in these 25 trades is 17c, the highest 61c per day. Prices of necessities are higher by 50 per cent, than before the war. As a result there have been numerous strikes, in spite of government oppression. Many were won, but more frequently they were put down relentlessly by police force. Although the Japanese worker is a highly capable mechanic, has advanced rapidly in the sphere of technique, and is able to execute highly complicated work on modern machines, he is politically and economically utterly powerless to resist the oppressive bureaucratic ruling class. The frequent strikes and labor uprisings are desperate revolts of illtreated workers against their oppressors, against unbearable conditions of labor and economic pressure under a steadily rising cost of the necessities of life.

For a number of reasons the Japanese workers cannot, at the present time, assume governmental power by mass revolt or collective organization. The Japanese government rests its power upon a powerful army of well organized bureaucratic followers, its officials numbering over 200,000 men. There are, in the very nature of things, staunch upholders of the bureaucracy, well organized for the work of exploiting the great masses. This almighty bureaucracy of Japan dominates and monopolizes the army and navy. In its capacity as the greatest buyer and contractor of every conceivable kind of merchandise, from shoes to superdreadnaughts, it controls the most powerful capitalist interests. The latter submit to the dictates of this bureaucracy willingly, because it lies in their interest to do so. Riding upon the growing capitalist forces, our bureaucratic government has, in recent years, become bolder and more determined in its attitude, and quite outspoken in matters of foreign policy. It is determined to advance its long cherished ideals of imperialism in the Far East. The past has taught Japanese imperialists the profits to be gained from territorial conquest, that extended influence and power will mean an increased officialdom, an expanding army and navy, creating a widening sphere of influence and activity for the governmental powers.

While the vast army of bureaucratic government supporters profits by every expansion of Japanese capitalist influence, the Japanese working class has done its burdens, the load of armament and national expenditures. The growing influence of the Japanese ruling class in the world means for them ever greater oppression, ever growing burdens.

About five years ago the government increased the salaries of all civil officials and military officers by 25 per cent, and a new increase is again being contemplated. Last year the pensions paid out to the members of this class amounted to an aggregate sum of $17,930,000. This equals the annual wages of 156,588 workers at 30c a day, a daily wage that considerably exceeds the wage of the average Japanese laborer. Under the present pension system the retired officer of the lowest rank and the police receive a pension amounting to one-half his salary for life, after 15 years of service. This class constitutes the heaviest burden upon the shoulders of the people. It sacrifices every interest and resource of the nation to its own self-aggrandizement, and under its rule capitalism flourishes; the two advance, hand in hand, in their work of exploitation.

I have shown how our government helps the capitalist class of Japan in the financial and economic fields. But in social and other ways, too, the burdens of the country are shifted upon the heads of the workers. In theory every able-bodied young man at 20 is conscripted into the army. But in actual fact the youths of the rich are permitted to escape from this universal duty. Government officials, students in the secondary schools, and young men whose financial status permits them to go abroad are exempted.

Still, the great powers that lie in the hands of the ruling class in Japan would finally arouse the resentment of the laboring masses were it not that the latter have been driven into submission by an incredible surplus of labor power in every field of industry, except in the cotton-spinning industry, where cruelty and overwork rapidly thin out the ranks of the working girls. Japanese workers are not permitted to emigrate to foreign countries, not only to America, with which the Gentlemen’s Agreement exists, but to other countries as well. There is, to be sure, a brutal immigration company which supplies contract labor to Brazil. Furthermore, the Japanese laborer is free to go to Manchuria or China. But here even our poorly paid Japanese workers cannot compete with the cheap labor of the natives. Even the Manchurian Railroad and the rich collieries there prefer Chinese workingmen. Under such conditions the Japanese worker is absolutely powerless at home, under the increasing exploitation of both imperialistic and capitalistic interests.

Japanese imperialist and capitalist classes will emerge from the war vastly strengthened. For the first time in its history Japanese exports have exceeded its imports. Up to 1914 Japan was a borrowing nation, a debtor to Europe. The war has changed this situation. To-day Japan is financing some of the Allies, notably China, Russia, and even England. In July, 1916, the national wealth of Japan was $135,560,000. But in July of the present year the figures show $449,000,000, and its wealth is increasing from week to week. This means that capitalism in Japan will have a free hand to develop her industries and her commerce, will mean greater opportunities of exploiting its surplus labor supply. Imperialism, with the support of a strong bureaucracy, will have greater and more intensive powers of oppression, powers hitherto restrained by the necessity of heavily taxing the population to cover the financial straits of a nation drained by large debts and heavy subsidies. To-day money is plentiful, and the army will grow In leaps and bounds. This situation brings Japan face to face with a dangerous future. She will be misdirected and misguided by a war-crazed imperialistic class, by thirsty capitalists and newly created millionaires. Already we see in the utterances of the present Premier, Count Terauchi, whose land-cry policy has evolved out of the Imperial Household itself, a sign of the era that is to come. An imperialistic autocracy, directed by the Mikado, but in reality under the leadership of Prince Yamagata, the very head of the Japanese bureaucracy, will drive the nation onward, utterly irresponsible to the best interests of its people.

It is the irony of fate that Japan’s imperialism should join in the battle-cry—to crush Prussian militarism, to make the world safe for democracy—while its own system of militarism is crushing the Formosans, the Coreans, and even the Manchurians, as well as the Japanese workers themselves. As an internationalist, I oppose, therefore, the present imperialistic policy of Japan, that tramples down the rights and liberties of socialists and workers, and willfully permits the capitalist class to exploit working girls and children heartlessly and cruelly. I want to see the autocratic imperialism destroyed, once and for all time, in Japan, as in Germany, for the liberation of the unhappy toiling millions.

I know that the armed peace that is to come over the Pacific will not bring a real, a democratic and a lasting peace to the workers of America and Japan. On the contrary, it will become the greatest menace and danger to both countries, and to the world.

Militarism built upon the backs of an unorganized working class, with the full support of an ever-growing capitalism, will know neither constraint nor consideration. It can and it will sacrifice everything to satisfy its greedy thirst.

The only true solution of this menace and the avoidance of a possible conflict of the two Monroe Doctrines—that of the Americans and that of the Asiatics on the Pacific—must be sought in the potential power and influence of the working classes of the countries concerned. As I have shown, the Japanese workers are not organized, and consequently are powerless. We must look to and rely on others. But the American workers are organized, are powerful and influential. The future peace of the Pacific largely rests upon them. And we must work to that end!

The Class Struggle is considered among the first pro-Bolshevik journals in the United States and began in the aftermath of Russia’s February Revolution. A bi-monthly published between May 1917 and November 1919 in New York City by the Socialist Publication Society, its original editors were Ludwig Lore, Louis B. Boudin, and Louis C. Fraina. The Class Struggle became the primary English-language paper of the Socialist Party’s left wing and emerging Communist movement. Its last issue was published by the Communist Labor Party of America.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/class-struggle/v1n3sep-oct1917.pdf#page=39