The full Debs–love and rage, Millenarianism and Marxism, pathos and passion–in this wonderful essay on the many things he learned through his prison experiences. Written shortly after his release from federal prison at the end of 1921, it is here presented as an appendix to Debs’ only full length book, and his last work. Both a personal memoir from his times served and an analysis of the carceral system from Debs, disfranchised felon and prison abolitionist.

‘Studies Behind Prison Walls’ (1922) by Eugene V. Debs from Walls and Bars. Published by the Socialist Party, Chicago. 1927.

The prison has a place peculiarly and entirely its own among the institutions of human society. It is there that the human being is detached from his former associations and isolated under rigorous discipline to expiate his alleged offence against society. It is the one place to which men go only under compulsion and in humiliation and shame.

When I was a boy the very word penitentiary had a shocking effect upon my sensibilities, and of course I did not dream that I would ever serve a sentence as a convicted felon within its walls. I had never seen a penitentiary, but I had seen the filthy county jail in the town in which I lived, and through its barred windows I saw the imprisoned victims and heard their foul and damning imprecations.

This gave me some idea of what the penitentiary must be like and I wondered even then if it were not possible to deal with our erring fellow men in a more humane way than by committing them into foul dungeons and treating them as if they were beasts instead of human beings.

Later in life when I had become active in the labor movement and had a part in the strikes and other disturbances of organized workers, in the course of which the leaders were not infrequently arrested and sent to jail, I came to realize that the prison could be used for purposes other than confining the criminal; used as a club to intimidate working men and women after their leaders had already been incarcerated; used as a silencer upon any expression of opinion that might not happen to be in accord with the administrative power.

So, I understood from the beginning that all men who were sent to jails and penitentiaries were not criminals; indeed, I have often had cause to think that the time may come in the life of any man when he would consider it necessary to go to prison if he would be true to the integrity of his own soul, and loyal to his inherent, God-given sovereignty as a human being. Such thoughts would come to me after my many visits to jails and penitentiaries to call upon friends and associates in the labor struggle incarcerated there.

It was in the railroad strike of 1877 that I had my first experience in seeing my associates in the railroad union sent to jail, and I began to realize that if I continued my activity I might some day go there myself. Less than twenty years later I had my first interior view of the jail as an inmate, and this experience awakened in me a keen interest in the prison and its victims. The penal question has been to me an absorbing study ever since.

The notorious old Cook County jail in Chicago, for years the choicest picking for grafting politicians, reeking with vermin and infested with sewer rats, comes vividly to memory as these lines are written. It was there that I was initiated into the moralities and mysteries of prison life. I saw at a glance what that filthy pen meant to the unfortunate creatures confined there, and at once my sympathy was quickened, and I felt myself drawn to them by a fellow feeling which grew stronger with the passing years.

Soon afterward I was sentenced to the McHenry County jail in Woodstock, Illinois, to serve a term of six months upon the charge of contempt of court for the violation of an injunction issued by the federal court during the great Pullman strike in 1894. I had pleaded in vain for a jury trial.

Fortunately for me and my convicted associates of the American Railway Union, the filthy Cook County jail was over populated at the time we were sentenced, in consequence of which we were transferred to the county jail in Woodstock. The farmers in that vicinity did not relish the idea of my being “boarded” among them even as an inmate of their jail. They had been reading the daily newspapers and had concluded that I was too dangerous a criminal to be permitted to enter the county, and it was reported that they would gather in numbers at the station on my arrival and attempt to lynch me, or at least prevent me from disembarking. When we arrived at Woodstock a number of them were at the station, but they had evidently been advised against carrying out their enthusiastic program for they made no hostile demonstration.

The jail at Woodstock was a small affair and clean for a county lock-up. I soon had a satisfactory understanding with the sheriff, a veteran of the civil war, and got along without the least trouble. During the latter period of my term I conducted an evening school for the benefit of the prisoners, and on my leaving they presented me with a set of resolutions expressive of their gratitude which is still a cherished testimonial in my possession.

Some years later when I was touring the country as a presidential candidate I made a special visit to Woodstock and received a great ovation from the visiting farmers and the townspeople, among whom was the sheriff who had been my jailer and had become my friend. On another occasion I was invited there to address a meeting at the City Hall, the daughter of the sheriff, head of the Relief Corps of the G.A.R., having charge of the arrangements.

Almost twenty-five years passed before I had my next prison experience. The world war was in progress and the excitement was intense. I had my own views in regard to the war, and I knew in advance that an expression of what was in my heart would invite a prison sentence under the Espionage Law. I took my stand in accordance with the dictates of my conscience, and was prepared to accept the consequences without complaint. The choice was deliberately made, and there has never since been a moment of regret. It was not because I yearned for imprisonment that I took the position that human beings had a higher call and a nobler purpose in life than slaughtering each other and hating those they could not kill, but simply because I could take no other, although realizing fully that the choice led through prison gates.

A sentence of ten years followed my trial at Cleveland in which I permitted no witnesses to testify in my behalf and no defense to be made. When the government’s attorneys were satisfied that they had concluded their case against me, I addressed the jury, not as a matter of defense of the speech that had resulted in my arrest, trial and conviction, but in an attempt to amplify and supplement it so that there could be no possible mistake as to my beliefs and opinions with respect to the subject in controversy. It was an unusual and surprising proceeding in a courtroom. I was entirely prepared to receive the sentence of ten years pronounced by the judge. I had stood upon my constitutional right of free speech, and in this attitude I had the sanction and support of tens of thousands of people who had no sympathy with my political views.

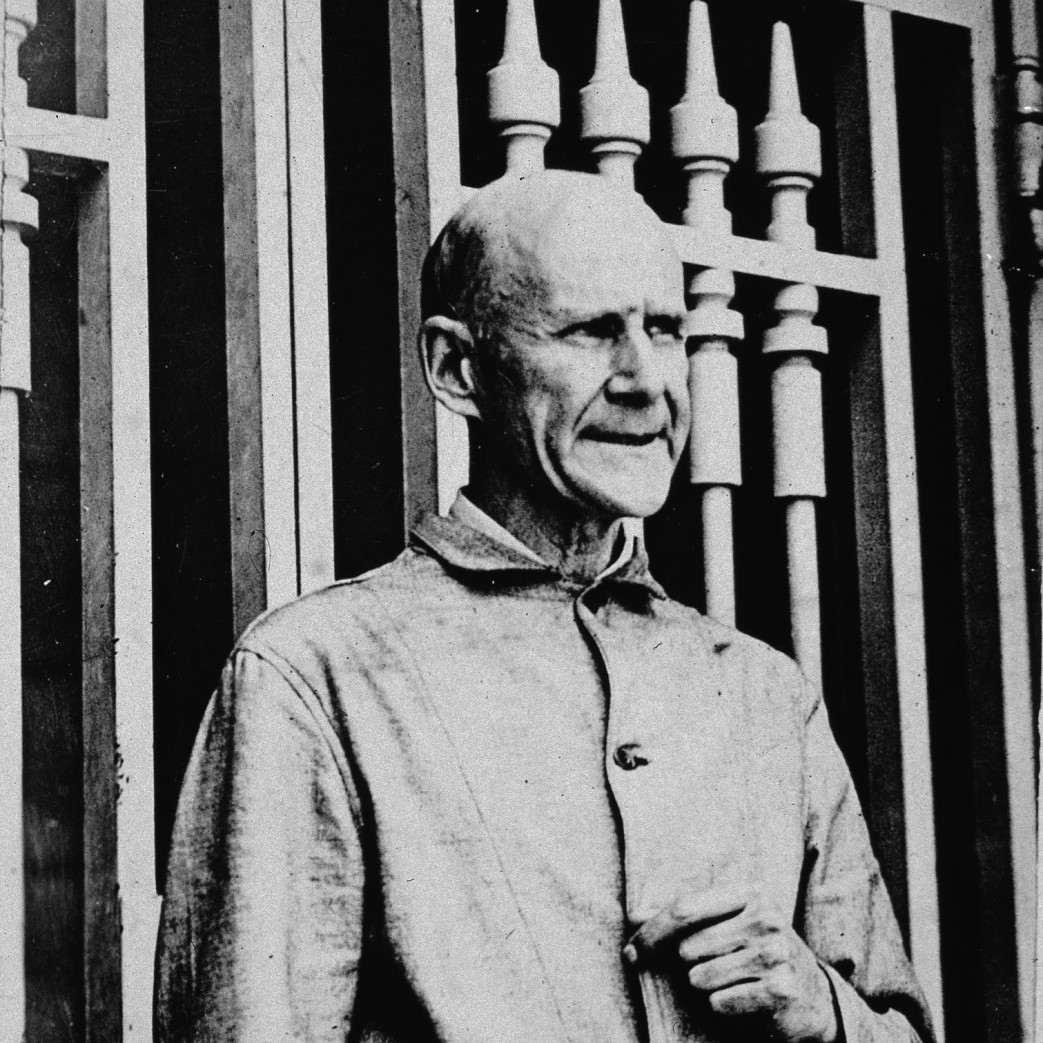

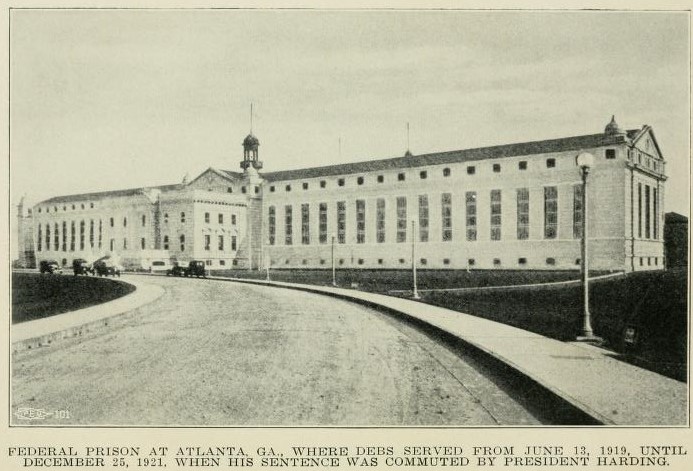

On the evening of April 13, 1919, I was delivered by United States Marshal Lap and his deputies of Cleveland to Warden Joseph Z. Terrell, of the West Virginia State Penitentiary at Moundsville to enter upon my sentence. I was permitted to serve but two months at Moundsville when the order came from Washington for my transfer to Atlanta Federal Prison. My brief sojourn at Moundsville was entirely satisfactory as a prison experience, for after my arrival there I was introduced to the various officials and came into intimate and pleasant contact with all the prisoners.

These experiences were preliminary to my adventure at the United States Penitentiary in Atlanta, where I was taken on June 14, 1919, and served as an inmate until Christmas Day, 1921.

With this introductory sketch I shall now enter upon the story of my actual prison life and my study of the prison as an institution, the inmates confined there, the rules and conditions under which they serve their terms, and the effect of their prison experience upon their subsequent lives.

Personally, I feel amply rewarded for the opportunity that was given me to see and know the prison as it is, for while I was a prisoner at Atlanta I learned more of a vital nature to me than could have been taught me in any similar period in the classroom of any university.

A prison is a wonderful place in the opportunity afforded not only to study human nature in the abstract, to examine the causes and currents of motives and impulses, but also to see yourself reflected in the caricatures of your fellow men. It is also the one place, above all others, where one comprehends the measureless extent of man’s inhumanity to man.

I hate, I abominate the prison as it exists today as the most loathsome and debasing of human institutions.

Most prisons are physically as well as morally unclean. All of them are governed by rules and maintained under conditions which fit them as breeding places for the iniquities which they are supposed to abate and stamp out.

When I entered the Atlanta Prison it was on a common footing with all the rest of the prisoners. I expected no favors and would accept no privileges that were denied to others. From the moment I entered there I felt that I was among friends, for the prisoners accorded me an enthusiastic welcome which I knew was genuine on their part. I at once made up my mind that it would be my constant endeavor to serve these fellow prisoners of mine in every way that I could and at every opportunity that presented itself. I was not there long before I realized that my attitude toward the convicts was understood by them and reciprocated in ways that shall always remain in my memory in tender testimony of the human fellowship that can blossom even in a prison if nourished by kindness of heart.

When I was put into a second-hand prison suit of blue denim I felt myself one with every prisoner in Atlanta. During the first two months I was placed in a cell which was already inhabited by five other convicts, and these inmates did everything that human beings could possibly do to make me comfortable and my stay a pleasant one. They were constantly seeking ways and means to share with me whatever they had, and from these simple souls I learned something about unselfishness, and thoughtfulness, and respect for another’s feelings— qualities that are not too common in the outer world where men are more or less free to practice them without being watched by brutal guards with clubs in their hands eager to proclaim their authority with the might of the bludgeon.

We sat side by side and ate the same wretched food together, and after our evening meal in the general mess we spent fourteen consecutive hours together locked in a steel cage. I found my cellmates to be just as humane as any men I had ever met in the outer world.

I have heard people refer to the “convict countenance”. I never saw one. The rarest of human beings, the most cultured and refined amongst us might in time become brutal by the blighting and brutalizing influence of the prison if they should permit themselves to yield their spirit to the degrading and debasing atmosphere that permeates every penitentiary in the land.

By far the most of my fellow prisoners were poor and uneducated men who never had a decent chance in life to cultivate the higher arts of humanity, but never in all the time I spent among those more than 2,000 convicts did one of them give me an unkind word.

There is infinite power in human kindness. Every one of those convicts without a single exception responded in kindness to the touch of kindness. I made it my especial duty to seek out those who were regarded as the worst specimens, but I never found one who failed to treat me as decently as I treated him. My code of conduct toward my fellow prisoners had the same efficacy in prison that it had elsewhere. In dealing with human beings I know no race, no color and no creed. At the roots I think we are all alike, governed by similar impulses that have more or less the same results, depending upon the circumstances in which we find ourselves placed, and considering the conditions that attend us. I judge not and I try to treat others as I would be treated by them.

But in prison the human element is sadly discounted and men are made by cruel and senseless rules to fit into the criminal conceptions of them which prevail under the prison regime.

The prison, above all others, should be the most human of institutions. A great majority of the inmates are there because of their poverty and the direct or indirect results of poverty. Their misfortune in life is penalized and they are branded as convicts for the rest of their lives.

If an intelligent study could be made of each individual case in a federal or state prison and the result truthfully placed before the people the nation would be horrified at the cruel injustice which would be revealed. Most of the victims of prison injustice are without friends of influence to intercede in their behalf, and society in the aggregate has no concern in them whatsoever.

The average prison is in the control of politicians who know little and care less about what takes place behind the walls. Prison officials are placed in responsible positions to reward them for their political services and not with reference to either their character or qualifications for the office.

The warden and deputy warden of a prison should have exceptional qualities to fit them for the discharge of their important duties, and they should be among the most humane of men.

One of the first things I discovered in Atlanta prison was the wretched food provided for the prisoners and the disgusting manner in which it was cooked and served. The menu was confined to a few poor articles which palled upon the appetite and was the source of universal daily complaint and dissatisfaction.

Soon after I entered prison the question occurred to me: why are men who work here not paid for their labor? They are here under punishment for having stolen perhaps a few dollars and promptly upon their incarceration the government or the state proceeds to rob them of their daily earnings, compelling them to work day after day without a cent of compensation. The service which the state exacts from a convict should be paid for at the prevailing rate of wages to be placed to his credit on the books, or shared with his family, so that on leaving the prison he would not have to face a hostile world in a shoddy suit of clothes and $5.00 in his pocket as his sole capital with which to start life anew.

The clubs and guns in the hands of guards present a picture well calculated to reveal the true character of the prison as a humanizing and redeeming institution.

As a matter of fact, the prison is simply a reflex of the sins which society commits against itself. The most thorough study of prison inmates that I was able to make in the course of my intimate daily and nightly contact with thousands of them convinced me beyond all question that they are in all essential respects the same as the average run of people in the outer world. I was unable to discover the criminal type or the criminal element of which I had heard and read so much before I had the opportunity to make my own investigation. That there are moral and mental defectives in prison is of course admitted, but the number is not greater, nor are the cases more pronounced, than may be found outside of prison walls.

However, in dealing with these imprisoned and helpless beings in the prevailing prison spirit and under the omnipresent iron clad regulations, they must necessarily be regarded as a dangerous and vicious aggregation in order to justify the brutal and corrupt system which, under the pretense of reformation, preys upon their misfortune. There are many flagrant abuses and evils in the present prison regime and these have their source and incentive primarily in being in the control of politicians who wax fat out of the misery of convicts by delivering them, in many states, to heartless contractors who in turn sweat and rob them, not only of their labor but of their health and very lives. The prison labor contractor is the most merciless of slavedrivers.

I have seen enough of this shocking cruelty to forever damn the institution in which such an outrage upon unfortunates is practiced. In the matter of convict labor the state virtually sells its outcast citizens into abject slavery so that thieving contractors, the pals of politicians who control the prison, may fatten upon the proceeds of their crimes against so-called criminals.

Are the vultures who thus prey upon the helpless, robed as they are in the soft raiment of respectability, not actually lower morally than the victims of their inhumanity and piracy? And if men should be sent to prison for robbery, are not these official mercenaries the very creatures who, instead of controlling the prison, should themselves be under its own brutal regulations?

That the vicious and corrupting abuses herein set forth were recognized years ago by men who honestly attempted to correct them is clearly stated in a report to the New York State Legislature issued more than half a century ago by Professor E.C. Wines and Professor Theodore W. Dwight, then Commissioners of the Prison Association of New York, from which I quote as follows:

“Upon the whole it is our settled conviction that the contract system of convict labor, added to the system of political appointments, which necessarily involves a low grade of official qualification and constant changes in the prison staff, renders nugatory, to a great extent, the whole theory of our penitentiary system. Inspection may correct isolated abuses; philanthropy may relieve isolated cases of distress; and religion may effect isolated moral cures; but genuine, radical, comprehensive, systematic improvement is impossible.” (Italics are mine).

As long as the prison is in control of politicians and under the supervision of their creatures, its callous indifference to the inmates, its internal vices and abuses, and its external reaction in furnishing society with a steady stream of criminals trained in its own institution will continue, and isolated instances of superficial improvement will not materially reduce the evil and corrupting power.

I am not at all inclined to exploit my personal prison experience and should prefer to omit that element entirely, were it not necessary to the purpose of this article to include some reference to it. It is to be doubted if there was ever before in prison history a case parallel to my own in point of experience and results issuing therefrom.

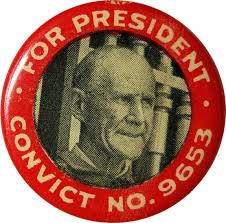

I had been four times the candidate for President of the United States of the party representing the class toiling in penury and suffering from whose ranks are recruited, under the lash of poverty and misery, with but few exceptions, the victims of penal misrule. Since my early boyhood, and practically through my entire life, I had been in intimate association with working people and those who are generally regarded as the “lower class.” My understanding of their conditions, my perception of the basic social causes that had preceded their predicament, and my sympathy with them even in their transgressions, which is usually the result of their wretched lot, had preceded my entrance through the prison gates.

The entire prison seemed to join in the sympathetic reception accorded me. The question was frequently asked, sometimes sneeringly by the guards, and sometimes in a spirit of wonder and admiration, by what magic I held the interest of my fellow prisoners and won their affection and devotion. The answer is a quite simple one. I recognized in each of them my brother and treated him accordingly. I did not moralize or patronize my fellow convicts in the least. Men who are caged and watched, spied upon and hunted like animals develop certain latent instincts that become amazingly keen and discerning. Among these is the instinct to divine what is in the heart of those who approach them. They have been robbed of their respectability and forever denied the chance to regain it, and, sensitive as they surely are to this circumstance, they are not apt to be impressed by those who pose before them as their moral superiors.

They recognize no redeeming influence in moralizing rebuke. They resent being patronized, even the most ignorant of them, unless in the prison atmosphere they have degenerated into stool pigeons. No one who condescends to serve these prisoners can win their graces or exercise any salutary influence upon them. They hunger for sympathy, but it must be genuine, human, warm from the heart.

The late Father Michael J. Byrne, of the federal prison at Atlanta, was in all respects the finest prison chaplain I have ever known. I had no church affiliation, and for reasons of my own I rarely attended devotional exercises at the chapel, but I loved Father Byrne and we would talk together many hours in my little room in the prison hospital.

Devotional offerings in the name of the merciful Jesus, who loved the poor and freely forgave their sins, on an altar presided over by grim visaged guards with clubs in their clutches ready to fell the worshippers was not compatible with my sense of religious worship. Before I entered Atlanta prison attendance at chapel was compulsory. Almost from the start I declined to go myself, partly because of the hideous mockery which the scene and setting made of sincere worship, and I think that as a result of my resolute protest the rule was modified and attendance became voluntary, but the guards with clubs in their fists remained.

Father Byrne ministered in the spirit of loving service to all alike, no matter how low some might seem in the eyes of others, and that is why he and I instantly became friends and co-operated with each other to the full extent that my restrictions as a convict would allow. It may seem strange, but it is nevertheless true, that not only do the prison rules not countenance inmates being kind and helpful to each other, but on the contrary, they forbid their being so, and encourage their spying upon, betraying and hating one another so that all may the more readily be kept in subjection.

In the prison hospital an inmate may be dying, but the rules forbid him being visited by his fellow prisoners; each convict must keep to himself no matter how great may be his desire to clasp the hand of a fellow prisoner whose affection he may have won in the course of their suffering and struggling together against the cruel and senseless regulations. This is one of the prison rules that I confess violating with impunity. I should have preferred going to the dungeon, known in prison parlance as “the hole,” on bread and water, rather than to have obeyed that rule. As a matter of fact, nearly every prison rule is violated by every convict who stays any length of time in prison. If he would remain a human being he must of necessity break the rules in order to live. Men cannot, and will not, be unsocialized even in a prison whose rules attempt to wreck and ruin human character and personality in the quickest possible time by the harshest possible methods. But the group psychology prevails, and the rules go by the board, though often at the expense of great suffering on the part of those who transgress them. Almost every prisoner who came to the hospital expressed an immediate desire to have me come and see him. Invariably I did so as soon as possible. I was able in many ways by voluntary ministration to ease their suffering and brighten their wretched days. Father Byrne observed a remarkable change in the moral atmosphere of the hospital after I entered there. Men no longer used foul language or told smutty stories. The relation between the guards and inmates had completely changed. It was as if the hospital building was now occupied by a harmonious human family instead of a lot of sullen and incorrigible convicts.

Both the warden and his deputy commented on the change which none appreciated more than Father Byrne.

A visiting reporter once asked Father Byrne how it was that I held such moral power over the prisoners. His answer was: “He just loves them; he talks to them and then they’re different. There is something about him that wins and changes them.” There is nothing mysterious or occult about the “something” to which Father Byrne referred. It was merely an active manifestation of human kindness which all of us possess, but which we are prone to smother beneath a crust of indifference to the suffering of our fellow men.

The day before the death of this noble-spirited chaplain he sent me a beautiful and touching telegram congratulating me upon my release from prison. The message read: “Heartiest congratulations and well wishes from your best friend. God bless you. Michael J. Byrne, Catholic Chaplain, U.S. Penitentiary.” Father Byrne is at rest. His memory will be cherished by the thousands of convicts to whom he gave himself as freely and ministered as lovingly as the Nazarene Himself might have done in his place.

Love and service constitute the magical touchstone; they are, when fully developed and truly expressed, one and inseparable, and more imperatively needed in prison than in any other place on earth.

There is where Jesus Christ would be His perfect self in tender and sympathetic ministration, and He would require neither guns nor clubs to protect His person from insult or assault.

It is when men are most prosperous in their individual pursuits that they are more apt to be thoughtless and indifferent to the fate of others, but when they are plunged into a common abyss of misery and suffering they are likely to become sympathetic and responsive to the touch of kindness, and there is more redemptive influence in a word of love and sympathy than in all the harsh rules ever devised and all the brutal clubs ever wielded to enforce them.

There was never a moment of mine in Atlanta prison that was not mortgaged in advance. Many of the prisoners could neither read nor write, and they would come to me to have me read and answer their letters, or to fill out their blanks for pardon, parole or commutation, although much of this had to be done by stealth as it was in violation of the rules, and was several times arbitrarily forbidden by the guards, especially when prisoners were caught leaving my room. I heard their sad stories, listened in sympathy to their tragic appeals, placed my hand on their shoulders and counselled them as an elder brother, and while I was able to do but a mere trifle of what my heart would have done for them, I sensed the appreciation and gratitude that embraced the entire body of prisoners of all colors, creeds and conditions.

The scene that occurred upon my release when these 2,300 prison victims clothed as convicts, yet with human hearts throbbing beneath their tatters, spontaneously burst their bonds, as it were, rushed to the fore of the prison on all three of its floors and crowded all the barred window spaces with their eager faces, cheering while the tears trickled down their cheeks — this scene can never be described in words, nor can it ever be forgotten by those who witnessed that extraordinary and unparalleled demonstration.

In that brief moment prison rules were stripped of their restraining power, and men though in prison fetters gave lusty expression to their beautiful human impulses. It was the most deeply touching and impressive moment and the most profoundly dramatic incident of my life. Men and women on the prison reservation, including the officials who bore witness to that unusual scene, stood mute in their bewilderment. Never before had such a thing occurred, and never in the wildest stretch would it have been deemed possible.

There was a reason for this unheard of demonstration, and it was not all of a personal nature. I arrogate to myself no importance whatever on account of having won the friendship of these convicts. They did vastly more for me than I was able to do for them, and the only point I make in this connection is that if the prison were conducted in the spirit and with the understanding that we convicts had for each other the whole penal system would at once be revolutionized; instead of being a bastile for debasing and destroying the unfortunate it would become in the true sense a boon to society as a reclamatory and redemptive institution.

The prison as a prison in the common acceptance of that term will always be a tragic failure. It is not only anti-social, but anti-human, and at best is bad enough to reflect the ignorance, stupidity and inhumanity of the society it serves. But this is not to say that improvement of the prison while it lasts should be discouraged. On the contrary, until the time comes when social offenders are placed under scientific treatment instead of being punished as criminals, every effort should be put forth to improve the moral and physical condition of our county jails, our state prisons and our federal penitentiaries.

For myself, I heartily commend all that is being done to arouse the people to a consciousness of the festering evils which now thrive in these places. There needs to be created a public sentiment that realizes that for its own self -protection the community must clean up the prison as far as that may be possible and make it a place where criminal tendencies may be checked and overcome instead of being encouraged and confirmed as they now are to the ruin of their immediate victims, and their increasing detriment to society.

Space will not permit more than a brief summary of the fundamental changes required to humanize the prison.

First of all, it should be taken out of the hands of politicians and placed under the supervision and direction of a board of the humanest of men with vision and understanding. This board should have absolute control, including the power of pardon, parole and commutation. Such a board as this would at all times be in immediate touch with the prisoners and have intimate knowledge of prison conditions and possibilities for improvement.

The contract system, wherever it prevails, is an unmitigated curse and should be summarily abolished.

Prison inmates should be paid for their labor at the prevailing rate of wages which should be placed to their credit in the books of the institution or shared with their families so that when the convict is released he will not have to return to a sundered home and face a hostile world.

Not a gun nor a club should be in evidence inside the walls.

The prisoners themselves, at least 75 per cent of whom are dependable, as every honest warden will admit, should be organized upon the basis of self-government and have charge of the prison, select their own subordinate officers, their own guards, their shop and other foremen; establish their own rules and regulate their own conduct under the supervision of the prison board.

Under such an organization the morale of the prison would at once improve, the spirit of the prison would be humanized, there would be better discipline, more incentive to work, and better results in every way, and all at a greatly reduced expense to the community.

There will be men to challenge these proposals as visionary, if not vicious, but I would prefer nothing more than the opportunity to vindicate my faith in human nature by being permitted, without any pecuniary compensation, to make such a demonstration.

Walls and Bars by Eugene Victor Debs. Published by the Socialist Party, Chicago. 1927.

Contents: Foreword, Acknowledgements, Introduction by Debs (July 1, 1926), The Relation of Society to the Convict, The Prison as an Incubator of Crime, I Become U.S. Convict, No. 9653, Sharing the Lot of Les Miserables, Transferred From My Cell to the Hospital, Visitors and Visiting, The 1920 Campaign for President, A Christmas Eve Reception, Leaving the Prison, General Prison Conditions, Poverty Populates the Prison, Creating the Criminal, How I Would Manage the Prison, Capitalism and Crime, Poverty and the Prison, Socialism and the Prison, Prison Labor Its Effects on Industry and Trade, Studies Behind Prison Walls, Wasting Life. 248 pages.

PDF of book: https://archive.org/download/wallsbars00debs/wallsbars00debs.pdf