A review of four Spanish Civil War-themed etchings, included, by Luis Quintanilla from 1938. Quintanilla was an artist revolutionary imprisoned in the aftermath of 1934’s revolution in Spain and active during the war in Madrid. He moved to New York shortly after this article as Franco’s armies advanced.

‘Luis Quintanilla: Four New Drawings’ by Elliot Paul from New Masses. Vol. 28 No. 12. September 13, 1938.

NOWHERE in the world is the relationship between the artists and intellectuals and the workers more cordial and intimate than in Spain. And of all the artists there Luis Quintanilla is perhaps the best known to the farmers, artisans, and soldiers who are fighting for their country’s independence.

For two or three years before Alfonso’s corrupt monarchy collapsed, Quintanilla’s studio was an arsenal and he worked there with the shadow of arrest and of death behind him as he faced his easel. On that day in April when the monarchy fell, three men were standing in a doorway near the royal palace and all were agreed that the crowd gathered there should be reassured in some way, since armed Guardias who had mowed the people down on other occasions were patrolling the courtyard. The three men were Negrín, now Premier of Spain, Barral, a sculptor who was killed defending Madrid, and Quintanilla. The latter, being the most agile, climbed the front of the palace and placed a Republican flag there while Alfonso was still cringing inside. Then he told the commander of the Guardias to take his men away and keep them out of sight. The officer obeyed.

After the first revolution, the traitorous agents of capitalism tried to nullify its effects; the well-intentioned revolutionists rose against them, and Quintanilla, with nearly all the prominent Spaniards who can hold up their heads without shame today, went to prison. There he worked, and drew a terrific indictment against his country’s enemies while his fate was being decided by judges who wanted to have him killed but didn’t dare.

When a graver moment came and the Spanish people were obliged to improvise a defense against fascist aggression, a willing crowd of workers and students followed Quintanilla without question and took the Montana barracks away from an armed and trained force.

It is not incompatible for a modern man to be a patriot, a soldier, and a revolutionist and also to be an artist. In the case of Quintanilla, it is necessary for him to be all that he is. He is filled with energy and determination, he is sensitive to an almost painful degree, he does not let the enormity of, his own or his country’s sorrows overwhelm him. As long as he lives he will protest, he will hold up to scorn the traitors and the bootlickers, he will fix with terrible images the memory of democracy’s agony.

The first drawing is entitled Franco’s Dream. And in order properly to understand the Spanish tragedy it must be known that Franco, the self-styled savior of Spain, has not the forceful dog-face and he-man style of Mussolini nor the comedy mustache and the weeping countenance of Hitler. I may as well come out with it. Franco is a cute and plump little fairy. Consequently, his dreams, as portrayed by Quintanilla, are devoid of women. Behind him, guarding his slumber, stand his mercenary Moors whom he sends to the front to be killed when he owes them too much money. In the distance are ruins of men and of buildings. Lolling ecstatically in the left foreground is a fat bourgeois and a squatting figure symbolic of superstition and ignorance. The faint stench of the Middle Ages hangs over the spectacle.

I have no hesitation in saying that a careful study of this drawing will throw more light on the Spanish situation than reams of newsprint.

The second drawing is in no way symbolic. It shows an old man and an old woman murdered in their beds by the Moors who have been brought into Spain to aid Franco’s program of civilization. What impresses one is the uselessness of the murder. One does not feel sorry for the old couple. One does not hate the Moors. It is the contempt for Franco, his masters, and his colleagues, that rises to the surface.

Ah, no, it is not by killing the old and defenseless that power is gained and held.

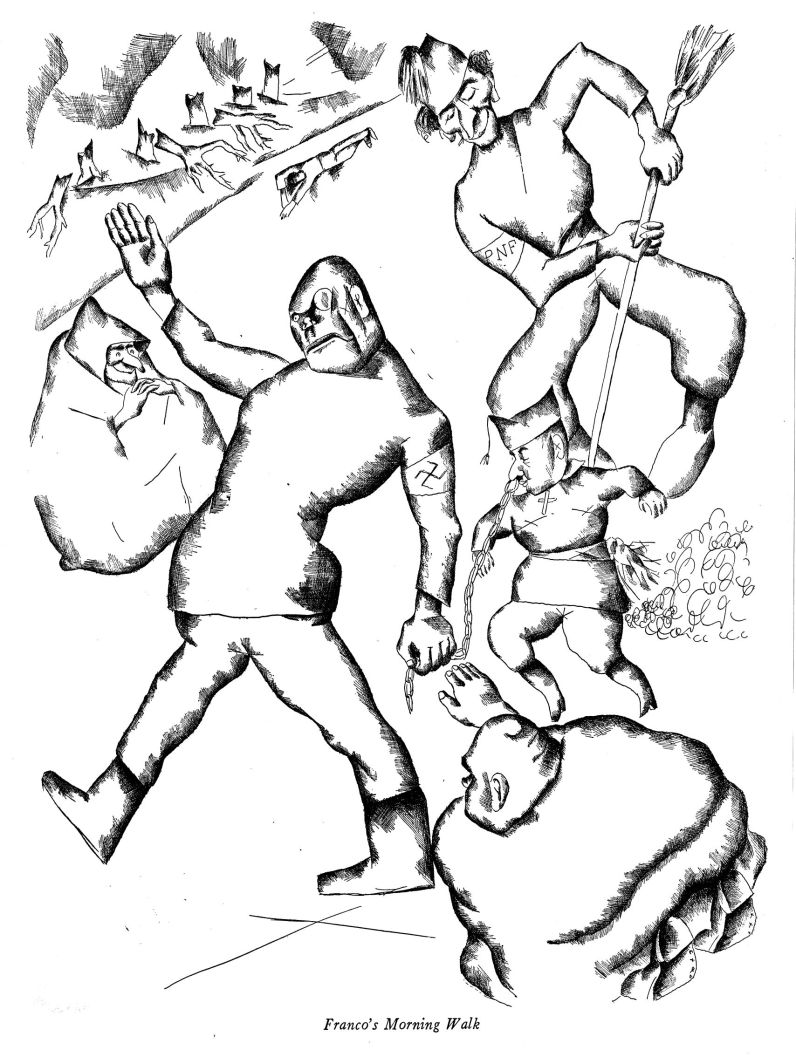

The third drawing depicts Franco, the great patriot and führer, taking his morning walk, led by a chain and nose-ring by one of Hitler’s prize Nordics, propelled from behind by a broom in the hands of one of Mussolini’s jolly Aryans. Broken trees and a corpse are in the background, and in the middle distance the familiar figure of ignorance and superstition. Hypocrisy kneels and gives the fascist salute as the self-appointed dictator passes by. Keen observers will notice a spider web.

The last drawing in the series is a self-portrait. Quintanilla sticks to his work, departing dreams of old Madrid dissolving and the sickening parade of tricksters and invaders reduced to pigmy size beneath him.

I think the streets and squares of Madrid will ring again, some time, to Quintanilla’s laughter. I think he will receive his friends there with his old time grace and gusto. The flag he placed on the palace still waves there. One must not forget that. The honest men of his country whose work and spirit he has admired and to whom he has dedicated unreservedly his talents are still in the fight. Give them ammunition, give them half a chance and they will place democracy high and safely on the Spanish plains and its fragrance will enhance the beauty of Mediterranean ports. If any of the Basques are left, that region will flourish again. And the bravery of the Asturians will be carried on by the survivors.

The only possible ending of any article, however brief or long, about Spain is a renewal of the plea to Americans to be fair and decent, also wise and prudent, and give the loyal Spaniards the means of defense.

The New Masses was the continuation of Workers Monthly which began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Communist Party publication, but drawing in a wide range of contributors and sympathizers. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and The New Masses began. A major left cultural magazine of the late 1920s to early 1940s, the early editors of The New Masses included Hugo Gellert, John F. Sloan, Max Eastman, Mike Gold, and Joseph Freeman. Writers included William Carlos Williams, Theodore Dreiser, John Dos Passos, Upton Sinclair, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, Dorothy Parker, Dorothy Day, John Breecher, Langston Hughes, Eugene O’Neill, Rex Stout and Ernest Hemingway, Artists included Hugo Gellert, Stuart Davis, Boardman Robinson, Wanda Gag, William Gropper and Otto Soglow. Over time, the New Masses became narrower politically and more journalistic in its tone.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/new-masses/1938/v28n12-sep-13-1938-NM.pdf