Art Shields reports on conditions in Henderson, North Carolina.

‘A Southern Mill Town’ by Art Shields from the New Masses. Vol. 3 No. 8. December, 1927.

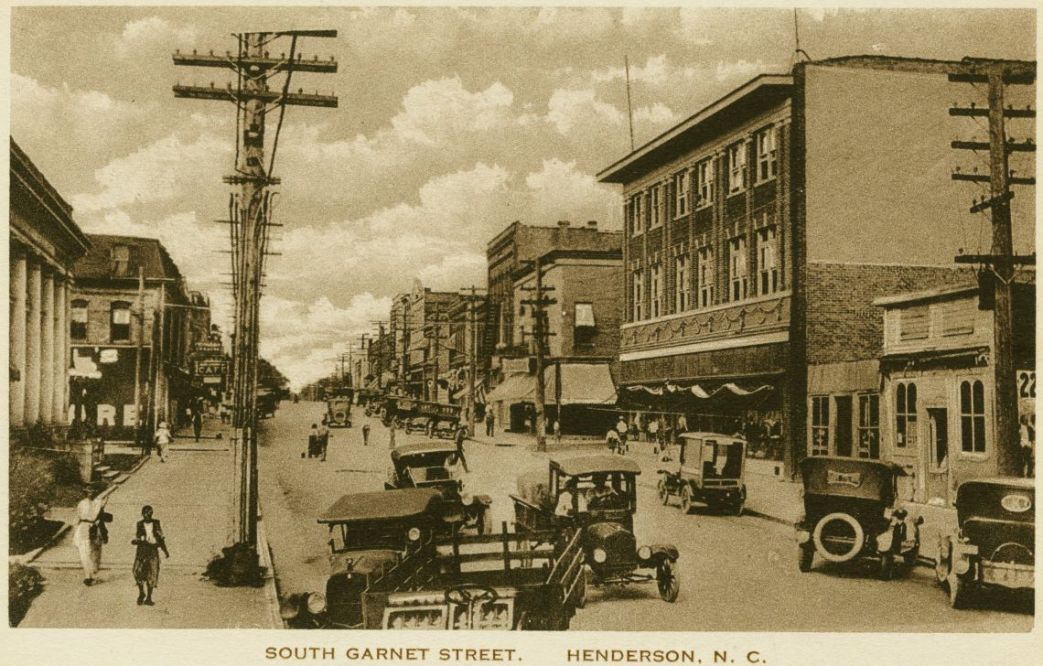

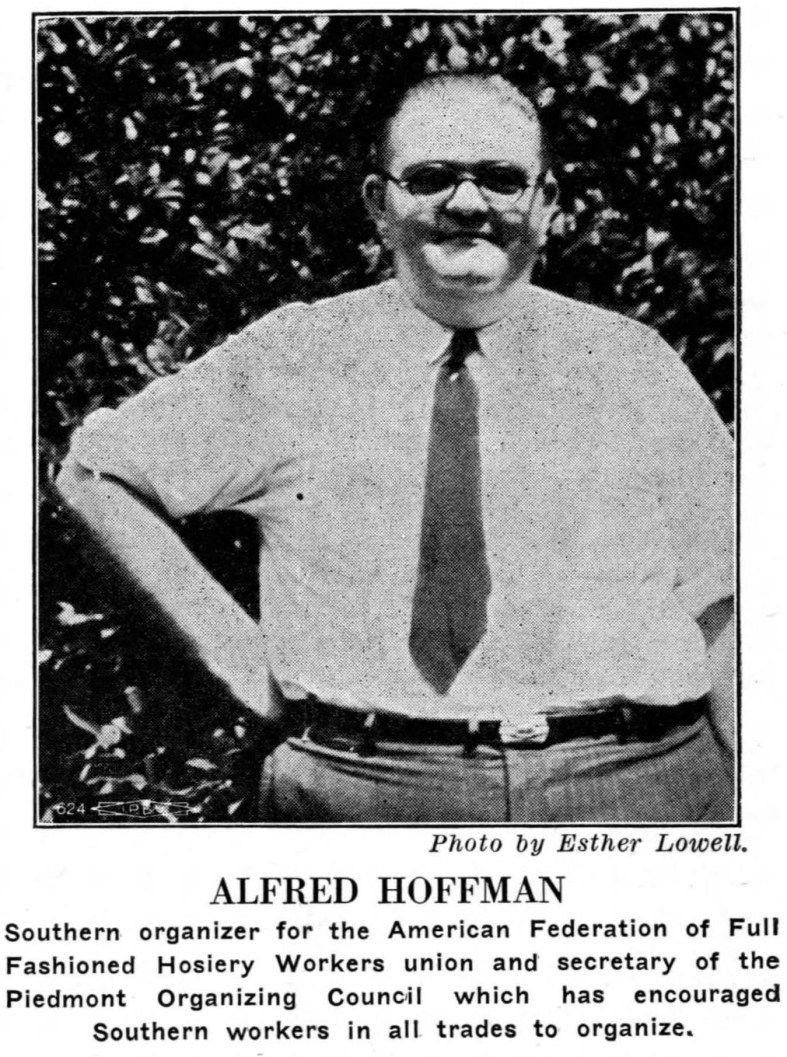

(Henderson, North Carolina is a little town 40 miles from Durham. This fall the workers of the five mills owned by the Cooper brothers demanded back the 12 per cent increase which was cut from their wages in 1924 and promised them “when conditions warranted.” The workers saw the mills running full time, day and night, and thought the time was ripe, but the mill bosses threw their petition in the waste basket. Then came the walkout, which lasted five weeks and brought Alfred Hoffman, southern organizer of the American Federation of Full-Fashioned Hosiery Workers, to the scene. He helped the strikers organize a local of the United Textile Workers, in which his own union is an autonomous unit, and aided in obtaining relief. Tobacco farmers of the surrounding country sent in vegetables and the strikers gave time to farm work. But the Coopers bought off a few leaders who led the rest astray with false promises while Hoffman was away at his union convention seeking more relief funds. Art Shields visited Henderson a few weeks after the strike ended, when the workers were realizing that the Coopers’ promises were empty ones.)

Henderson really cuts one: such misery!

I could not realize what living on a few dollars a week meant till I heard those women talking. There were three of them, in front of the Johnson store, alongside of the union organizers auto. I stepped in as they were talking to him.

They are gaunt, these factory women, gaunt and yellow-skinned. A woman of thirty-five or forty was talking. Her nose and cheekbones stuck out. There were heavy brown crows-feet under the yellow skin.

“I had only thirty-five cents in my envelope,” she was saying. “They took everything else out.”

The company deducts for wood, rent, coal, and is taking off now for groceries advanced in the early days of the strike.

“I declare,” said another woman, with little yellow rimmed spectacles, “I’ll be glad when my oldest boy is old enough to work in the mills and help me out. I just can’t live on what I’m getting.”

She complained because Miss Wardell, “that welfare woman,” comes around to see that all the children under 14 are in school.

“I want my boys to get larnin,”, she said. “I didn’t have no chance to get any myself till I got married, but I want my boys to git it. But we got to live.”

The third woman spoke up. Her last week’s pay was $3.75 before deductions. Remember that figure. You don’t find it in the books. Even Paul Blanshard’s study mentions nothing that low in North Carolina.

We drove about the town. On the “Hill” a woman came out; a winsome person in the shabbiest of cheap cotton dresses, as they all wore. With the loveliest of smiles, from a death’s-head face. It is hard to give the picture: such astonishing contrast of spirit and disease. She has T.B.

“The boy’s still havin’ night sweats,” she was telling the union organizer.

“Yes, I’m workin’ again, but I’m still with you, and I’ll stick,” she said. The skin was drawn so tightly over her bones that you’d think they would break through. She was a scarecrow of a woman, except for that lovely kind smile.

But let the smile pause and the face became ghastly. Her neck was like a bean pole.

The consumptive son is 17 or so. The county authorities dismissed him from a road gang (prison gang) when his cough became too bad. The city visitor had been promising the mother to take the boy to the sanitarium, but did nothing till the union organizer denounced her from the truck-platform at a strike meeting. Then the boy was taken away — probably to death. The little girl of seven has a hacking cough.

Mocassin Bottom is the “tough” section of the village and respectable mill workers mention it in shocked tones. A woman of 45 or 50, a mill worker all her life, told us she jes’ wouldn’t dare go through Mocassin Bottom at night.

“Would they rob you?” We asked.

“No, they wouldn’t rob you,” she said with a rising inflection that suggested more horrific mysteries. “I jes’ wouldn’t go through there.” She wished she was back in Greensboro. The village was so much better and the company would fire any “dissipated” woman.

“Ah’d move but foh mah hawg,” she said. “Mah ole Greensboro mill ud move me but the hawg ain’t big enough yet. When the hawg is biggah ah’ll ki-ill him and cu-ut him up and salt him and then Ah can move.”

A wise woman: her meat for the winter was in the big hog who was lolling in the pen in the rear.

One envies the hogs. They are positively the only well fed beings in the mill village. The men are lanky, the women are skinny, except for a few older women like the owner of this hog whose waist line has spread from much childbearing.

I heard more of Mocassin Bottom from the righteous folks on the Hill. The great wickedness of The Bottom amounted to some Saturday night and Sunday boozing, with a little gambling and prostitution.

The chief bootlegger is the proudest rebel in Mocassin Bottom. He worked in the mill long ago, and his wife until recently. He manufactures all grades of booze for workers and drinks his own — said to be rare among bootleggers. The bootlegger attends all union meetings and is a stalwart of stalwarts. He hates the Coopers who own the mill.

“What you all standing around here like a snake in the grass?” he is reported to have said to a member of the firm listening on the outskirts of a strike meeting.

The New Masses was the continuation of Workers Monthly which began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Communist Party publication, but drawing in a wide range of contributors and sympathizers. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and The New Masses began. A major left cultural magazine of the late 1920s to early 1940s, the early editors of The New Masses included Hugo Gellert, John F. Sloan, Max Eastman, Mike Gold, and Joseph Freeman. Writers included William Carlos Williams, Theodore Dreiser, John Dos Passos, Upton Sinclair, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, Dorothy Parker, Dorothy Day, John Breecher, Langston Hughes, Eugene O’Neill, Rex Stout and Ernest Hemingway, Artists included Hugo Gellert, Stuart Davis, Boardman Robinson, Wanda Gag, William Gropper and Otto Soglow. Over time, the New Masses became narrower politically and more journalistic in its tone.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/new-masses/1927/v03n08-dec-1927-New-Masses.pdf