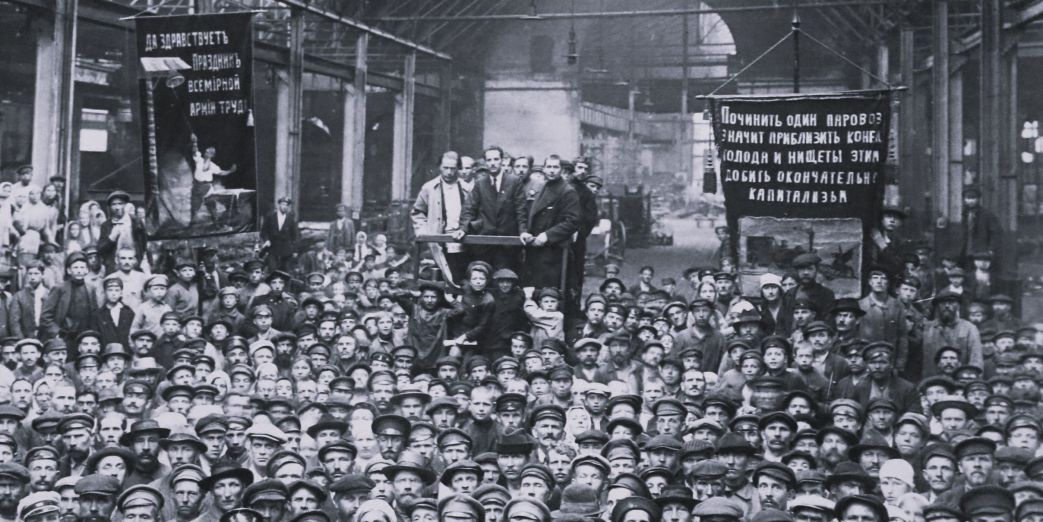

John Reed on how Shop Committees, the foundation of workers control in Soviet Russia, were formed and functioned in the first years of the Revolution.

‘Shop Committees in Soviet Russia’ by John Reed from the Voice of Labor (New York). Vol. 1 No. 1. August 15, 1919.

THE history of Labor organization in Russia is very brief. Before the 1905 Revolution no labor Unions, in the strict sense of the word, existed. The only recognized workmen’s representation was the election of a starosta, or “elder,” much as the starostas are elected in Russian villages, and even in Russian prisons, and with about as much power. In 1905, some 200,000 workmen joined the Unions. Stolypin suppressed them. Some little unions persisted, but they were finally crushed, their funds seized, their leaders sent to Siberia. After that the Unions existed half-secretly, with a membership over all Russia of about 10,000. During the war, however, all attempts at Labor organization were ruthlessly stamped out, and workmen discovered in any connection with Labor organizations were sent to the front.

Trade Unions

The-Revolution released the workers partly from this bondage, and pushed toward rapid organization. After four months of the Revolution the first conference of the Trade Unions of All-Russia was held — 200 delegates representing more that 1,400,000 workers. Two months later the membership was calculated at more than 3,000,000, according to the report of Riazonov; it is now more than double that number.

Now these Trade Unions (Professionalnye Soyuse) were industrial Unions, big Unions, which merged all the petty craft divisions into one organization. Thus in the Government gun factory at Sestroretzk, for example, all those who worked upon the manufacture of rifles — the men who forged barrels, the machinists who fitted the mechanism, the carpenters who made the stocks — were all members of the Metal Workers Union.

The Trade Unions performed an important task. Modelled on a plan which combined the best features of the French and the German Trade Unions, they reached vast numbers of workers and brought them together. But, like Trade Union movements everywhere, they were mainly concerned with the fight for shorter hours, higher wages and better conditions. They embraced the Trade Union philosophy, which leads to “agreements” and “contracts” with the employers — to the partnership of Capital and Labor. They established, for example, a system of Arbitration Commissions under Government supervision.

Why Shop Committees Were Formed

And just as in this country the mass of the workers are discontented with the reactionary and insufficient policy of the A. F. of L. — just as the policy of merely raising wages and improving conditions doesn’t lead anywhere — so in Russia Labor wasn’t satisfied. The Russian workers in the factories wanted to control industry. They wanted to control their jobs in the shops. Hampered by “agreements” and Arbitration Commissions supported by their Union officials, the workers could not act. Therefore in the shops there grew up those unique organizations, created by the Revolution itself, the Factory Shop Committees (Fabritchno-Zavodskye Komitieti). These latter are the real foundation of Workers’ Control of Industry.

The Factory Committees originated in the government munitions factories. At the outbreak of the Revolution, most of the administrators of the government factories, chiefly military officers who brutalized the workers with all the privilege of military law, ran away. Unlike the private manufacturers, these government officials had no interest in the business. The workers, in order to prevent the closing down of the factory, had to take charge of the administration. In some places, as at Sestroretzk, this meant taking charge of the town also. And these government plants were run with such inefficiency, so much corruption, that the Workers’ Committee, although it raised wages, shortened hours, and hired more hands, actually increased production and lowered expenses — at the same time completing new buildings begun by dishonest contractors, constructing a fine new hospital, and giving the town its first sewerage system. With these government plants the Factory Shop Committees had a comparatively easy time. For a long time after the Revolution there was no authority to question the authority of the workers, and finally when the Kerensky government began to interfere, the workers had complete control. Working as they were on munitions, with standing orders, there was no excuse for closing down, and in fuel and raw materials the government itself supplied them. Although many times under the inefficient Kerensky government the government shop committees had to send their delegates to Baku to buy oil, to Kharkov for coal, and to Siberia for iron.

Shop Committees at Work

From Sestroretzk the Shop Committee spread like wild-fire to other government shops — then to private establishments working on government orders, then to private industries, and finally to the factories which were closed down at the beginning of the Revolution.

First the Movement was confined to Petrograd, but soon it began to spread over all Russia, and just before the November Revolution took place the first All-Russian Congress of Factory Shop Committees. At the present time, representatives of the Factory Shop Committees and representatives of the Trade Unions make up the Department of Labor of the new government, and compose the Council of Workers’ Control.

The first Committees in the private factories were mainly engaged in keeping the industry going, in the face of lack of coal, of raw materials, and especially, the sabotage of the owners and the administrative force, who wanted to shut down. It was a question of life and death to the workers. The newly-formed Shop Committees were forced to find out how many orders the factory had, how much fuel and raw material were on hand, what was the income from the business — in order to determine the wages that could be paid — and to control itself the discipline of the workers, and the hiring and discharging of men. In factories which the owners insisted could not keep open, the workers were forced to take charge themselves, and run the business as well as they could.

Some of the experiments were very interesting. For example, there was a cotton factory in Novgorod which was abandoned by its owners. The workers — inexperienced in administration — took charge. The first thing they did was to manufacture enough cloth for their own needs, and then for the needs of the other workers in Novgorod. After that the Shop Committee sent men out to factories in other cities, offering to exchange cotton cloth for other articles they needed — shoes, implements; they exchanged cloth for bread with the peasants; and finally they began to take orders from commercial houses. For their raw material they had to send men south to the cotton growing country, and then with the Railroad Workers’ Union they had to pay with cloth for the transportation of the cotton. So with fuel from the coal mines of the Don.

In the great private industries which remained open, the Factory Shop Committees appointed delegates to confer with the administration about: getting fuel, raw material, and even orders. They had to keep account of all that came into the factory, and all that went out. They made a valuation of the entire plant, so as to find out how much the factory was worth, how much stock was held, what the profits were. Everywhere the workers’ greatest difficulty was with the owners, who concealed profits, refused orders, and tried in every way to destroy the efficiency of the plant, so as to discredit the workers’ organizations. All counterrevolutionary or anti-democratic engineers, clerks, foremen, etc., were discharged by the Factory Shop Committees, nor could they enter any other factory without the recommendation of the Factory Shop Committee of their preceding place of employment.

Workers were required to join the Union before they were hired, and the Factory Shop Committee supervised the carrying out of all Union scales and regulations.

The Fight Against the Committees

The fight by the capitalists against these Factory Shop Committees was extremely bitter. Their work was hindered at every step. The most extravagant lies have been published in the capitalist press about “lazy workmen” who spent all their time in talking when they should be working— while as a matter of fact the Factory Shop Committees usually had to work eighteen hours a day; about the enormous size of the Committees — while for example at Putilov Works, the largest factory in Petrograd, employing about 40,000 men, the Central Factory Shop Committee, representing eleven departments and 46 shops, consisted of twenty-two men. Even Skobelev, “Socialist” Minister of Labor under the Kerensky government, issued an order in the first part of September that the Factory Shop Committees should only meet “after working hours,” and no longer receive wages for their time on Committee business. As a matter of fact, the Factory Shop Committees were all that kept Russian industry from complete disintegration during the days of the Kerensky Government. Thus the new Russian industrial order was born of necessity.

Each Factory Shop Committee had five departments: Production and Distribution, Fuel, Raw Materials, Technical Organization of the Industry, and Demobilization (or changing from a war to a peace basis). In each district, all the factories of one industry combined to send two delegates to a district council, and each district council sent one delegate to the city council — which in turn had its delegates in the All-Russian Council, in the Central Committee of the Trade Unions, and in the Soviet.

Not all workmen were Union workmen in Russia; but every factory worker had to be represented in the Factory Shop Committee. And the Shop Committee forced its members to join their Unions.

Today the Unions stabilize wages and conditions throughout each industry, and these Union regulations are put into effect by the Shop Committees in each shop. The Union determines the scale and the hours of labor; the Shop Committees control production in the factories, requisition fuel and raw material, and arrange with the Railway workers and the Co-operatives for distribution. But equally important, the Shop Committees, who control the shops, and are the direct representatives of the workers on the job, are able to check up the actions of the Trade Unions and to control the Trade Union Officials.

The entire economic life of Soviet Russia is now managed by the Supreme Council of Public Economy, which is made up of representatives of the Trade Unions, the Factory Shop Committees, the peasant’s Land Committees, and the organizations of technical experts — such as engineers, chemists, etc.

As all industry is the property of the Soviet Government, in which only workers can vote, Russian Labor is supreme.

The Voice of Labor was started by John Reed and Ben Gitlow after the left Louis Fraina’s Revolutionary Age in the Summer of 1919 over disagreements over when to found, and the clandestine nature of, the new Communist Party. Reed and Gitlow formed the Labor Committee of the National Left Wing to intervene in the Socialist Party’s convention, eventually forming the Communist Labor Party, while Fraina became the first Chair of the Communist Party of America. The Voice of Labor’s intent was to intervene in the debate within the Socialist Party begun in the war and accelerated by the Bolshevik Revolution. The Voice of Labor became, for a time, the paper of the CLP. The VOL ran for about a year until July, 1920.

PDF of full issue: https://archive.org/download/v1n1-aug-15-1919-voice-of-labor-ocr/v1n1-aug-15-1919-voice-of-labor-ocr_text.pdf