Harrison George, himself a former political prisoner–a wobbly who became a founding member of the Communist Labor Party while in Leavenworth, pays tribute to ‘flaming souled type-setter’ Albert Parsons and provides context for the events of Haymarket.

‘The Voice of May Day’ by Harrison George from the Daily Worker Saturday Supplement. Vol. 2 No. 35. April 26, 1924.

“There will be a time when our silence will be more powerful than the voices you strangle today!”- August Spies on the scaffold.

Capitalism is insanity, its voices come from madman throats, the hysterical shrieks of homicide, the moans of the wounded, the mutterings of masses in despair… But clear and beautiful with the beauty of relentless purpose, there arises above all the discord of the voices of those workers who would be free, voices which inspire and direct the struggle; voices which call to arms.

Because these voices were raised on May First, 1886, four workers were strangled to death in the Cook County Jail at Chicago. But tho these workers were strangled and the years have fled, their voices on this First of May, 1924, ring round the world!

What did May First mean in 1886? Whose were these voices? In what cause were they raised? Who strangled them?

The N.L.U. Sells Out.

For twenty years, since the Eight Hour Leagues joined in the first nation wide movement in the National Labor Union formed in 1886, labor had fought futilely and pitifully for an eight-hour day. But the N.L.U. was an undefined entity, directed by simple-minded or self-seeking leaders. The first begged scornful capitalist politicians for legislation, the latter sold out the workers. President Johnson lied to them, and tho eight-hour laws were passed in six states, they were never enforced. When this fraud was protested one governor answered that, “Every law is obligatory by its own nature and can derive no additional force from any act of mine.” The sacred “right of contract” was injected into the laws by providing that only “when the contract was silent” on the matter of hours did the eight-hour provision become effective. Workers had to sign any contract presented it they wanted work–and there were hordes of unemployed. The soldiers who had fought to free the chattel slaves had merely created a fairly homogeneous class of wage slaves and found themselves among it, unemployed and starving.

With the inspiring exception of the successful strike of 100,000 building 1872, economic depression discouraged strikes and, naturally, the workers turned to politics; and, just as naturally, the theoretically ignorant, the organizationally mixed, divergent and inexperienced workers failed to accomplish anything. Even the so-called labor party formally started by the N.L.U. in 1872 was killed in the cradle by the treacherous leaders of the national trade unions withdrawing their forces leaving nothing but an ideal, a shadow; for the N.L.U. was a hopelessly mixed body of Eight-hour leagues, co-operatives, local unions, assemblies and national trade unions.

Play Capitalist Politics.

But, then as now, the “no politics” of the trade union leaders transformed itself into capitalist politics: their spokesman, H.J. Walls of the Iron Molders, who said in 1873 that his union withdrew from the N.L.U. because the N.L.U. had “become a political organ,” himself played the game of capitalist politics SO well that he was appointed by the Republicans as Commissioner of Labor for Ohio in 1877.

It is necessary to understand the immaturity of the labor movement at that time, as well as the savagery need in representing its first unscientific efforts to ease its burden only a little, to comprehend the great collision of social forces on the First of May, 1886, and how those who lead the workers’ struggle gave their lives to advance, if only by a step, the interests of the proletariat.

The 70’s were dark years for labor. Unemployment sent not only men by the tens of thousands to tramping the country, but women and girls. The unions were wrecked, wages were but a disguise for starvation, blood flowed at the least sign of resistance, the Pinkerton gunman and the murderous militia held back the blind rebellion.

In March, 1876, Albert R. Parsons, who later died on the scaffold, joined the Social-Democratic Party, which became a part of the First International, then crumbling in Europe but guided by Marxists in America. How this flaming souled type-setter, then a member of Typographical Union 16, was influenced by Marxian thought may be seen by comparing the following instruction issued by the International as guidance to its Chicago section, with Parsons own expressions: Said the International:

“The trade union is the cradle of the labor movement, for working people naturally turn first to that which affects their daily life, and they consequently combine first by trade. It therefore becomes the duty of the members of the International not merely to assist the existing unions and to internationalize them, but also to establish new ones. Economic conditions were driving the trade union from the economic to the political struggle against the propertied classes.”

The Social Democratic Party faded into the Socialist Labor Party, which nominated Parsons for president in 1879. But we find Parsons writing from prison in 1886, in the same language as that used today by the Communists in the unions:

“Examination of the class struggle demonstrate that the eight-hour movement was doomed to defeat. But the International gave its support to it for two reasons. First, because it was a class movement, therefore historical, evolutionary and necessary; secondly, because we did not choose to stand aloof and be misunderstood by our fellow-workers. We therefore gave it all aid. I was regularly accredited by the Central Labor Union, representing 20,000 organized workmen in Chicago, to assist in organization of unions and do all in my power for the eight-hour movement.”

We can understand why, tho the “International”, Parsons here refers to probably was the so called “Anarchist International” then following the First International into oblivion, the Marxian revolutionists claim Parsons and his fellows as their own.

The traditions of the 70’s were working in the struggle of 1886. The wave of general strikes of 1877 was witnessed by Parsons and the rest.

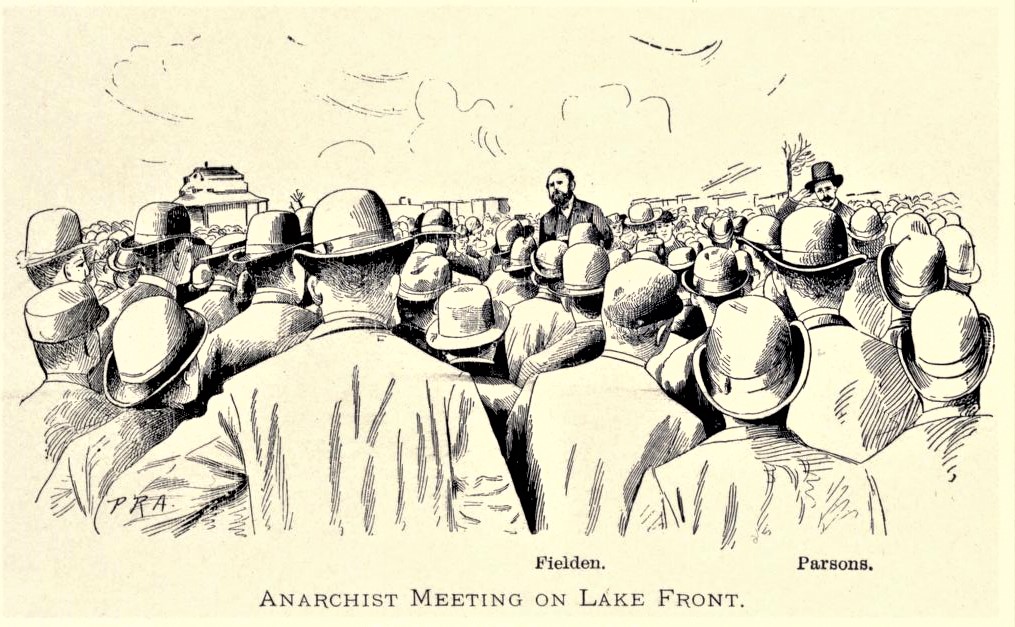

Battles were fought by workers against murderous Pinkertons and, in Pittsburgh, workers enraged by slaughter of thirty strikers by the militia, first besieged the soldiery then drove them from the city. In St. Louis a workers committee ruled the city for a week. At Chicago the police clubbed and shot workers wantonly. The Militia fired into crowds without compunction. Parsons addressed meetings of 40,000. He was then President of the Chicago Labor Assembly–its first president. In 1879, when Parsons’ group called for celebration of the Paris Commune, 60,000 people responded.

“Now, men, I warn you, that if you do not go to work at once for a $1.50 a day, the military will be sent here to compel you.” So said the Sheriff of Cook County to striking workers in 1885, and this exemplifies the reckless repression used by the capitalists in those years. “Such treatment,” says Parsons, “Would of necessity drive the workingmen to employ the same method.” It would.

Groups of workers, armed for self-defense, sprung up everywhere. The Sunday before May Day in 1886, Parsons spoke at Cincinnati at a great eight-hour demonstration. Thousands marched in a parade headed by two or three organized companies of workers armed with Winchester rifles under the red flag. A rising tide…!

The reason was that both national labor bodies had, in 1884, declared that on and after May 1, 1886, eight hours should constitute a day’s work and that a general strike should demand it. Enthusiasm reigned, 600,000 poured into the unions in the first four months of 1886. Gompers in the old Federation was opposed, and Powderly of the Knights of Labor was indifferent; but workers everywhere believe and Parsons and his comrades were with the masses.

The great strike broke on May Day 1886. Parsons says 360,000 struck, others say 200,000; 40,000 in Chicago. May 3rd, police fired on strikers, killing one, wounding several. At a protest meeting next day at the Haymarket, some unknown person threw a bomb, when the police attacked the crowd, killing seven policemen.

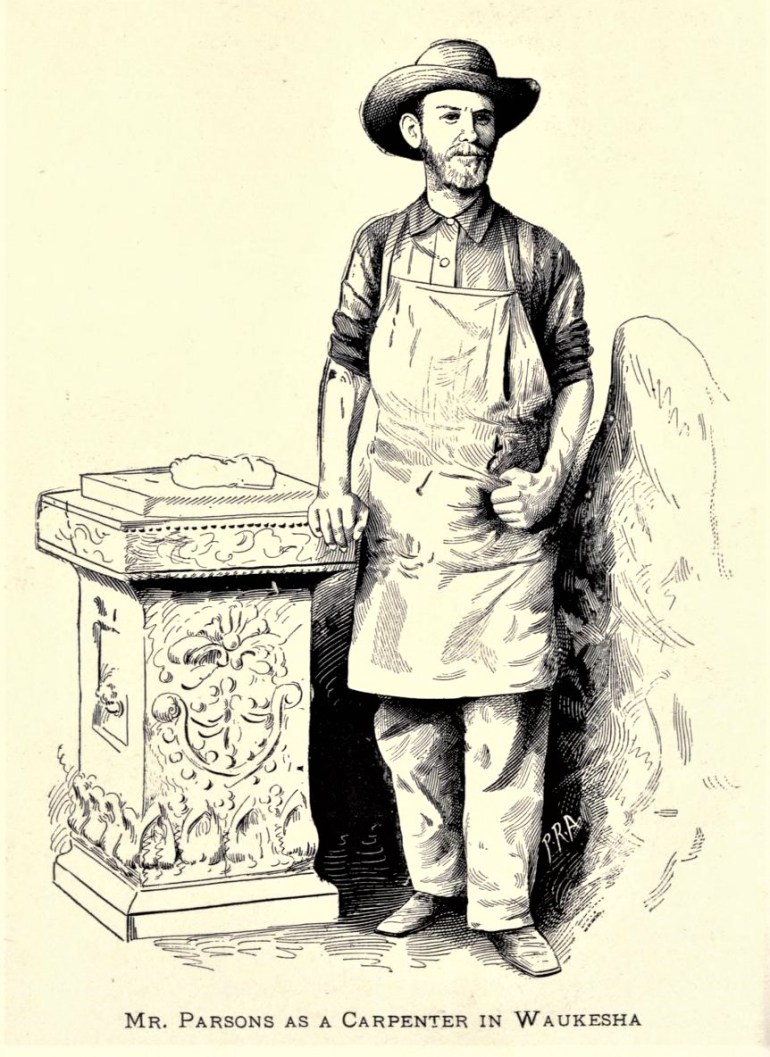

Tho the murder of workers was an everyday occurrence, the press suddenly went frantic over the dead police; the Chicago Tribune and Times drove the “better classes” into frenzy. Police “found” bombs everywhere. Tho not one of the seven men who were arrested, or Parsons, who surrendered voluntarily, had been at the meeting when the bomb was thrown, all were pronounced guilty after a farcical trial. Three were commuted and pardoned after seven years. Louis Ling robbed the hangmen. Albert R. Parsons, August Spies, Adolph Fischer and George Engel were hanged on November 11, 1887.

From under the hood on that morning came the cry of Parsons, cut short by the crash of the death trap: “Will I be allowed to speak, O men of America? Let me speak, Sheriff! Let the voice of the people be heard! Oh…!”

Sleep, my murdered Comrade! Sleep! Your life, your words, your deeds, your death, are today being told around the world. Your tongue was silenced, but your voice, the voice of the proletariat is raised today in every land, in every clime–in the chant of The Internationale. The flags they march under are red, my comrade, and–led by the Communist International–they march to victory!

The Daily Worker began in 1924 and was published in New York City by the Communist Party US and its predecessor organizations. Among the most long-lasting and important left publications in US history, it had a circulation of 35,000 at its peak. The Daily Worker came from The Ohio Socialist, published by the Left Wing-dominated Socialist Party of Ohio in Cleveland from 1917 to November 1919, when it became became The Toiler, paper of the Communist Labor Party. In December 1921 the above-ground Workers Party of America merged the Toiler with the paper Workers Council to found The Worker, which became The Daily Worker beginning January 13, 1924.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/dailyworker/1924/v02a-n035-supplement-apr-26-1924-DW-LOC.pdf