Albert Parsons’ reports from agitational tours back home to his Chicago-based ‘Alarm’ newspaper are goldmines of social history. This is no exception as Parsons travels in the summer of 1885 through Kansas, Missouri, and Nebraska spreading the word of working class emancipation.

‘The Gathering Storm’ by Albert R. Parson from The Alarm. No. 27. July 25, 1885.

THE REVOLT! THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE SOCIAL REVOLUTION IN THE FAR WEST. An Agitation Trip Through Missouri, Kansas, and Nebraska by Comrade Parsons. THE SOCIAL STATUS OF THE WORKING PEOPLE AND THEIR VIEWS ON THE SITUATION. Labor Everywhere Preparing for Revolt Against the Private Property Beast. THE POVERTY, MISERY AND DEGRADATION OF THE WAGE-SLAVES OF AMERICA. Many Groups of the International Working People’s Association Organized. THE GATHERING STORM.

COMRADES: After my visit to Ottawa, Kan., on the Fourth of July last, where I delivered an address to the working people of that section on the “Social Revolution,” which was received by them with unbounded enthusiasm, I on Monday, by way of Kansas City, made my way to Topeka, a city of 25,000 people and Capital of the State of Kansas. I visited the local assembly of the Knights of Labor, which has a very large membership here, and made a short talk to them, when they resolved to. hold an open-air meeting on the Thursday following, and invited me to address it. In Topeka I found such stalwart champions of revolutionary Socialism as Comrades Henry, Blakesley, Whiteley, Vrooman, Bradley, and others — intelligent and fearless young men who cry out against and spare not the infamies of the capitalistic system.

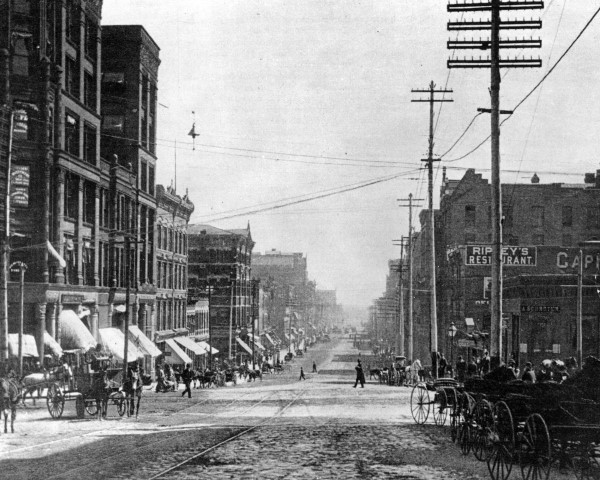

On Tuesday I returned to Kansas City and spoke at a mass meeting of the working people at that place held on Thursday, July 7, which had been arranged by Comrades Bestman, Schwab, and others. The meeting was held in Armory hall, where at the hour named, though the weather was oppressively hot, fully 400 persons were assembled. They remained for over two hours while I discussed the principles of Socialism, at the close of which circulars, pamphlets, and copies of the Alarm were freely distributed, and much satisfaction was expressed by those present with what they had heard. On the night following an open-air meeting was held on Market square, situated in the center of the city upon one of the main thoroughfares, where an audience of fully 1,500 persons gathered around the speaker. The sentiments expressed were received with applause and unanimous approbation, and much progress was made.

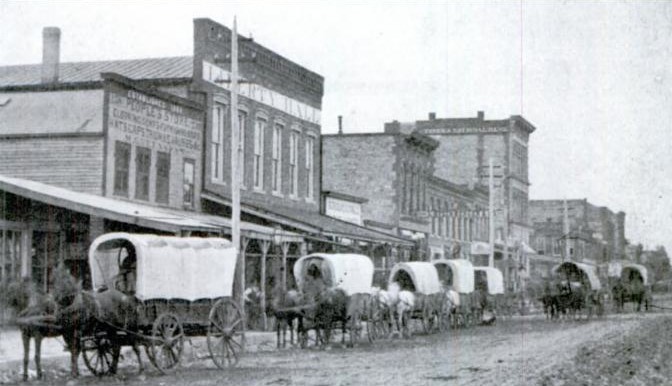

On Thursday I returned to Topeka. I found the columns of the capitalistic papers filled with notices of our proposed meeting. At 8 o’clock p.m. a crowd of over 1,500 people, mostly workingmen and women, gathered on the street corner of Kansas avenue and Sixth street, where an express wagon was placed in the middle of the street for the speakers’ stand. The crowd listened for three hours with every sign of approbation, and a large American Group and several subscribers for the Alarm was the result. The capitalistic papers denounced us the next day, and threatened your humble speaker with lynching, but it is far more probable that the workingmen of Topeka would lynch the capitalists of Topeka than to allow themselves to be mobbed by them.

The next day I departed for St. Joseph, Mo., a beautiful and very wealthy city of 50,000 inhabitants, where Comrades Christ, Mostler, Nusser, and others had prepared a mass-meeting in Turner hall on Saturday. There had been considerable talk of my advent in the columns of the capitalistic press of that city, and many were the remarks, favorable and otherwise, made about the appearance in their city of Parsons from Chicago. As was to be expected, the conservative workingmen, who profess to have faith in the curative powers of the ballot-box, strikes, arbitration, etc., were loud in their denunciations of the revolutionary Socialists, and they were at great pains to have the public understand that the Knights of Labor was an organization which had nothing whatever to do with these “Communists,” etc. Well, at the hour named the largest audience ever brought together in St. Joseph on such an occasion were gathered in the Turner hall, where those who could not get seats stood in the sweltering weather of a hot July day for over three hours, attentively listening to and applauding the utterances of the speaker. The meeting created a profound impression, and was the talk of the city next day. On the evening following I spoke to a large audience in the same city, in Knights of Labor hall, and spoke again on Monday evening before an assembly of Knights of Labor, when a resolution was unanimously adopted inviting me to address, at my earliest convenience, an open-air meeting under the auspices of the Knights of Labor, they paying the expenses, etc. When it is considered that the capitalistic press (there are three morning dailies in St. Joseph) were out in editorials every day showing up the fallacies of Socialism, and stating that such doctrines have no followers in that city, and that the Knights of Labor were especially hostile to all revolutionary teachings, and the attitude of the Knights of Labor before the meetings were held, some idea can be formed of the tremendous effect the agitation produced, when the men and organizations which were loudly denouncing us are now heart and hand with us, and have arranged a mass-meeting for me to address. It is satisfaction enough to know that three meetings held in St. Joseph created a deep impression, and have been the talk of the place since.

Monday night, at 1 o’clock, I took the train for Omaha, Neb. Comrades Ruhe, Kretschmer, Kopp, and others had arranged a mass-meeting in Kessinger’s large hall for Tuesday evening. It was sweltering weather, and yet the hall was crowded with an attentive audience, filled with about 500 persons who remained and with approval and satisfaction listened to a two hours’ speech. Several names were taken for the formation of an American Group of the International, and many copies of the Alarm sold. It was announced that an open-air meeting would be held the following evening in Jefferson park. Owing to the lack of time to advertise, not over 500 persons were present. I spoke to them for two hours, and took several names for the formation of an American Group.

On Friday I returned to Kansas City, where I found letters inviting me to speak in Scammonville, Weir City, and Pittsburg, in the southern part of the State of Kansas. Large and enthusiastic mass-meetings were held in these places. I spoke in Scammonville Sunday afternoon, in Weir City the following evening, and Pittsburg on Monday night. Large American Groups were formed in the two former places.

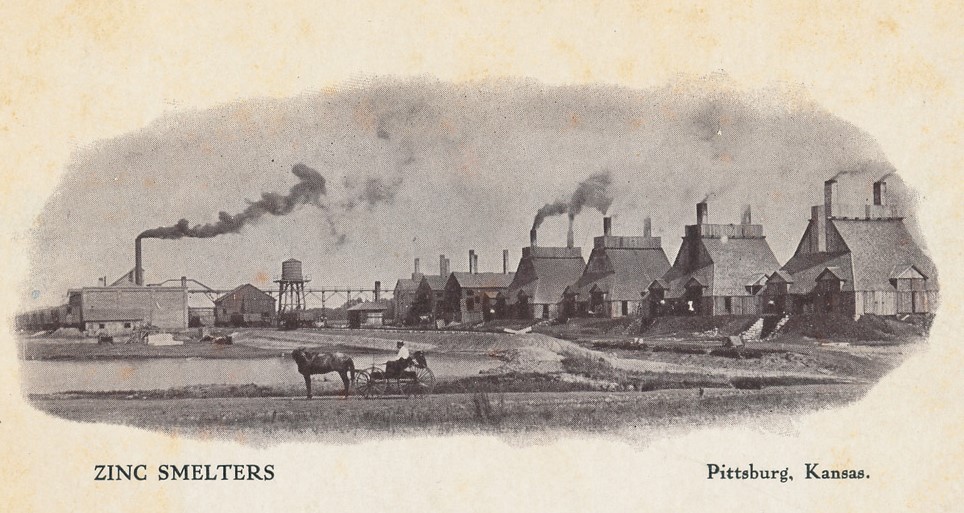

Let me describe to you the condition of the wage-slaves in Pittsburg. It is a place of about 4,000 inhabitants, and has several coal mines and smelting works. The mine-owners will not employ any person who belongs to a labor organization or who takes and reads a labor paper. The coal syndicate owns a truck store, in which its employes are compelled to trade under penalty of losing their bread. It owns nearly all of the houses, and in all matters of work and social conduct its commands must be strictly obeyed. The capitalistic Czars of that section hold absolute dominion over their wage-slaves. It was” thought to be rather risky business to beard the lion in his den by holding a labor meeting within the domain of these capitalistic autocrats, but nothing daunted, our fearless comrades, John Schrumm and John McLaughlin, of Scammonville, accompanied me and we got out hand-bills announcing the meeting on the principal and only business street, just opposite the truck store of the coal company. A table was procured and served as a platform. Comrade John McLaughlin, editor of the Labor Journal, mounted it and spoke for about half an hour, when I was introduced to the vast audience which had assembled and was standing in the street. Of course, as you may suppose, we showed up in the strongest terms we could employ the fearful ravages the “Beast of Property” was making upon the lives and liberties of the propertyless class. The crowd of men and women remained for three hours and cheered our utterances to the echo. The affair created a profound sensation and was the talk next day of every one in the town. Passing by the door of the general offices of the coal syndicate next morning, in company with Comrades McLaughlin and Alfred Wilson, on accosting a man standing in the door, he replied : “Go to h — l! I don’t speak to such as you,” and when he had passed a few steps, he added: “You are nothing but a lot of sons of b — s anyway!” He was invited to step outside and take out any satisfaction he might desire by Comrade McLaughlin, but he said nothing further and we moved on. The truck store of this town is devouring the other business men, and they all feel bitterly hostile toward it. Great good was done by our meeting in this place.

The capitalistic press state that there are over 12,000 unemployed people in Kansas City, which is a place of about 130,000 inhabitants; that there are 5,000 in Omaha and about the same number in St. Joseph out of work. The same holds good in Topeka and Council Bluffs, and in all the smaller towns large numbers are out of work. I saw tramps on the wayside everywhere, and at Nebraska City junction, on the Kansas City, St. Joe & Council Bluffs railroad, on the Missouri river, in Iowa, I read the following printed on cloth in large letters and tacked up securely on the walls of the railroad station:

Tramps Are Hereby Notified to Move on.

On my return to Kansas City from my trip to the mining regions I found an invitation to return and address an open-air meeting in St. Joseph on Thursday evening, July 23. I spoke here in Kansas City to a large mass-meeting of workingmen, mostly “tramps,” on Market square. I will speak at the same place and go to St. Joseph, and thence back to Chicago.

This trip has been productive of much good. Eight American Groups of the International Working Peoples’ Association have been formed, and fully 20,000 wage-slaves have for the first time heard the gospel of “Liberty, Fraternity, and Equality.” In every place there were large and earnest meetings, with the most satisfactory results. The working people thirst for the truths of Socialism and welcome their utterance with shouts of delight. It only lacks organization and preparation, and the time for the social revolt is at hand. Their miseries have become unendurable, and their necessities will soon compel them to act, whether they are prepared or not. Let us then redouble our efforts and make ready for the inevitable. Let us strain every nerve to awaken the people to the dangers of the coming storm between the propertied and the propertyless classes of America. To this work let our lives be devoted. Vive la Revolution Sociale!

The Alarm was an extremely important paper at a momentous moment in the history of the US and international workers’ movement. The Alarm was the paper of the International Working People’s Association produced weekly in Chicago and edited by Albert Parsons. The IWPA was formed by anarchists and social revolutionists who left the Socialist Labor Party in 1883 led by Johann Most who had recently arrived in the States. The SLP was then dominated by German-speaking Lassalleans focused on electoral work, and a smaller group of Marxists largely focused on craft unions. In the immigrant slums of proletarian Chicago, neither were as appealing as the city’s Lehr-und-Wehr Vereine (Education and Defense Societies) which armed and trained themselves for the class war. With 5000 members by the mid-1880s, the IWPA quickly far outgrew the SLP, and signified the larger dominance of anarchism on radical thought in that decade. The Alarm first appeared on October 4, 1884, one of eight IWPA papers that formed, but the only one in English. Parsons was formerly the assistant-editor of the SLP’s ‘People’ newspaper and a pioneer member of the American Typographical Union. By early 1886 Alarm claimed a run of 3000, while the other Chicago IWPA papers, the daily German Arbeiter-Zeitung (Workers’ Newspaper) edited by August Spies and weeklies Der Vorbote (The Harbinger) had between 7-8000 each, while the weekly Der Fackel (The Torch) ran 12000 copies an issue. A Czech-language weekly Budoucnost (The Future) was also produced. Parsons, assisted by Lizzie Holmes and his wife Lucy Parsons, issued a militant working-class paper. The Alarm was incendiary in its language, literally. Along with openly advocating the use of force, The Alarm published bomb-making instructions. Suppressed immediately after May 4, 1886, the last issue edited by Parson was April 24. On November 5, 1887, one week before Parson’s execution, The Alarm was relaunched by Dyer Lum but only lasted half a year. Restarted again in 1888, The Alarm finally ended in February 1889. The Alarm is a crucial resource to understanding the rise of anarchism in the US and the world of Haymarket and one of the most radical eras in US working class history.

PDF of full issue: https://dds.crl.edu/item/54013