Among the dozens of the social theater groups to emerge in the 1930s, the Theatre Union strove for the highest artistic quality, and unlike many other troupes, used professional actors and writers. Perhaps their best known play was Stevedore, about Black waterfront workers.

‘Meet the Theatre Union’ by Emery Norhrup from New Theatre. Vol. 1 No. 3. February, 1934.

THE Theatre Union was organized with two central concepts: 1. That there was an immediate need for a workers’ theatre to produce plays with working class propaganda content. 2. That such a theatre must compete in technical skill and artistic attraction with the Broadway theatre and the Hollywood movie; and yet, be so cheap in price that the average workers, who cannot lay out $2.20 for a Broadway seat, could attend.

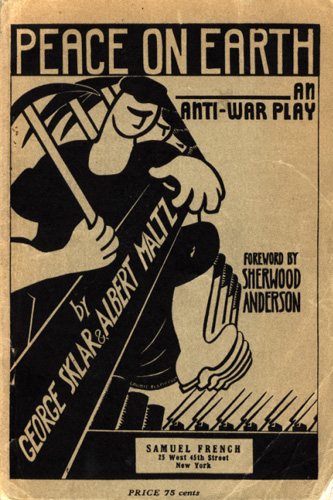

The original nucleus of the theatre included playwrights, technicians, some people with business and executive experience, and actors. A few scripts were at hand which the Theatre Union considered suitable for production; and others were being written by writers who knew what the Theatre Union stood for. Really good manuscripts that combine a clear grasp of social conflicts with tense dramatic writing are, undoubtedly, going to be hard to find. In Peace On Earth, by George Sklar and Albert Maltz, however, the Theatre Union was fortunate in getting one of the rare plays that combines, both requirements.

The problem of organizing a suitable acting company was artistic standards, the Theatre not easy. Bent upon the highest Union found at once that it would have to call upon professional actors. A nucleus of these, already conscious of class line-ups, had been drawn into the theatre through meetings, discussions, and active participation in organizing, getting members, and raising funds. The play, however, called for 40 actors. Equity regulations made it impossible to use half professional, half amateur actors. It was obvious, then, that if the Theatre Union was determined to put on a thoroughly competent performance, it would have to fill some roles with actors chosen solely for their ability.

ONCE the casting began, however, it was surprising how many good Broadway actors applied for parts who were honestly eager to join a theatre devoted to what they called “social drama” or “propaganda drama.” Many of them were disillusioned with Broadway; many felt bitterly their insecure economic condition under the Broadway real-estate regime; many were hunting for some new outlet that would enable them to make serious use of their talent. The actors who play the leading roles in Peace On Earth are, with few exceptions, people either definitely allied with the cause of a workers’ theatre from the start, or the more thoughtful actors who had begun to rebel.

Among the younger actors, nearly all of them are class-conscious or “sympathetic.” The Earth” extras are members of the Workers Ex-Servicemen’s League.

At first some three or four of the cast, more removed from contact with the labor movement, presented difficulties. They balked at certain lines and certain bits of action. They talked of “soap box.”

The first public performances of Peace On Earth changed all this. The parts labeled “soap box” suddenly stood out as the most vital moments of the play. The audience of workers warmed under them; stood up, cheered, and applauded. At these moments above all others the air became electric with that peculiar tie between player and audience which creates the supreme moments of the theatre.

BACKSACKSTAGE nobody talks about “soap box” anymore these days. In the eight weeks that Peace On Earth has been running a change has come over the cast. Those who were close to the Theatre Union have blossomed under the inspiring warmth of the audience. They have grown surer of themselves, bolder, and better actors. The others have begun to think.

What is better, they have begun to read. John Strachey’s Coming Struggle for Power is circulating up and down the dressing room aisle. Almost every day new articles dealing with war, with workers, with social drama and literature appear on the bulletin board. Some of the W.E.S.L. men are doing a rushing business in ten cent pamphlets on working class problems. Actors have begun digging into Marxist literature. Almost anytime before, between and after plays you will find the aisle full of arguing actors; argument never lets up: the new deal, the working class movement, the Soviet Union, profits, the future of the drama, the Negro problem, wages, and “recovery.” A radio in one of the dressing rooms plunged the whole cast into a tumult of debate during President Roosevelt’s opening harangue to Congress. One of the most recalcitrant actors is now reading avidly to find out what the social world he lives in is like. A W.E.S.L. is his literary guide.

Out of the 40 there are now, besides the corps of worker ex- servicemen, 12 others who know their economics. They work like leaven among the group; a gradual, irresistible process of enlightenment. Millicent Green, for instance, says: “I’ve always felt that the theatre should be a means of political and social expression. This is the first play in which I had a chance to express that feeling myself. No other play ever did it. A few plays attempted it with a slightly satirical approach; but no other play involve both the actors and the audience like Peace On Earth.

“FOR some years now I have wanted to contribute to the social struggle. I’ve often talked to my friend Eleanor Curtis on how I could do it. I cannot, like Eleanor, go out and talk on the street corner. I cannot type or write. But I can act. Now for the first time I feel that I can contribute in the way most natural for me to contribute–through my acting.”

An amusing commentary on what has happened to the actors is the news that the man who plays John Andrews, the munitions manufacturer, is reading the New Masses line for line. And the bishop is proud of every hiss he draws when he cries: “If Jesus Christ were walking the earth today he would be the first to join the fight.”

The development of an excellent young actor for a workers’ theatre is seen in the progress of Fred Herrick, a member of the cast in Peace On Earth. Young Herrick first acted in We the People, by Elmer Rice. A few months later he attracted attention as the unemployed youth in the Theatre Collective’s revival of 1931 by Paul and Claire Sifton. He is now doing some interesting work playing three roles in Peace On Earth.

But better than any amount of arguing, better than any contact with advanced members of the cast, has been the audience. Night after night an audience almost wholly of working class elements crowds into the old Civic Repertory Theatre. That audience knows what it likes. It comes to the Theatre with eagerness and freshness; it is un- abashed and vigorous in its applause, boos, hisses, and cheers. The actors are crazy about that audience. “I’ve never played to an audience like that before in my life,” says Robert Keith, who has been a lead in many Broadway plays. “These are the people who should make up the audience of the theatre. They are honest; they have feeling. To play before them makes the actor feel again that the theatre is a great art.

SINCE January the Theatre Union has opened its studio for actors. One group is rehearsing scenes from The Sailors of Catarro, by Friedrich Wolf; and together with discussion of technique there is sandwiched in considerable debate on social democracy and dictatorship of the proletariat. Another group is doing scenes from The Third Parade, by Charles Walker and Paul Peters; and inevitably the role of the government in the attack on the bonus marchers of 1931 must be treated also. A third studio class is studying acting technique, without which theatre can hope to achieve telling propaganda.

The improvisation method introduced from the Soviet Union by the Group Theatre is being used in these technical studies. The Theatre Union, however, in applying this method to proletarian material, has given it a new meaning. Headlines out of the working class press are dramatized; and in this way the actors are made increasingly aware of what type of material the Theatre Union will deal with and how in their acting they can meet the requirements of this material.

Out of this studio will come the nucleus of what the Theatre Union hopes one day to have as its permanent acting company, a company which will have a hand in the management of the theatre. As yet. however, financial obstacles prevent the Theatre Union from having a permanent company. The next play, for example, may be the Negro play Stevedore which would require, in the main, Negro actors and only a few whites. The studio is meanwhile doing fruitful work with a large group of Broadway actors who will more clearly understand the role of the theatre and the propaganda play in America; and who will prefer, when there is a part for them, to play with a workers’ theatre rather than in a commercial Broadway play.

The New Theater continued Workers Theater. Workers Theater began in New York City in 1931 as the publication of The Workers Laboratory Theater collective, an agitprop group associated with Workers International Relief, becoming the League of Workers Theaters, section of the International Union of Revolutionary Theater of the Comintern. The rough production values of the first years were replaced by a color magazine as it became primarily associated with the New Theater. It contains a wealth of left cultural history and ideas. Published roughly monthly were Workers Theater from April 1931-July/Aug 1933, New Theater from Sept/Oct 1933-November 1937, New Theater and Film from April and March of 1937, (only two issues).

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/workers-theatre/v1n03-feb-1934-New-Theatre-NYPL-mfilm.pdf