A classic. Tom Barker was a self-educated, working-class Marxist, a leading figure in the New Zealand and Australian I.W.W., deported to Latin America for his anti-war and union activities, where he worked the Buenos Aires docks and became a leader of the international marine workers organizing and delegate to the Red International of Labor Unions. Below are introductory chapters published by One Big Union of his wonderfully written working-class history of sea-faring from the Phoenicians to the diesel motor.

‘The Story of the Sea’ by Tom Barker from One Big Union Monthly. Vol. 3 No. 1. January, 1921.

INTRODUCTION

It is the purpose of the Industrial Workers of the World “to build the new society within the shell of the old.” In order to do that, the workers not only have to get control of industry, but they must mater its processes as well. They must prepare themselves to be able to run industry smoothly and efficiently when the death knell sounds over capitalism and introduces the new era of industrial democracy.

To that end the I.W.W. has launched a program for the exhaustive study of the vital industries. That is the reason why the I.W.W. is the one big constructive movement in America today. As a preliminary step, it is getting up handbooks describing the different industries, giving the history of their development, their importance to society, their present status in the complicated network of modern industrial life. Their mechanical processes are entered into as deeply as the scope of a general handbook surveying the whole industry will permit. But that is only the initial step. Later will follow a detailed compilation of the technical, commercial and social phases of each industry, which will re- quire a tremendous amount of research work.

The I.W.W. has been very fortunate in prevailing upon Tom Barker to write for it a Handbook on the Marine Transport Industry. It is doubtful if there is another man in the English-speaking world as well qualified as Tom Barker to write on all the phases of that industry. Having spent his whole life on the sea, the wharves and the docks, and having made an exhaustive study of the subject, he is conversant with all phases of shipping and navigation from A to Z.

The book will appear in The One Big Union Monthly serially. Following is the first installment containing two chapters. There are eight more chapters to follow. Besides being a work of great scientific value, it is also a masterpiece of English composition, a literary treat that will be appreciated by the finest connoisseurs of the art of writing.

CHAPTER I. FROM ANCIENT TO MODERN TIMES.

Long before the days of written history, man had launched forward into the unknown seas. Under the restlessness engendered by his environment he had formed his rough coracle on the shores of Albion or pushed through the bays of warmer climes his crude raft of tree branches bound together with the supple strings from tropical climbers. These humble craft were the forerunners of the great liners and the black, squat battle cruisers of our own day. Slowly, ever so slowly, man added to his conquests and gained in confidence and in horizon through the long vista of the years.

In the palm-decked Andamans and the straits of the Eastern Seas he built and outrigged his canoe to sail with its matting-sail before the steady blow. Primitive and barbarian peoples who live near the sea or on the shores of great inland lakes all seem to have possessed some knowledge of primitive boat-building. The Indians who had settled upon the banks of the Amazon and its tributaries could have only reached their settlements through the use of the canoe. The African lakes and rivers show many and varied fashions in ancient ship-building. The Maori race–most heroic, moral and courteous of barbarians–had wandered across the Pacific Ocean in their huge war-canoes from Hawaii to Tonga and from thence to Ao-tea-roa,-their beloved “Land of the Great White Cloud”-now known as New Zealand. The race that spread itself from the Great North Land to the straits of Magellan had undoubtedly paddled its way from the Asiatic mainland through the Behring Straits. The need of food and the art of fishing, we believe, had much to do with the early contests with Mother Ocean. Man himself can trace his ancestry back to the protoplasm on the edge of the primeval sea, just in the same way as he can trace the art of boat-building from the barbarian hollowing the tree-trunk with a stone adze, to the modern yards at Clydebank, Belfast and Hog Island.

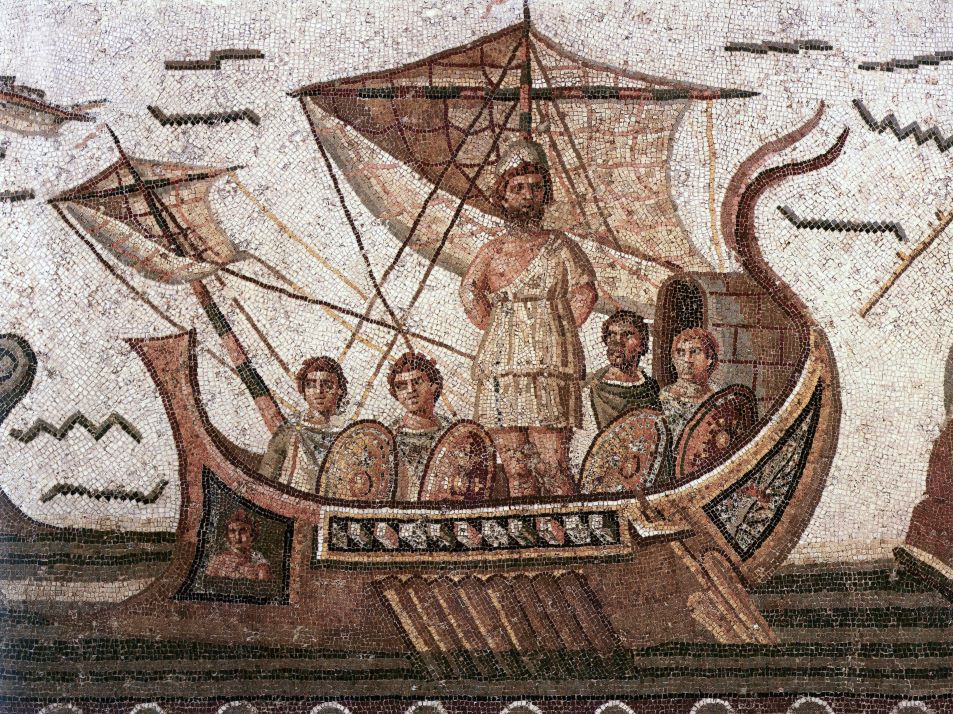

By the placid, sun-kissed waters of the Mediterranean the merchant princes of Phoenicia erected their yards. Driven by the breeze and propelled by sturdy oarsmen, their galleys visited the rising ports of Sicily, Carthage, Rome and Iberia. These keen-witted traders bartered the purple cloth of Tyre and the cedar of Lebanon for the wool of the Sicilies, the dates of Carthage and the golden apples from the Iberian valleys. They ventured through the frowning Pillars of Hercules and thrust their way through the hurtling waters of the Biscayan Sea to the shores of Albion, where they traded salt and cloth for the tin of the skin-clad Briton, who greeted them as beings from another world. Through the grey North Sea went their prows, turning sharply into the Baltic to a world of blue-eyed, yellow-haired men and women and gloomy pine forests. They wound in and out of the Norwegian fjords, touched the fringe of the Maelstrom and gazed with awe upon the Northern Lights. Those were the days when the courageous trader matched his endurance against the elements, and ventured his frail ship against the unknown seas. Today trade is in the hands of lily-handed, avaricious misers with many titles and little honor, sordid robber barons with frock-coats, front pews and unnatural carnal appetites.

Along the banks of the Yang-tse-Kiang, whose waters pour into the Yellow Sea, the Chinese had constructed their huge junks and laboriously thrashed their way to the Burmas, the Phillipines, the many isles of the Malaccan Seas, even to the shores of Madagascar and the Cape of Storms, which breaks the tremendous attack of millions upon millions of tons of crashing waters. The Chinese were fearless navigators and heroic explorers when the Britons of Albion were murdering each other in tribal wars, worshipping before the mystic mistle-toe and paying homage to their Druidical priests.

Great slave states were rising round the edge of the Mediterranean Sea. They fought out their almost endless wars in its crimsoned waters. Rome, Egypt, Greece and Carthage hurled their marine legions at each other’s throats. Chained to their huge oars, our slave forebears went down to litter the floor of the sea, and to await companions of the tempests and the wars of the years to come. The rammed Punic galley and the submarined merchant ship prow by keel both bear testimony to the saving grace of Olympus and Nazareth.

The lusty Norseman, driven by hunger from his own inhospitable shores, set out on his expeditions to ravage the plains of Normandy and Eastern Britain. His blond-haired women-folk sailed with him, fought with him, and ventured with him in his final quest of Valhalla. In the coming days of rapacious commercialism this fearless and hardy race were to play a great part in subordinating the ocean to the subduing hand of man. But their ancient brotherhood and freedom was to disappear in the process. The lousy forecastle, the “retired and condemned” navy salt-horse, and the prison cell were to be their share out of the conquest.

The galley gave way to the sailing ship both for war and commerce. Columbus’ ships crossed the Atlantic in a search for the shores of India. From this ponderous event came the naval power of Spain. The Americas opened before the avaricious eyes of Latin Europe. The galleons of Spain sailed the seas, and their golden cargoes attracted the pirates of Devonshire–now duly canonized in the Calendar of British Commercialism, and duly justified by its hand-maiden, the Church of England–to engage in their filibustering exploits. War was declared, and Philip of Spain sent his Armada, after due propitiation of the Lord God, to rout out the buccaneers and establish the legality of the right of Spain to rule the waves. God, however, was upon the side of the “meek,” and the Spanish fleet was attacked by fire near the French coast, and the remaining ships destroyed by a storm on the Irish coast. Great was the joy of the English at this victory, and the Lord God improved muchly in their opinion. The Almighty’s good graces are said to have been due to His approval of the virgin life of the good queen of England and his corresponding disapproval of the lax moral habits of Philip. This matter can well be left to a class of people whom the world honors by the name of historians, and who have ever been more concerned about a dead monarch than a living navvy.

The Spaniards spread through Mexico, Peru and Chile. The Portuguese established themselves in the Brazils. Vasco da Gama rounded the Cape of Storms, and Magellan drove his ship between the land mass of South America and the grim island of Tierra del Fuego “Land of Fire” which today is divided between the republics of Chile and Argentina, and where some of the bravest hearts in the working class movement are eating out their lives in the Siberian rigor of Ushuaia, the Saghalien of the Antarctic Seas. Tasman and van Diemen left their names to immortality by the discoveries of the huge land masses in the Southern Ocean now known as Australia and New Zealand. The lust for power, for gold, for fame, was in the heart of every explorer, every seaman, every merchant. Mother Church needed a wide earthly kingdom, and souls for Grace. The sturdy aggressiveness of the people of the sea dragged from earth’s reluctant breast her many secrets. The world was found to be round, the “four corners of the earth” of the New Testament were discovered to be non-existent and the invention of the compass made men as secure in the wilderness of waters as in their homes ashore. The blazing sun at noon and the silent stars at night were sign-posts to the mariner as clear as the Peak of Teide to the homebound windjammer.

Navigation was no longer a grope or a gamble, for charts were made and soundings taken. They were crude at first, but no cruder than the ships and no rougher than the men who sailed them. The Cinque ports of England and the Hanseatic seaside towns of Germany became entrepots. Cadiz, Genoa and Venice were the centres of vast commercial ramifications, and crowds of masts, and mariners of many tongues and varied costumes frequented the quaysides. The world was becoming smaller although ships were changing very little in their construction. The restless rovers of Western Europe with profit in their hearts and bibles in their pockets, brought the races of Africa and the East beneath their iron sway. The mild-eyed Buddhist was taught the necessity of hard work, the Chinese were educated to a taste for opium and the African inoculated with the civilizing germ of gonorrhea. The brown son of the Mexican hills was told by the missionaries to gaze into Heaven, while they stole the land from under his feet.

The groaning slaves of the Cartagean galleys were to have their counterpart in the following centuries. For the convict ships of England were to carry from her shores all those who conflicted with the savage and ruthless laws of a vindictive ruling class. The criminal from the slum and the trade union pioneer were dragged in manacles aboard these hell-ships and sent in despair to the fiendish penal settlements of Botany Bay and Port Arthur. For in those days trade unionism was a crime, and unionists were conspirators. The convict ships filled the sea with such a nightmare of desolation and sorrow as never before.

The Christian nations engaged in the revolting business of “blackbirding,” the capturing and subjugation of colored slaves. One enormity was added to another. The ruling classes of those days were almost as conscienceless and brutal as those of today, and as hypocritical–if it were possible–as the cowardly, sedentary bible bangers and platitude mongers who profess to be the followers of the slave agitator of Nazareth.

The navies of France and Great Britain carried on a long war, wrangling over the possession of great tracts of the earth’s surface and the right to exploit the native peoples and the natural resources. The war terminated at Trafalgar, where the one-eyed Nelson defeated the French and earned the right to have hideous monuments erected to his memory in all parts of Great Britain. The divorce courts missed a chance of dissecting his love affairs, which would possibly have made him even more famous.

At the beginning of the last century the pride of the merchant service was a fine fleet of clipper ships which traded to various parts of the world. The famous “East Indiamen” are still magic words in the world of ships. They were the most beautiful structures with which man ever crowned the surface of the sea. The press-gangs secured the men for the glorious navy and the shanghaier was settling down into that vile business of “supplying” men for merchant ships.

While great advances were being made ashore in different branches of industry, little of a far-reaching nature had affected the construction or the propulsion of ships. Early in the 19th century, however, experiments were undertaken to turn the great discoveries of Watt and others in the field of steam into the sphere of marine transportation. Fulton on the Hudson and Symmington on the Clyde, after many trials and many failures, were able to apply steam to aid the wind in the propelling of ships. This was an enormous advance, as it took the question of marine traction out of the hands of capricious nature, and endowed ships with both greater speed and regularity.

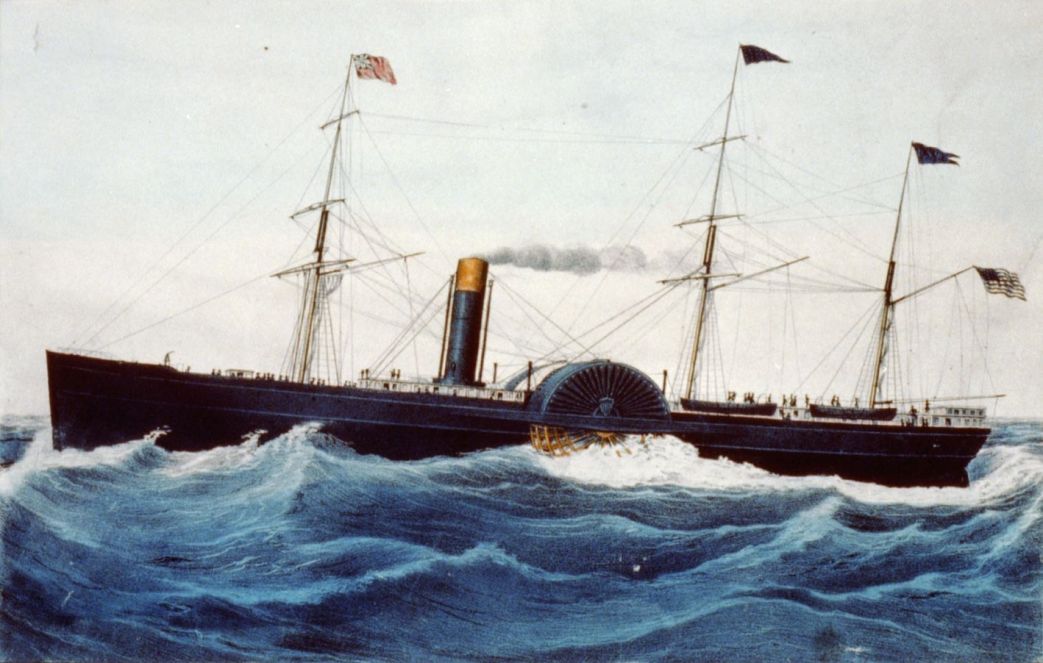

The rigging of ships underwent great changes during the ensuing fifty years. For a period steam was merely used as an auxiliary to the sails. Paddle wheels were used for a time, but they were cumbersome and clumsy, and on occasion they retarded rather than helped the ship when she was taking advantage of a good wind. The propeller was invented, which speedily scrapped the paddles. Stronger and more efficient engines were built into the newer ships. In looking over old files of illustrated papers dating back to the forties, the reader can get some idea of the wonderful advances made. In those days the structures were incongruous and weird in appearance. A shaky-looking funnel can usually be found hidden, almost, in a mass of rigging. Capitalism was driving romance from the seas. The Doldrums ceased to embarrass the homebound ships, the legend of the “Flying Dutchman” became only a storybook memory. The rousing shanties, “Bound for the Rio Grande” and “Off to Valparaiso” went out with the departure of the era of “wooden ships and iron men.”

Someone conceived the idea that ships could be built of iron. The idea was laughed at as being a challenge to the laws of nature. But it came to be, and ship-building no longer was a wood-worker’s job. Then it was that the building of ships took a great leap forward, and the Tyne, the Wear and the Clyde–great coal and iron centres–became the homes of ship-making. Little by little the elaborate rigging disappeared from steam-driven ships, until there remains today–like the holeless buttons on your coat sleeve–two lonely relics of masts, which carry the lamps and support the booms in the working of cargo.

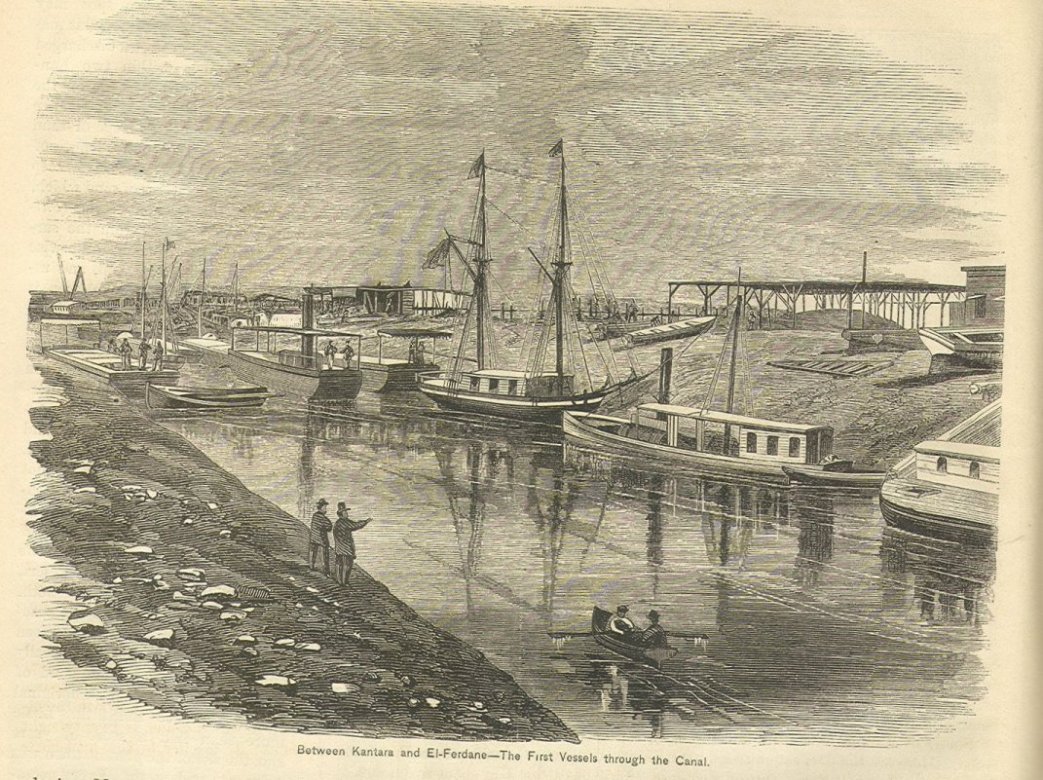

The Suez Canal opened a near way to the East, and vast ships traveled down the hottest waterway in the world, crossing that wonderful road that, we are told, was traversed by Moses, the Jewish agitator, and his fellow Israelites. Great ports, with greasy streets, strange smells and ragged workers, arose to meet the tremendous development in marine transport. The Western Ocean became a highway, and the Canaries and Fernando Noronha the post houses in a long water-road to the River Plate, where the dreaded “pampero” howls and makes old seamen whiten and wish for the open sea. Huge leviathans were there with red throbbing hearts tended by sweating men from Scotland Road and rice-fed Lascars from Calcutta; grimy, rusty, weather-beaten tramp steamers with ten nationalities aboard, with rotten food and big insurance; a rime of salt on the funnel from the heavy seas, and a Plimsoll line that cries to High Heaven.

Ships, ships, ships, everywhere! Down the Clyde and the Tyne, over at Hog Island and Nagasaki, the never-ending clanging of a million riveters. Unsightly frames swarming with human ants growing into ugly solidity! Luxurious liners with palatial staterooms for professional idlers and titled bums; tramps for the Home-Calcutta-Westcoast-Home trade; tugs for the ports; vicious torpedo craft and squat battle-cruisers. Here and there in the ports, a Norwegian full-rigged ship or a Puget Sound timber schooner: the remaining relicts of the day before Steam, Oil, Diesel and International Canals!

Capitalism forces its hand through Central America and in a few hours the New Zealand bound passenger ship or the San Francisco-Boston cargo tramp passes from the Atlantic to the Pacific, or vice versa. Panama has saved the ruling class of the sea millions of ship-miles, millions of tons of coal and oil, and millions of dollars in wages. Columbus could go that way to India now and could spare himself and the world from calling the American natives by the name of Indians.

Mother Ocean! Mother Ocean! the home as well as the grave of the pariah and the outcast, strewn with the wreckage of thy conquering wrath and the impotence of the foolery of warring, petty man! We are gathering to conquer from thy bosom the things that enchain and enslave us; to conquer the floating machines, the wonderful achievements of engineers and dockyard laborers that have made our masters rich beyond the dreams of avarice! Men from the ocean ferry, the whaler, the barque, the tug, the tramp, the dredger, the schooner, the lighter, the cable-ship, the canal boat; men from the docks, the cranes and the wharves, awake and claim your own! Awake, every man of you, from the forecastle head to the poop, from the masthead to the stokehole, regardless of your hundred nationalities and your warring creeds!

The mastery of the sea to the workers of the sea! The ships to the marine workers, and the wharves to the dockers! The Marine Transport Workers of the Industrial Workers of the World salute the Rising Dawn. With the desire for power within us, with all the fire of solidarity within our bronzed and gnarled frames we organize to master our own destiny, to retrieve our lost manhood, and to honor the great, green bosom of Mother Ocean with our Solidarity of Labor.

“Until tyrants and slaves are like shadows of night,

In the van of the morning light.”

CHAPTER II. THE EXPANSION OF THE SHIPPING INDUSTRY

The “Law of Acceleration”

The world in which we live is constantly changing. The tendency to change is steadily accelerating. I think that it is Normal Angell, the English publicist, who describes in one of his books what the terms the “Law of Acceleration.” To roughly re-state his deductions will, I believe, be a help in assisting marine workers to grasp the nature of this work. Says Mr. Angell in effect: “It took approximately 30,000 years from the time fire was discovered until the beginning of the Christian era. During that period, the race advanced more than they had in the previous hundreds of thousands of years. During the period extending from the dawn of the Christian era to the year A. D. 1800, the race advanced more than they had in previous periods combined. The law operated to an even greater extent during the years A. D. 1800 to 1900. It was very apparent that the tremendous strides made in the technical and industrial spheres entirely overwhelmed the slow progress of the three previous periods. “Then”, reasons this eminent man, “is it not logical to believe that the next twenty years (1900 to 1920) will mark greater and more outstanding triumphs and discoveries than the four earlier periods combined?”

Mr. Angell’s deductions are undoubtedly correct. The past twenty years have been remarkable in the triumph of man in the fields of science, technics and industry. We may, therefore, estimate that during the coming TEN years new inventions, new processes and far-reaching improvements will come about that will revolutionize our daily life and our relations one with the other.

Communism to Slavery

The shipping industry as I pointed out earlier in this work commenced in very early times. Progress and improvement were very slow. Over long periods they were almost imperceptible, like the forward motion of a barque in the Doldrums, with a very tiny current beneath her. The earliest crews were free savages, possibly bound on fishing and hunting expeditions. Canoes were tribal property, for while the men spent long months and sometimes years in the fashioning and hollowing of their craft they were fed by the other members of the tribe. The Maoris in their long and dangerous voyage across the Pacific to the “Land of the Long White Cloud” were tribal communists. The paddles were used by free men. The legendary places where these huge canoes landed in the North Island are sacred in Maori mythology. The Norsemen who swept the seas of northern Europe had no slaves to tend sail or man the sweeps of their sturdy galleys. It remained for the slave empires of the Mediterranean to chain their prisoner slaves to their war vessels.

Slavery arose and tribal communes of the barbarians were overthrown. Private ownership of property was in its earliest stages. The merchants of Tyre owned their ships, but their olive-skinned seamen had a vast amount of liberty. In the slave empires, even as in the empires of today, the ships of war belonged to the State, and the ships of commerce to private individuals.

Ships of Wood

During the long centuries that passed many changes took place in the structure of the ships, but practically none in the mode of propulsion. The ship that sank with St. Paul aboard on the coast of Malta, the ship that sank on the “Rock of Norman’s Woe”, the “Pinta” of Columbus, the “Great Harry”, the Chinese junk of the sixteenth century, the ships of Magellan, van Diemen and Tasman, van Tromp’s flagship with the broom at the masthead, the Arab slave-dhow, the convict ships of London, the vanquished ships at St. Vincent and the victor ships at Trafalgar were all dependent upon sails and the breeze for their speed, and they were all built of wood.

The Advent of Capitalism

When we look back over the past hundred years it is difficult to realize the wonderful changes that have taken place. Capitalism had arisen in England. It had driven the yeoman from the land to work in the factories of the towns. The British people were swindled out of their common lands by the connivance of a gang of disreputable titled thieves with the so-called democratic Houses of Parliament. As a result, the British manufacturers had goods to sell, goods which their workers could not purchase with their limited wage. So markets had to be found; and the black and yellow races had to be taught to cover decently their nakedness with the shoddy products of English child-slaves.

Thus ships were necessary for commerce and to transport soldiers and marines to stimulate, with the point of the bayonet, a desire on the part of the native for cotton duds, beads, old-fashioned fire-arms, foul spirits and other elevating and moral products of the white race. The Thames became a great ship-building district. Lordly clippers were built for the rising merchant princes. The East and West Indies opened up vast vistas of untapped wealth before the God-fearing British business man. The English Channel was crowded with the white and towering sails of heavily laden merchant men and the oaken walls of men-o’-war.

The Coming of Steam

Then steam was applied to the propelling of ships. Its effect was wonderful. If we consider what England was like 90 years ago when there were no railways, we can form some idea what difference the coming of steam made. The railway shortened the travelling time between York and London from six days to five hours. Even the earliest steam-driven ships that crossed the Atlantic made the distance in less than half the time formerly necessary when the motive power was the wind. The discovery of steam was almost entirely responsible for the tremendous alterations and changes in the industrial world.

Like all other processes, however, it was not to benefit either the men who built ships or the men who manned them. The people who were destined to reap the golden harvest from cargo and passenger carrying were persons who did not draw a plan, coil a rope or trim an ounce of coal. Tens of thousands of men lost their lives in shipwrecks in all the corners of this earth, but shipowners died in their beds, with their prospective heirs watching one another suspiciously across their well-fed bodies.

In the engine-rooms there was a steady improvement in the engines. Adaptation and study brought about more speed and made it possible for the engines to occupy less space. Ships began to depend more and more upon their engines and less upon their sails. This change affected very considerably the mining and smelting industries. Steam needed coal both for land and water traction. Countries that had little or no coal had to import it from countries that had much. Boilermaking became an art and engineering a science. Wherever coal and iron ore were found in close proximity there would spring up mighty cities of coffin-like brick houses, filled with grimy, sweating men and dismal, dirty, neglected children, who were destined to spend their lives in the endless chain of going to work to get the cash to buy the food to get the strength to go to work again.

Wood and Steam

There was always something faulty in the combination of wooden ships and steam engines. Wooden ships cannot conveniently nor safely be built too large, for timber is unsatisfactory for large ships. This has been proved only recently, when the United States shipyards constructed a large number of wooden steamers and auxiliary motor schooners, during the period of the war. They have turned out so unsatisfactorily that one can hardly visit a port from Kristiania down to Punta Arenas without seeing one or more of these “white elephants” undergoing repairs. Four were burned to the water’s edge in the River Plate in 1919, and in Buenos Aires there were two large wooden steamers and four schooners lying there for such a long time that their owners might as well have pulled down the Stars and Stripes and put up the Argentine ensign, for any use they were likely to be to anyone else except ship-breakers.

In the small wooden ship of the old days we find that the engines occupied far more space than their use warranted, leaving very little room for cargo. Therefore during the combination of engines and wooden ships, such were only used for the fast passenger services, the general run of cargo was still carried by ships which entirely depended upon the breeze.

The Test of a New Process

To be successful, every new invention or process must do one of two things. It must either produce the same amount of wealth with a smaller amount of labor or else produce a greater amount of wealth with the same amount of labor as is required by the thing it supersedes. If it does not fulfil one or both of those requirements then it will be speedily dropped. The shipping magnates, like their comrades and fellow shirkers in other industries are not in business for either relaxation, health, or for the noble cause of charity, despite all that their subsidized sky-pilots and missioners may say to the contrary. They are in the business for dividends and profits. Their interest in both the men who build ships and the men who risk their lives running ships is merely the same kind of interest that an Australian dingo displays in the sheep that he is worrying.

Therefore, when the discovery was made that ships could be built of iron and steel, the builders of ships did not delay in erecting new yards in the midst of coal and iron bearing districts. The old conservative ship-builders would have nothing to do with it, swore that it was lunacy, and croakingly predicted disaster. Naturally, they went out of business, or turned it over to their go-ahead sons. The celebrated play by Arnold Bennett, “Milestones,” is written around the change in the materials for the construction of ships. Every marine worker should see it. Hide-bound conservatism collapses when confronted with the driving forces of economic advancement. The application of iron to ship-building was one of the great changes that took the world of trade out of the conquering textile manufacturers’ hands, and put it into the mailed fist of the lords of steel, coal and shipping. Without this great change there would have been no great European war, and cotton, cocoa and soap would still have been the dominating figures in the world of today.

Competitive Capitalism.

The British Isles from then onwards until the year 1917, became the great ship-building centres of the world. Up to the beginning of the World War, Great Britain not only built by far the greatest portion of the world’s shipping but also owned the greatest portion of it. Gigantic companies arose which counted their capital by the millions of dollars and their slave helots by the tens of thousands. The enormous dividends that they made were utilized in building other ships and improving those that they had. These companies fought out competitive wars between themselves. In the cutting of passenger and cargo rates, some were squeezed out and some survived. “The big fish ate the little fish and the little fish ate mud.”

There were rate wars between British ships and German ships, Italian and American, between Liverpool and London, Hamburg and Antwerp, Sydney and Dunedin. I have been told that the Union Steam Ship Co. of New Zealand used to pay the passenger for traveling on their boats between New Zealand and Australia, in order to break down the lesser and poorer Huddart Parker Co. The laws that underlie the capitalist system are such, however, that the lessons of the wastefulness and stupidity of competition always end in consolidation. If two companies are in the one trade and supplying the same service, have the same amount of capital and the same efficiency in both production and organization, and they compete for the trade, then rupt, both must go bankrupt to leave the field to one of three things must happen: one must go bank another organization, or they must join forces. This always ends in industrial oligarchy, the absolute subjugation of the industry and the workers to a soulless domination.

Expansive Capitalism.

British capitalism fostered world-capitalism. Germany entered the arena to engage in both the construction and running of ships. Japan had overthrown her ancient system of social organization, stopped building junks and erected her yards for iron ships in Nagasaki and Kobe. The world struggle was marching apace. The patriotic and humane British shipowner, ever anxious to save his fellow countryman from Scotland Road and the West India Dock Road from the exhausting work in the stoke-hole, filled his forecastle with the Lascar and the Chinese, in order to keep down wages and thereby win the foreign trade from the encroaching German, Jap and American. The profits of the big British companies were tremendous. Their growth was phenomenal. In the same way as a gigantic avalanche springs from a tiny snowball set into motion by the frolics of the wind, so have developed and grown the shipping interests of today, until they have forced their workers beneath a callous and mechanical dictatorship and enslaved them, from the captain on the bridge down to the Chinese spud barber in the galley. Capitalism is ever thus. In a short space of time it penetrates into all the corners of earth, and when markets and raw materials can no longer be found it will totter through its own contradictions and leave the intelligent workers in control of the industries. In the midst of this march, the iron man of the days of wooden ships had worked hard and long and went down with his ship to Davy Jones’ Locker. His children, if he had any, followed in their father’s footsteps and coined wealth and gold for the cubs of their father’s boss. Jack the Sailor would, according to anemic missioners, get his reward in Heaven, and twang a harp or handle a concertina on the edge of a cloud in the sweet bye-and-bye.

The Coming of War.

When the World War came about in 1914 no one suspected that the shipping kings and the ship-builders had anything to do with it, nor that the challenge of German marine transportation had anything to do with the subsequent patriotic enthusiasm of the British shipowner. And yet when we see their balance sheets we know that they must have desired the war, for they made huge profits out of it. German shipping was driven from the seas, for that was of much greater interest to our patriotic ship-owners than the plight of the Belgians or the “sacrosanct rights of small nationalities.” The ship-owners were as much concerned about small peoples as they were about the coolie fireman or the Swedish deckhand when he was shanghaied aboard their hungry tramp steamers. Some 14,287 marine workers on British ships were killed and drowned during the war owing to submarine action. Right through the country today their dependents are starving, but that raises no sympathetic throb in the flinty hearts of the men who owned those ships, and did so well out of the disasters that befell their men. Anyway, these unfortunate men were only regarded as the riff-raff of the seas, the victims of shanghaiers, although they were the source of the luxurious houses, good food, fine silks and refined pleasures of the magnate and his lady fair. The war increased the shipowners’ grip on things tenfold. The British, American, Scandinavian and Japanese companies coined enormous profits. The Germans by losing the war also lost the greater part of their shipping. The much-vaunted action of the Brazilian government in declaring war upon the Central Powers was caused by the desire to possess, at Allied suggestion, the interned German ships in that country. The same was true of Peru and Portugal, and it was probably one of the minor reasons why the United States subsidized its press to work up a state of violent indignation with Wilhelmstrasse, after it had supplied the Germans with material and had received merchant cargoes from the merchant submarines, when they came through the Allied blockade.

The War after the War.

The Allied shipowners contrived by the assistance of their respective governments and by intrigues with neutral countries to clear German shipping from the seas. This act did not settle their own rivalries, and they set to work to over-reach each other, and cut each other’s throats as they had done in the days gone by. For although cargoes were on the increase and the carrying trade generally greater, new processes and new routes were being utilized that made it possible for the same amount of tonnage to make more trips and thereby carry more cargo than formerly. The advance in American ship-building became very marked in the year 1918, when we find American yards turning out 929 ships with a tonnage of 3,033,030, while British yards only constructed during the same year 507 ships with a tonnage of 1,628, 924. The Japanese built 198 ships of 489,924 tons in the same year. course, as I have mentioned before, some of the American ships were very faulty and quite useless for profitable cargo-carrying. They were ships for a seaman to beware of, and a source of anxiety to the insurance companies that were foolish enough to undertake the risks.

The Coming of Oil.

But as iron and steel had caused a revolution in marine transport in the middle of the 19th century, so now there were other potent forces operating that exerted great influence upon the world of shipping. The turbine engine had accelerated the speed of ships to an astounding extent. It became possible for a liner to cross the Atlantic in less than a week. Oil fuel was introduced that dismissed thousands of firemen, coal-passers and others from their form- er occupations. Less coal was required and more oil. That strengthened the position of the oil companies. It displaced miners, and coal-workers on the docks. It gave ships more cargo space, for oil-bunkers can be placed along the bilges and other parts of the ship that are of little use for cargo-carrying. In the place of the dirty, coal-blackened stoke-hole with its piles of ashes and its struggling, sweating, grimy men we see a man here and a man there, clad in clean dungarees, regulating the flow of the oil into the furnaces. When a ship arrives in a bunker port, the oil pipe-lines are laid aboard, and in a couple of hours she is ready for sea again. It must be quite evident to every intelligent marine worker that the companies that pin their faith to oil will prevail and triumph over companies that persist in sticking to coal. Science always prevails, and anything that displaces human labor is scientific, although the ignorant worker may not think so. As I have already said, a lesser amount of human labor produces a greater result and more profits for the shipowner. The intensification of profit-making gives the magnates more wealth to re-invest, until we see today that the interests of the shipping magnates in the four great carrying countries are dove-tailed and interlocked with ship construction, mining, insurance, stevedoring companies, oil, tea, real estate and innumerable other concerns. Later I will deal with the method of organization of the magnates and with the power that naturally springs from the character of their concerns.

The world may be said to be in their hands. Whatever little they have missed they design to acquire later. They own the governments with their platitudes, the gutter press with its sordid divorce and criminal details and its piffly mediocrity and inanity. The parrot-like parsons, priests and popes of Mumbo-Jumbo are their servile lackeys, and university professors and a myriad of mentally prostituted writers act as their apologists. And last, but not least, the white-spatted labor leaders with big cigars and top-hatted friends, who bawl with unparalleled effrontery, “Work harder, you stiffs, for the more you produce the more you will get!” are their henchmen.

Suez and Kiel.

The Suez Canal saved millions of ship-miles for the European shipowners. It shortened the road to India and the Far East by 40%, and strengthened the stranglehold of the British middle class upon India and the rest of the East. The possession of the alternate train route through Constantinople and Bagdad to the Persian Gulf was one of the biggest factors in precipitating the great holocaust of 1914, which in its turn was to present the world with “democracy”, “independence”, “liberty” and all the other breakfast foods invented by Woodrow Wilson and the bay-windowed bald-heads of Westminster. The Canal of Suez meant hard work for the Egyptian, and ten hours a day, a loin-cloth and a handful of rice a day for the Hindoo.

The Suez Canal increased the bank accounts of the shipping companies enormously, but never shortened the working day of the sailor by a second nor improved the ration scale by an ounce of green salt pork. But there are prominent labor leaders who will tell the world that all this was done in the interests of the workers, for which they will probably receive a degree from some university owned and controlled by the master class.

The Kiel Canal was another triumph of the shipowners. Of course, like Suez, it was also a strategic necessity from the naval standpoint. During the war period it enabled German warships to pass from the Baltic to the North Sea in a few hours. It is now saving the use of thousands of tons of shipping every year and cuts two days off every voyage made from Western Europe to the Baltic. It will save the shipping magnates thousands of hours of labor time as well as thousands of tons of coal and oil. It will increase the number of ship trips and give the owners more profit, but the marine workers will have more unemployment as a result. Competition for jobs will be keener in Malm, Reval and Hull, and the companies will make much out of their natural advantages over their slaves.

Panama.

The recent opening of the Panama Canal was another great event in the shipping world, and also had its effects upon the men who man ships. It shortened the sea distance between San Francisco and New York by more than one half. Instead of the long trip around the South American continent, it is now possible to travel through the locks in Central America. This gigantic enterprise, cost millions of dollars and thousands of lives, working class lives. It also shortened the distance between Europe and Chile, Australia and New Zealand, and thus abolished the risks incurred by sailing in the low latitudes of Cape Horn. It effected a great difference in the sea distance between the North Pacific coast ports and those of the River Plate, and between the Atlantic coast ports, and of the nitrate towns of Chile. It strengthened enormously the position of the United States, both economically and politically. It transferred the carrying of cargo from the American railroads to the ships, for it is now cheaper to send a ton of cargo from Seattle to Philadelphia, via Panama, than to send it by a freight train. It strengthened the Octopus of Shipping, the Autocracy of Merchant Navies.

The Octopus and Its Victims.

When we study a world chart, with its converging ocean routes, we can form some idea of this huge world autocracy. Three great octopuses spread themselves out from the United States, Great Britain and Japan. Their tendrils cross and recross each other like the threads in a huge patternless spider’s web. The whole world is in their tentacles. Under their direct ship-board rule are 900,000 ship-workers of every nationality under the sun. There are in the vicinity of 1,100,000 dockers, longshoremen and allied workers scattered in every nook of the world wherever these tentacles penetrate. Strong and silent are these industrial giants, the “high pontiffs, priests and kings” of ocean transport.

The opening of Panama has augmented this grip, just as Kiel and Suez did in the past. It certainly gives American shipping the advantage, for the moment at least, but we must not forget that the competitors in this march for industrial conquest are inextricably connected with the shipping concerns of other countries. And in every port in the wide world the effect of the new route is reflected by the hungry hordes of our fellow workers who are walking round the docks, begging the chief stewards, officers and engineers for jobs, which in the old days were always waiting for them. New routes, oil fuel, canals, all these have had the effect of strengthening the ship-owners and weakening the toilers of the sea. It is the business of this handbook of the Marine Transport Industry, in a crude fashion, to waken the workers of the stokehole, the galley and the bridge to an understanding of the economic forces that affect them, and to forge methods of counter-organization. To that end we hope that this book will be passed around and that these matters will be discussed by the boys in their watch below.

The Deisel Motor.

Some years ago a small German with a large head made a great discovery, which is destined to shake the world of industry to its very bottom. I refer to the Deisel Motor, which is named after its inventor. When this invention was mooted in engineering and ship-building circles all kinds of efforts were made, some of them very unscrupulous, but quite in keeping with capitalist and ship-owning morality, to secure the plans. This invention was not only calculated to revolutionize the propulsion of ships, but land transport also. It could be used to haul trains both on rail and on the open road. It could be applied to farm tractors, and, in fact, to any and every form of wheeled transport. It could be manufactured very cheaply, was very simple in construction, and would burn any kind of crude oil. In fact, upon a fully outfitted motor, the by-products which could be derived from the burning of the oil would more than repay the original cost of the oil. Therefore the motor could be run at a profit.

The oil runs directly to the motor, where a forced draught explodes it. This explosion is the motive power that will transform industrial processes everywhere. No boilers are necessary and the engine-rooms of ships that use the new motor are very compact and small. It gives them much more cargo space than a similar-sized ship which also burns oil, but possesses the ordinary steam-making boilers. The contrast between the Deisel-engined ship and the coal-burning ship is much greater. A motorship usually has a very small smokestack, and the smuts, dirt and grime that are the second mate’s and the bosun’s despair are missing from this new type of ship.

This type of ship has not yet made a general appearance in the British and American merchant service. The rights for the invention for marine purposes were placed in Danish hands by Doctor Deisel. Just before the war, we are sorry to say, this great industrial genius was found to have disappeared from a ship while crossing the North Sea. Whether he committed suicide or was murdered by the agents of the disappointed engineering and ship-building companies will never be known. The big yards in Copenhagen commenced to turn out a large number of these modern ships, particularly for the Eastern Asiatic Company. The ship “Siam” inaugurated the service of this type of motorship to Australia in the latter part of 1915. Large numbers of these ships are now sailing out of the Scandinavian countries. The Johnson Line of Stockholm possesses 27 large cargo carriers, speedy, clean and beautiful, engaged for the most part in the South American trade. Both the Norwegians and the Danes have a steadily increasing number of them. Early in 1919, the Swedish motorship “Bullaren”, fitted with Deisel Bullinger engines, arrived in Buenos Aires from Gothenburg. The trip took her less than 20 days. She had electric winches, which worked the cargo noiselessly and speedily.

What of the Future?

The Deisel motor is now being utilized in the engine-rooms of new British warships. The era is speedily coming when steam is no longer going to serve as the motive power for ships. They will be electrified through the new process. However, the increased earning capacity of Scandinavian ships has not increased proportionally the wages of the men who work aboard. More cargo is carried in a shorter time and with fewer men. All that these advances mean to our fellow-workers is more unemployment and starvation.

This process is not likely to stop. On the contrary, discoveries will pile on top of each other, and in a corresponding degree so will also the misfortunes of the toilers of the sea. Many of the great inventions of the war period are going to be transformed into peace-time uses. Many of the discoveries made for purposes of destruction on land will be altered to suit the needs of marine transport. They will, like steam, iron ships, oil, canals and motors, strengthen the grip of our masters, take the industry entirely out of the rut of haphazard, cut-throat competition, and bring us men of the sea and the docks beneath the ruthless heel of an iron despotism. That power is in the making. Every day we see the national governments whatever their label acting under the instructions of their masters, enforcing restrictive legislation and driving the workers each day into a more precarious position. Each day the gulf between the shipowner and his slave grows wider. From day to day the feeling of antagonism intensifies until the world is becoming but an armed camp of classes, those who obey and create and those who command and possess.

To grasp the dictatorship over the sea is the mighty task of the Marine Transport Workers of the Industrial Workers of the World.

One Big Union Monthly was a magazine published in Chicago by the General Executive Board of the Industrial Workers of the World from 1919 until 1938, with a break from February, 1921 until September, 1926 when Industrial Pioneer was produced. OBU was a large format, magazine publication with heavy use of images, cartoons and photos. OBU carried news, analysis, poetry, and art as well as I.W.W. local and national reports.

PDF of full issue: https://archive.org/download/one-big-union-monthly_1921-01_3_1/one-big-union-monthly_1921-01_3_1.pdf