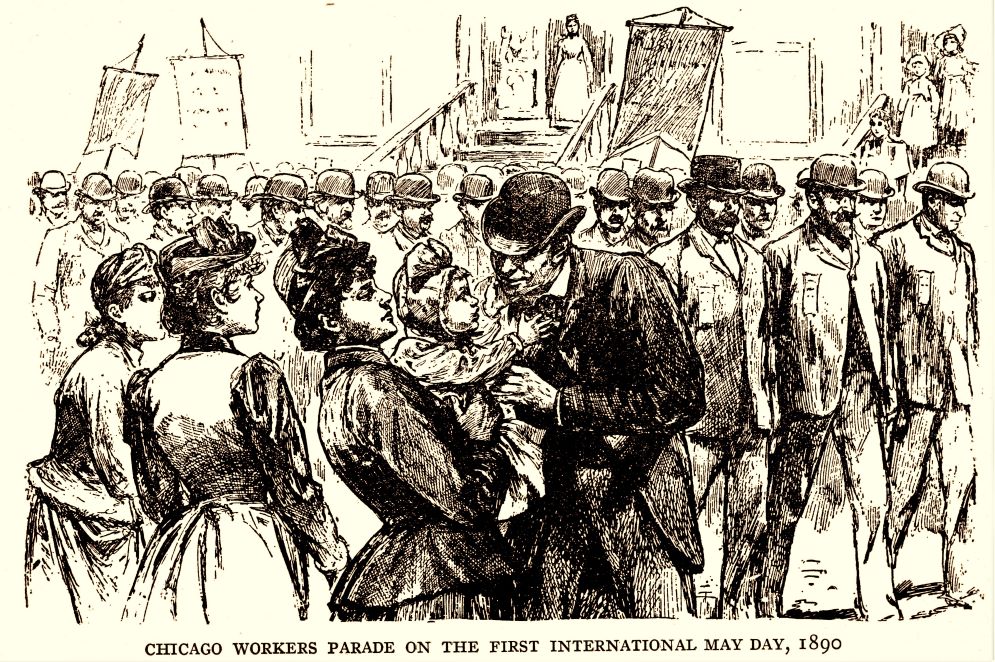

The very first workers’ May Day is held in New York as 20,000 march in the driving rain. May Day began in response to the Socialist International’s 1889 call for a day of protest for the eight hour day to be held on the anniversary of the 1886 eight-hour strike which led to the ‘Haymarket Affair’ and martyrdom of comrades Albert Parson, Louis Lingg, Adolf Fischer, George Engel, and August Spies on November 11, 1887.

‘May Day in New York Under the Banner of Socialism’ from The Workmen’s Advocate (S.L.P.). Vol. 6 No. 19. May 10, 1890.

Twenty Thousand Turn out in a Pelting Rain, They Demand Eight Hours as a Measure of Temporary Relief, but they Repudiate the Wage System and Urge Independent Political Action on the Socialist Platform.

If the capitalists who own the earth had the power to make the weather they could not have prearranged a meaner storm than that through which seventy labor organizations of New York city, numbering together twenty thou sand men, marched to Union Square on the 1st of May. They came from all parts of the town, with red flags and banners, singing the Marseillaise. The demonstration was imposing even under the pelting rain. What it might have been if the evening of the day had kept the promise of its morning, when the Sun rose in all his glory, may be inferred from the fact that the Jewish trades, who had decided to have an afternoon procession of their own on the East side, were 10,000 strong when at 4 p.m. they started from their headquarters. Shortly after, the storm broke out in all its fury, and although the processionists stood it manfully until 6 o’clock, many of them were prevented by the soaking they had received from again turning out in the evening; so that hardly 5,000 of them were in line when their bands and banners heralded their presence at Union Square. Again, there were very few ladies in the vast crowd, although large numbers of them would have attended if the weather had not proved so forbidding.

For over an hour successive organizations continued to pour into the square from various directions, and although the stream of humanity that flowed out was as large as that which flowed in, so long as the meeting lasted the whole plaza was crowded. At 8 p.m. no man, however powerful, could have cut his way through the large masses of people in front of the ladies’ cottage and around the two trucks from which speakers were doing their best to be heard above the martial strains of the Marseillaise. The New York Socialist Sections, together with the Unions that meet at the Labor Lyceum, did not reach the square until 8.30. They made a fine display and were enthusiastically greeted.

At 9.45, when the meeting was about to adjourn, other lands were heard and another great procession was seen marching steadily through rain and mire with red flags and torches. They were the plucky men of Brooklyn, headed by the Socialist Sections of Kings Co., and Newtown. They were greeted with a mighty hurrah, to which they responded in thundering style. These were the Brooklyn organizations represented in that procession:

BROOKLYN CONTINGENT.

Furniture Workers Union No. 8.

German Framers.

Section Kings Co. S.L.P.

Carpenters Union No. 291.

Painters Union No. 8.

Section Greenpoint S.L.P.

Section Newtown S.L.P.

American Section S.L.P., Brooklyn.

Bakers’ Unions No. 34.

Ladies’ Shoemakers Union.

Tellers Union.

Cigarmakers Union No. 149.

Clothing Cutters Union “Progress.”

Bricklayers Union No. 9

Locksmiths’ and Rallingmakers’ Union.

Cement Laborers Union.

Arbeiter Mannerchor.

August Delabar, Sec’y of the International Bakers’ Union and of the New York American Section S.L.P., presided at the ladies’ cottage. The first speaker was Thaddeus B. Wakeman. He said in substance:

“When the sun rose this morning he saw labor from the Ural Mountain to our own Pacific united in one great demand, one assertion to one great right–the right to live. He saw labor united not only in a request but in a demand. Labor will no longer live in slavery. It claims the equity that those who produce most shall no longer enjoy least. My friends, the ultimate results of this demand are certain, but immediate requirements must not be neglected. Civilization cannot rise higher than its source, and the source of civilization is labor. Eight hours is a good beginning, but the only way that the disgrace of the present civilization can be done away with is by a reorganization of society. If this is nationalism and socialism, you are welcome to it, and make the best of it.”

George McVey, Secretary of the United Pianomakers, then read the following resolutions, and had frequently to stop while the crowd cheered like thunder.

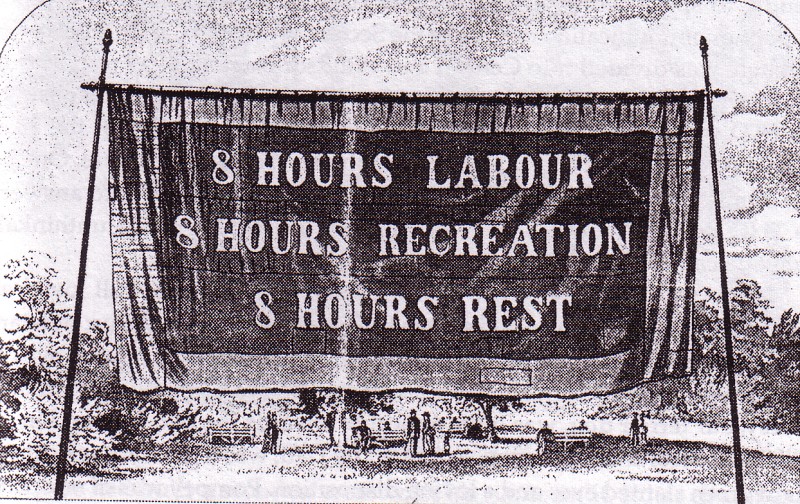

Whereas by a convention of the American Federation of Labor this day has been designated for the inauguration of a new and final eight-hour movement not to be relaxed until its complete triumph is achieved;

Whereas the International Labor Congress, held at Paris in July, 1889, reenforced said resolution by a call issued to the workingmen of the world to assemble on this day and manifest unanimously and simultaneously that eight hours should constitute a day’s work. and that labor will unite its efforts to secure the enforcement of that demand for all who labor the world over.

Whereas the working men throughout the civilized world are this day holding demonstrations to carry out the spirit of these resolutions;

Whereas the active battle for the establishment of the eight-hour day has been inaugurated in this country by the Carpenters and is to be continued trade by trade until it has been secured by all;

Whereas, owing to the workings of capitalism the eight-hour demand can be but a measure of temporary relief for the exploited masses and nothing short of the abolition of the wage-system and the reorganization of society on a socialist basis can effectively solve the labor problem; therefore be it

Resolved: That we, the working masses of New York, under the auspices of the S.L.P., on Union Square assembled, uniting our voices with the proletarians of all countries, reassert the demand of the aforesaid conventions, that the reduction of the hours of labor to eight is of immediate necessity and that we pledge our sympathy and support for all efforts of labor to secure that end;

Resolved: That in order to make its establishment permanent and applicable to all labor, the eight-hour day should. be decreed by statute and the economic struggle should be re enforced by political action to secure such legislation;

Resolved: That while struggling for the eight-hour day we will not lose sight of the ultimate aim of the proletarian movement, the abolition of wage slavery, and urge all wage-workers to rally under the banner of the Socialist Labor Party to bring about that final change.

Prof. De Leon spoke next. So great, he said, had been the progress of economic knowledge among the wage-workers, that the fallacies which may still be taught in our colleges at the command of our plutocracy are only casting a deserved ridicule and odium on those professional men who show themselves ignorant enough or subservient enough to teach them. In the light of history, and of all the facts scientifically grouped and coordinated, the wage-class has possessed itself of the true science of industrial government and is surely marching to a new social order. As a preliminary step, necessary to further organization, a demand is now made for a shorter workday. This must and shall be gained. But the battle will continue until the laborer gets the full product of his labor.

S.E. Shevitch’s turn came next. He was enthusiastically greeted. Taking for his text the inscription on a transparency which read “This is the Beginning of the end.” he said: “This is, indeed, the beginning of the end. The end of what? The end of political corruption and of prostitution and of thieves in public office. It is the end of such things as the Mayor of our great metropolis being shown up as a corruptionist, without even the courage to answer the charges against him. It is the end of corruption in all officials from the Sheriff up to the highest Judge of the Supreme Court. It is the end of the social conditions where one million unemployed exist while a handful of millionaires own half the whole produce of the land. (Pointing to a red flag behind him): Be true to this flag, which is dyed scarlet not in the blood of our enemies but in the blood of our martyrs.”

P.J. McGuire, vice-president of the American Federation of Labor, arrived just in time to make the last speech. He was just from Philadelphia, and brimful of good news. Out of 160 towns where labor had gone in for eight hours Victory, he said, had already been won in seventy. He hoped that they would all stand by the carpenters and joiners when they started the movement for eight hours on Monday. Then success would be assured. He aroused tremendous applause by stating that in Chicago the victory was practically won, and that in Milwaukee and Duluth the movement had been crowned with success. Two German speeches were delivered from a large truck in Seventeenth street, near Fourth avenue. August Waldinger was Chairman, and called his end of the meeting to order at twenty-five minutes past eight o’clock. The German Section of the Socialist Labor Party, Cloakmakers’ Union, Brass Workers’ Union, Clothing Cutters’ Union, Cigarmakers Union, Progressive Tailors’ Union and Barbers’ Union made up the audience about the truck.

Henry Emrich was the first German speaker. He said: “You have not come here to listen to dry theories on the eight-hour movement, but hear that thousands of workers all over the world are determined to have their rights. The movement is growing. It is impossible to club it down, to hide it behind prison walls or to down it with cannon and shotguns. The idea has taken hold of the masses. It is international, and it will be successful even if it should rain something besides water, as may be done in Europe today. Our demand has set the whole world on fire. Someday the regiments of Labor will become army corps and then the solution of the movement will be reached. It could not be solved on the green table of diplomacy in Berlin. It is the duty of workingmen to see that our present civilization does not go to ruin. Everywhere corruption reigns. Work for agitation, education and organization, and learn discipline.”

Paul Grottkau spoke next in German. He said: “Everywhere the workingmen are standing up and demanding their rights. The thrones of the rich and powerful are trembling. It is our duty to be active, to be steadfast, to organize, and to use all our endeavors in aiding this great movement. Today the workingmen gather around the red flag; this red color means better conditions and a higher civilization. The thrones of Europe are falling. Eight hours is now the question. What will the next question be? What will the last question be? He that has ears to hear, let him hear. It is only by self help that workingmen can secure what they want, and on themselves alone they must rely to obtain it.”

Daniel Harris, of the Cigarmakers, spoke in English and dwelt ably upon the necessity of reducing the hours of labor and the benefits that would flow from the general enforcement of the eight-hour workday.

Walter Vrooman made a brief speech in English in which he said that this was the grandest and happiest day in the history of labor. For the first time workingmen throughout the world had on this day, by mutual accord, met under the same banner for the same cause. It marked a new era, there of universal brotherhood, peace, justice and true civilization.

The truck near Broadway was surrounded by the Hebrew trades. Aaron Henry presided. H. Zametkin said that many Jews of Russia, Germany, Austria and many other European countries had been driven out of the Old World by persecution. But by coming to America they had merely exchanged military despotism for capitalistic tyranny. Now, however, they were organized and would no longer be a despised class.

A. Cahan spoke in the same strain and remarked, amid great applause, that for the first time in the history of the labor movement in this country twelve thousand Hebrew workers had marched under the banner of organized labor.

The Workmen’s Advocate replaced the Bulletin of the Social Labor Movement and the English-language paper of the Socialist Labor Party originally published by the New Haven Trades Council, it became the official organ of SLP in November 1886 until absorbed into The People in 1891. The Bulletin of the Social Labor Movement, published in Detroit and New York City between 1879 and 1883, was one of several early attempts of the Socialist Labor Party to establish a regular English-language press by the largely German-speaking organization. Founded in the tumultuous year of 1877, the SLP emerged from the Workingmen’s Party of the United States, itself a product of a merger between trade union oriented Marxists and electorally oriented Lassalleans. Philip Van Patten, an English-speaking, US-born member was chosen the Corresponding Secretary as way to appeal outside of the world of German Socialism. The early 1880s saw a new wave of political German refugees, this time from Bismark’s Anti-Socialist Laws. The 1880s also saw the anarchist split from the SLP of Albert Parsons and those that would form the Revolutionary Socialist Labor Party, and be martyred in the Haymarket Affair. It was in this period of decline, with only around 2000 members as a high estimate, that the party’s English-language organ, Bulletin of the Social Labor Movement, appeared monthly from Detroit. After it collapsed in 1883, it was not until 1886 that the SLP had another English press, the Workingmen’s Advocate. It wasn’t until the establishment of The People in 1891 that the SLP, nearly 15 years after its founding, would have a stable, regular English-language paper.

PDF of full issue: https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn90065027/1890-05-10/ed-1/seq-1/