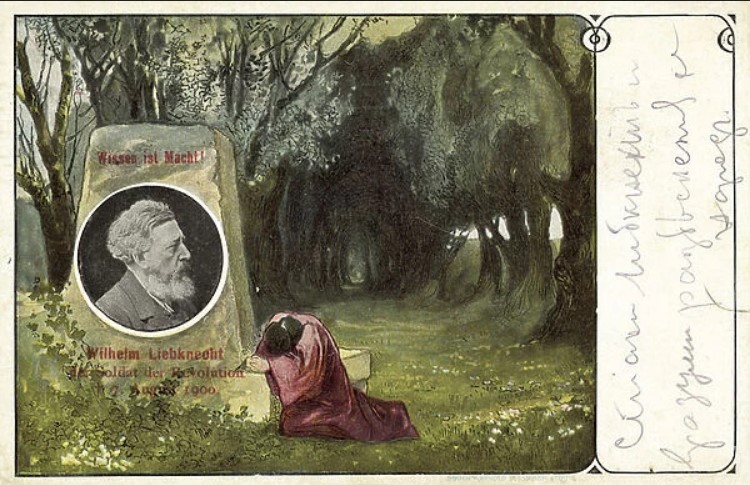

A picture of the mass funeral for Wilhelm Liebknhect from delegate of the British Social Democratic Federation, Herbert Burrowes.

‘Wilhelm Liebknecht’s Funeral’ by Herbert Burrowes from the Social Democratic Herald. Vol. 3 No. 12. September 12, 1900.

Never Did Kaiser or King Hold Such Reception at their Death–No Such Scene Ever Before Witnessed in Europe

The saddest, but at the same time the most glorious and inspiring function I have ever witnessed, is over, and our comrade, Wilhelm Liebknecht is at rest in his honored grave.

Delegated by the Executive Committee of the S.D.F. to attend the funeral, I left London on Friday night accompanied by our comrade, Saunders Jacobs, who had also been appointed to attend by our Stratford branch, Mrs. Jacobs, and their little boy, who was to receive his baptism of continental Socialism. With heavy hearts we arrived at Berlin. To me the sense of personal loss grew keener as we neared Charlottenburg, and it was with a sinking heart that I climbed the stairs to the well-known and modest fourth-floor flat in the Kantstrasse. Many times before had Liebknecht cheerily accompanied me, and now the home he loved so well was desolate. I took with me the wreath, which I had brought from the executive, of red and white flowers, with Liebknecht’s initials in red geraniums in the center.

The dead man’s small study, with its piles of papers, where so many well-known men and women had sat and talked with him, was strangely still and silent, and the air was laden with the almost overpowering scent of the innumerable wreaths and flowers which had ready been sent from all parts of Europe. By the actual time of the funeral five thousand of these had arrived, and the Berlin post office states that never for kaiser or for king had such a wealth of flowers passed through their hands. Of Mrs. Liebknecht and the family it is, of course, impossible for me more than briefly to speak. In tears they clasped hands and welcomed me as the bearer of affection and sympathy from the England which husband and father had loved So well.

Afterwards I went on to the Vorwaerts office to learn the actual arrangements for the next day. Here, as always, the calm strength of the German Socialist party forcibly struck me. Intense grief, but no hurry, no flurry, everything down to the last detail thoroughly arranged, and work proceeding as quietly and regularly as usual. I learned that from nearly all the countries in Europe representatives had arrived, and that for the morrow an enormous gathering was expected.

And so it proved. Let me say once for all that the whole funeral is indescribable. No written or spoken words can convey any sense whatever of its simplicity, its grandeur, and its strength, for that latter word is the best I can use. From seven o’clock this morning tens of thousands of people from all parts of Germany poured into Berlin, and when we reached Charlottenburg we found a living sea of humanity. Once more we ascended to Liebknecht’s rooms to take a last farewell. In his sitting room we found him reposing on the lid of the coffin, covered with wreaths. At his feet the inscription in bronze which was presented to him by his fellow Reichstag members on his seventieth birthday. The body had been partially embalmed, and the face was covered. It would have been sacrilege to have disturbed that covering, and personally I felt that I would rather remember him as I knew him living, with cheery face and laughing eye. A moment we stood, and then we joined at a rendezvous the leaders of the party. the Vorwaerts staff, and the foreign delegates. Then, led by Paul Singer, we wended our way to the house and waited for the sad commencement. Presently bared heads noted that Liebknecht had begun his last journey. Never can I forget that journey. We had to march ten miles from the west to the east of Berlin. In long procession 100,000 men and women guarded the body, and in the streets it is no exaggeration to say that a million more must have been present. For the whole of the ten miles, on both sides of the streets, they stood always ten deep, and in many instances twenty. As we passed the side streets we saw that as far as the eye could reach they were also full. Every window, and every one of the balconies for which Berlin is famous, had its own crowd.

Even the police, who for once with admirable discretion had almost effaced themselves, leaving to the people the management for one day of their own business, acknowledged that never had kaiser or king held such a royal reception in their death. No such scene had ever taken place in Europe. Our French comrades said that the nearest approach to it was the funeral of Victor Hugo.

The hearse was followed by the Socialist members of the Reichstag, headed by Bebel and Singer, whose faces were white and drawn with pain. Then came the Socialist municipal councillors, the foreign delegates, the Vorwaerts’ staff and representatives from the cities of Germany. It shows the bitter feeling of the bourgeoisie when I mention that not a single member of any of the other political parties in the Reichstag openly attended the funeral. But the dead man did without them, as he had done while living. We were told that there were six bands in the procession but we heard not a drum nor a funeral note. The concourse was too enormous. Nothing for hours but the steady ceaseless tramp of conscious Socialism, and it was the music of that which, could Liebknecht have heard it, he would have valued above all else.

As the evening shadows began to lengthen we learned that ahead of us was another procession of Liebknecht’s constituents. A mile from the cemetery gates we found that, with their wives and children, thousands of them (he gained over 60,000 votes at his last election) had lined each side of the road and were waiting for us with bared heads. And so the body of their loved leader, member, and friend passed through a human aqueduct, the living walls of which were his personal friends. We turned at last into the peaceful dwelling of the dead. The cemetery is a communal one belonging to the city of Berlin, and it was chosen because in it the police had no power to prevent speaking.

Into the little hall, which would only hold about 200 of us, the coffin, a wooden one encased in a massive copper sarcophagus, was reverently carried and placed in an alcove which was embroidered in ivy and laurel and lit by scores of massive wax candles. By this time the growing strain had become intense, and it culminated when from an ante-room we heard the notes of a weird funeral dirge exquisitely sung by an invisible workmen’s Socialist choir. The undercurrent of sobs from men and women was almost a relief, for the strain was growing too great to be borne. Gently Singer beckoned the foreign delegates to take their places by him, and then Bebel stepped to the side of the coffin. and delivered the funeral oration over the body of him who for thirty-five years had been his closest intimate and friend. Broken by emotion, his words told of the dead man’s character and work and of what in him we had lost. Then in quick and brief succession Adler, his spare form quivering with emotion; Lafargue, with passionate declamation for revolutionary Socialism; Gerault-Richard; myself, with our message of sympathy from England: Anseele, with his fervid Belgic eloquence, and comrades from Holland, Denmark, Switzerland, Hungary, Poland all voiced, not merely lamentations, but hope for the Socialism of tomorrow. Then another dirge, and slowly we took our way to the grave. In the rays of the setting sun the procession twined in and out of the winding paths, and through the green trees the sheen of the coffin and the red of the wreath ribbons gleamed, curiously enough, like a rosy dawn, typical of what the Socialism for which Liebknecht had lived and died should yet be. The closing and impressive oration at the grave was delivered by Singer. Two more songs by the choir, with a growing note of triumph in them, the countless wreaths, their ribbons detached to be given to Madame Liebknecht, were piled in picturesque confusion, and at last Liebknecht, the old soldier of the revolution, was at rest, as he would have wished, under the benedictions of his comrades and friends. For hours the vast crowd filed silently past with bared heads to take the last look at their leader, comrade, and friend.

The Social Democratic Herald began as the Social Democrat. The Social Democrat was the paper of Eugene Debs’ pioneering industrial union, the American Railway Union. Begun in 1894 as the Railway Times, in July of 1897 it was renamed The Social Democrat and served as the paper of the Chicago based Social Democratic Party. First published in Terre Haute and then Chicago, the paper was produced weekly. After a split with Utopians who retained the paper, Debs’ published The Social Democratic Herald. When they joined with the Springfield, Massachusetts based Social Democratic Party in 1901, the Socialist Party was born. Victor Berger took over the paper in 1901 and moved it Milwaukee where it ran until 1913.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/social-democratic-herald-us/000908-socdemherald-v03n12w114.pdf