‘White Labor Policy in South Africa’ by George Padmore from The Crisis. Vol. 45 No. 6. June, 1938.

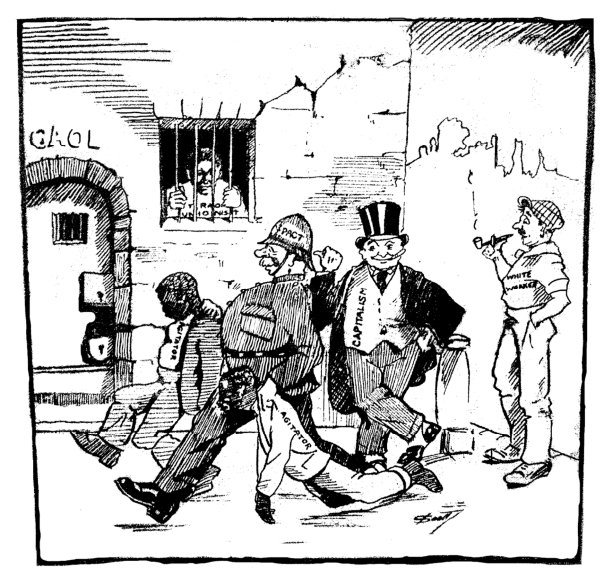

Black labor in South Africa is really enslaved and white labor has joined with the state and the capitalists in holding the blacks down with rigid laws which take not only their civil liberties, but their right to work in any except certain occupations.

Lenin spoke of the “bourgeoisification” of the upper strata of the white workers as a heavy weapon in the hands of imperialists against the Social Revolution. He pointed out that the process of identifying the interests of this labor aristocracy with those of the ruling class is an element arising out of the development of capitalism during its imperialistic stage. And nowhere is this phenomenon more apparent than in South Africa, where white labor has completely divorced its interests from those of the natives, to the detriment of the latter, upon whose exploitation it fattens.

For “the European worker is haunted by fear of competition with the great masses of native laborers,” is the declaration of a South African trade union memorandum. “Self-preservation is the first law of nature, and so the policy hitherto adopted has been one of ‘keeping the native in his place,’ in order that certain of the higher-paid jobs might be retained as the special preserve of the European worker.” This policy, which has the endorsement of the Labor Party of the Union, is implemented by legislation, and has accentuated the division between white and black labor.

“The industrial policy of the labor movement is the ‘civilized’ labor policy, which means in practice the substitution of European workers for native and colored workers wherever and whenever possible,” resolved the South African Trades Union Congress in 1925.

Thus, at the instigation of white labor, the Government passed the Color Bar Act in 1926. This law legalizes racial discrimination in industry by making it a criminal offense for natives to be employed in skilled occupations. It works out, therefore, that every white occupies a supervisory position over the blacks. Moreover, the whites are guaranteed a minimum wage towering above that of the blacks. In the gold mines, for example, the white worker gets £1 (about $5) a day minimum, as against the average of £2.10 (about $12.50) paid to the black worker for a month of thirty working days!

Parasitic Class

The European workers in South Africa constitute the most parasitic section of the international working class. Thanks to the Color Bar, they live in a style granted only to the higher placed workers and professionals in Britain and America. Obviously they are interested in aligning themselves with the capitalists in exploiting the blacks, and the division arbitrarily created is aggravated by the fact that the white workers form part of an alien racial minority which is determined to maintain its domination over the native majority. This chauvinist attitude was formulated by Sir Thomas Watts in a letter to The Times some years ago: “The white man, English as well as Dutch, is determined to do all he can to remain, and what is more, to rule. He hopes to get the sympathy and support of the Mother Country. If this is withheld he will not be deterred. To those who say England cannot be a party to a great act of injustice, I would reply that this matter is to us in South Africa such a vital and fundamental matter that no ethical consideration, such as the rights of man, will be allowed to stand in the way.”

To maintain this domination over the natives, no black worker is permitted to enter a white trade union. The European trade union movement in South Africa is represented by the Trades’ and Labor Council, composed of the Trade Union Congress and Cape Federation of Labor Unions and their affiliated craft unions and associations. They number about a hundred, and cover the engineering, metal, mining, building, printing, clothing and food industries.

Not only does the movement refuse entry to the blacks, but it declines unity with native organizations. The Industrial and Commercial Union, founded in 1919 by a young Nyasaland native, Clemens Kadalie, was the first effort at organizing a black labor union. Although conceived as a purely trade union organization, the very character of South African conditions forced the I.C.U. to assume leadership of the political as well as the purely economic struggles of the Negroes. Despite official persecution and hostility from organized white labor, it gained enormous strength economically and became a formidable political power in the hands of the blacks.

In 1928 the I.C.U. addressed an appeal to the Trade Union Coordinating Committee—the organization combining the Trade Union Congress and the Cape Federation of Labor Unions— to be included with the white workers in a unified labor movement. In reply the committee issued a memorandum acknowledging “that sooner or later the national trade union movement must include all genuine labor and industrial organizations, irrespective of craft, color or creed. The question is how and when,” and the document went on to suggest, “a considerable amount of propaganda was needed among the union membership before affiliation can take place with benefit to all concerned.” It was generally feared that the membership of the black union would outvote the European organizations and force them to abandon their discriminatory practices.

Alliance with Capitalists

This fear of losing their privileged status is the bogey which haunts the white workers and drives them into alliance with the capitalists against the natives. This unity of race as against class accounts for the widespread racial chauvinism which permeates all strata of the European population, and makes the Union the world’s classic fascist state. For here a racial minority of 1,800,000 mercilessly suppresses 6% million blacks in their own land, denying them the most elementary democratic and human rights.

The natives are hedged in on all sides by a system of pass laws which limit their liberty of movement and reduce them to serfdom. Rigid laws deny them freedom of speech, press and assembly, and forbid their appearance on the street after nine o’clock at night. Because they have no right of representation, their ills cannot be redressed through parliamentary channels.

Taxed out of all endurance, bearing the economic burdens of the Union and debarred from the fruits, there is only one way out for the native. He must rely upon himself and seek ways and means of organizing his forces and exploit every conflict within the camp of the ruling class to press forward to his goal of self-determination. In this drive for unity the natives must draw in the Indian and colored workers of South Africa, who are also victims of racial discrimination. This does not mean that they should not welcome whatever assistance and support individual politically advanced white workers or groups might extend to them from time to time, but it would be a delusion for the blacks to place any faith in the South African Labor Party or the trade union bureaucracy, which are becoming more and more identified with the state. Even the unemployed and poor whites who might be expected to draw closer to the black and colored workers, are being organized against the natives by the fascists, who are represented by a number of associations, among them the New Guards, the Grey Shirts, the National Socialist Democratic Movement, and Dr. Malan’s party, which is at present carrying on a campaign for the exclusion of Jews from South Africa and the banishment of all natives from the towns.

The future of South Africa is tied up with the future of Europe and the British Empire, and because of this, the native workers must close their ranks and prepare themselves, so that when the opportunity arrives they will be able to strike a decisive blow against the brutal system of Afrikander Imperialism which has reduced them to a condition hardly better than chattel slavery.

The Crisis A Record of the Darker Races was founded by W. E. B. Du Bois in 1910 as the magazine of the newly formed National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. By the end of the decade circulation had reached 100,000. The Crisis’s hosted writers such as William Stanley Braithwaite, Charles Chesnutt, Countee Cullen, Alice Dunbar-Nelson, Angelina W. Grimke, Langston Hughes, Georgia Douglas Johnson, James Weldon Johnson, Alain Locke, Arthur Schomburg, Jean Toomer, and Walter White.

PDF of full issue: https://archive.org/download/sim_crisis_1938-06_45_6/sim_crisis_1938-06_45_6.pdf