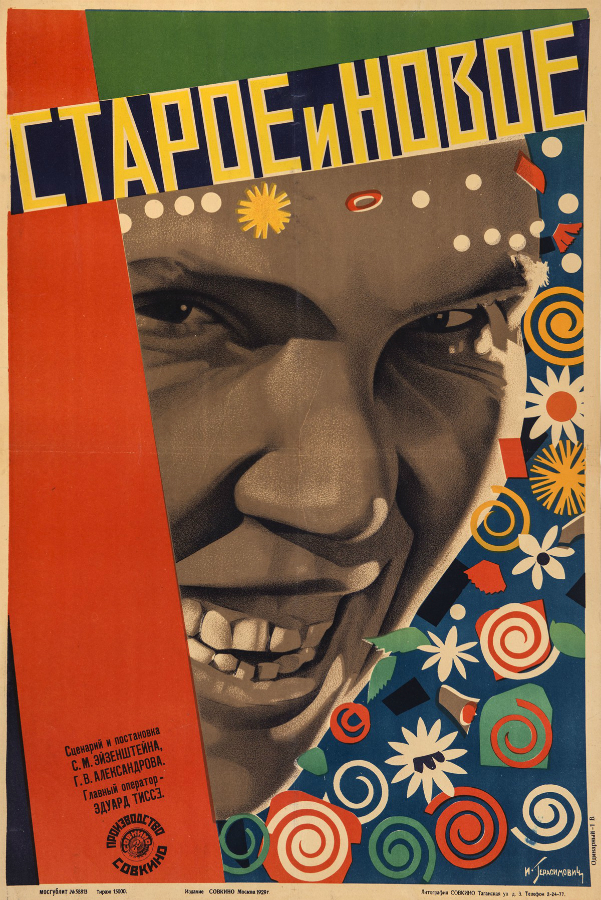

Pioneering Marxist film critic reviews Sergei Eisenstein’s ‘ 1929 film ‘The Old and The New, (The General Line).’ A link to the film here.

‘The Old and the New’ by Harry Alan Potamkin from New Masses. Vol. 5 No. 12. May, 1930.

The third period of the Soviet kino begins! The first period, still persisting in occasional films, is the period of Polikushka, the plight of the individual; the second period which will recur in the third, is the period of Potemkin to Storm Over Asia, the period of the physical and the retrospective. The vigor of this second period endows the film of the third with essential health. Into this sound body, upon its firm strength, is built the new kino of reflection and prospect, education toward the future.

The film which proclaims this new era is The Old and The New, (The General Line), the General Peasant Policy tract by Eisenstein. Yes, a tract — upon tractors. Eisenstein was confronted with a problem which differed entirely from the compact moment of Potemkin or the historical canvas of Ten Days. He was to make a piece of social agitation that would stimulate to action and that would be informative of what the new collective peasantry would gain by rejecting individualism.

He was talking to a people–of simple and immediate motivations, of not fully criticized suspicions and of certain precise experiences. He was giving them also a moving picture and they, of simple backgrounds, would want a picture that entertained with folk-simple drama. Their logic was a narrative logic, an elementary sequential logic of ideas expressed in a logic of images. Eisenstein’s intention was to produce by this expression of ideas in images a logic of dialectics: The Old and The New! This film is a first statement of the endeavor to bring the philosophic element into the cinema, an endeavor Eisenstein promises to realize fully in his rendering of Marx’s Capital.

The problem: an educational and, an agitational conviction, a simple narrative, a folk mood…to be made into a film. How was it done?

Thus: the philosophy, or ideological intention, is not kept a thing apart, but converted into the persuasive, folk narrative. Once having recognized and established the problem, the director determined upon a structure. It is the structural soundness and variety of The Old and The New that makes it a film superior to A Fragment of an Empire, which has the elements of the Eisenstein film but lacks its structural rhythmic coordination.

Machinery and the bull-progenitor are the impetus of the film. They are the subject’s concentration–points and the film’s pivots. How immediately Eisenstein transmits the problems to the peasants! In their terms, in their experience.

The bull is to be wedded to the heifer. This is the splendid ritual of earth. The community garlands the bride and Fomka the groom. The guests wear garlands. And the black kitten, the bridesmaid, wears too a wreath. The marriage is fulfilled.

The record on the screen is masterly in camera–alertness and impact-mounting. The gaiety of the preliminaries moves leisurely to a fierce accumulation in the rush of the bull and the cow rearing to receive him.

But the kulak bribes peasant stool-pigeons to poison Fomka. Gloom, despair weigh upon the community. Martha Lapkina, the film’s bright-eyed symbol of the collective, falls upon the black earth weeping the death of Fomka. The calf nestles to her: he is hope!

The peasants have just participated in an ignominious religious ritual, from which they have arisen to suspect the priest. From this agitation to the agitation of the agricultural director they go, suspicious of all that distance, heaven or Moscow, sends. Heaven sent a black-frocked priest and a humiliating ritual. Moscow sends a talkative man and — a suspicious milk-separator. The milk-separator invites, however, curiosity as well as suspicion, and when its entrails move, its udders pour—Abundance! Martha bathes in the benediction of Milk. The clouds burst and pour Milk! Eisenstein repeats in the suspensive and glorious movement of the separator’s mechanism the success of the Potemkin’s getting underway. But here it has more than a moment’s meaning: it is the future, the new world.

A tractor is bought. Eisenstein does not spare a third enemy of the people — kulak, priest, bureaucrat — the clerk who holds his soul together with red-tape. But he gets back as soon as he can to the tractor.

The operator of the tractor has dressed himself in an aviator’s helmet, goggles, wind-breakers, celluloid collar and ties askew. But tractors are run otherwise. The peasants, their doubt substantiated, return to the hut and the horse. Martha stands by. The chauffeur removes his coat, his hat, his goggles; he is in shirtsleeves, under the tractor. The trouble is discovered. He needs a cloth. Rip goes Martha’s skirt. She submits laughing, masking her eyes for modesty. Virginal Martha, fecund Martha! The tractor moves and Martha rides with the engineer. Hoo-rah! a line of trucks is tied onto the monster. The peasants leap upon their steeds, and the procession winds over the furrows. ALL RUSSIA IS TRACTOR-BLOSSOMING!

This film is a film of wit, folk-humor, shrewdness, optimism, clarity and point, ingenuity, a structurally harmonized duality of viewpoint: of the objective builder and thinker, and of the narrative. It forestalls the objection of two different approaches by its integration of the two toward a single end: COLLECTIVISM! The Old and The New is of greatest importance to the future, not only of the Russian’s film, but of the world’s cinema. It proclaims the period of reflection and prospect in the Soviet kino, and enters, as a contributor, the evolving era of the cinema of the world, the cinema of contemplation and inference.

The New Masses was the continuation of Workers Monthly which began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Communist Party publication, but drawing in a wide range of contributors and sympathizers. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and The New Masses began. A major left cultural magazine of the late 1920s to early 1940s, the early editors of The New Masses included Hugo Gellert, John F. Sloan, Max Eastman, Mike Gold, and Joseph Freeman. Writers included William Carlos Williams, Theodore Dreiser, John Dos Passos, Upton Sinclair, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, Dorothy Parker, Dorothy Day, John Breecher, Langston Hughes, Eugene O’Neill, Rex Stout and Ernest Hemingway, Artists included Hugo Gellert, Stuart Davis, Boardman Robinson, Wanda Gag, William Gropper and Otto Soglow. Over time, the New Masses became narrower politically and more journalistic in its tone.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/new-masses/1930/v05n12-may-1930-New-Masses.pdf