Reflections from Phillips Russell as he walks the 1914 Columbia University exhibit of the work of Belgian artist Constantin Meunier, his cultured proletarian eye astutely observing.

‘Constantin Meunier Sculptor of Labor’ by Phillips Russell from The International Socialist Review. Vol. 14 No. 11. May, 1914.

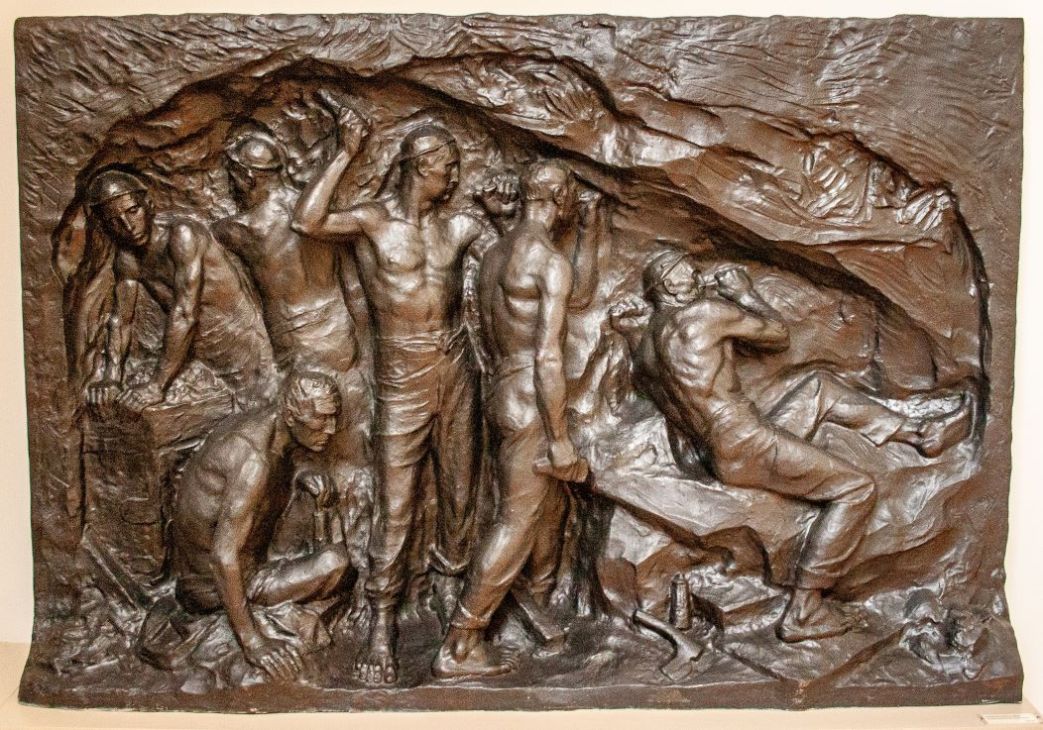

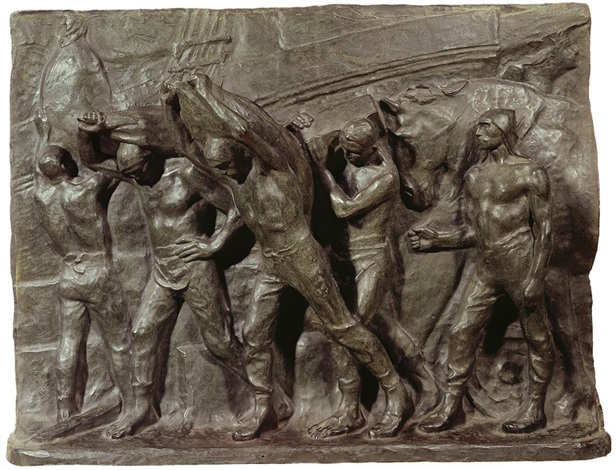

AN EXHIBITION of the works of Constantin Meunier, sculptor and painter of workingmen and women, recently was held in the Avery Library of Columbia University, New York. Great crowds attended. This fact is not without significance. Thanks to widespread and continuous agitation, to great and revolutionary strikes, the world is becoming acutely aware of the workingman just now and wishes to know more about the animal. Any one who can explain the creature and make him plain to the middle and upper class public is sure of a hearing. Meunier died in 1905, but America discovered him only last month. Ten years ago these sculptors would have been ignored except by art critics and chronic gallery visitors. Now they are the rage. How much of this interest is due to Lawrence and Paterson, to West Virginia and Trinidad, to Calumet and Little Falls, can only be surmised.

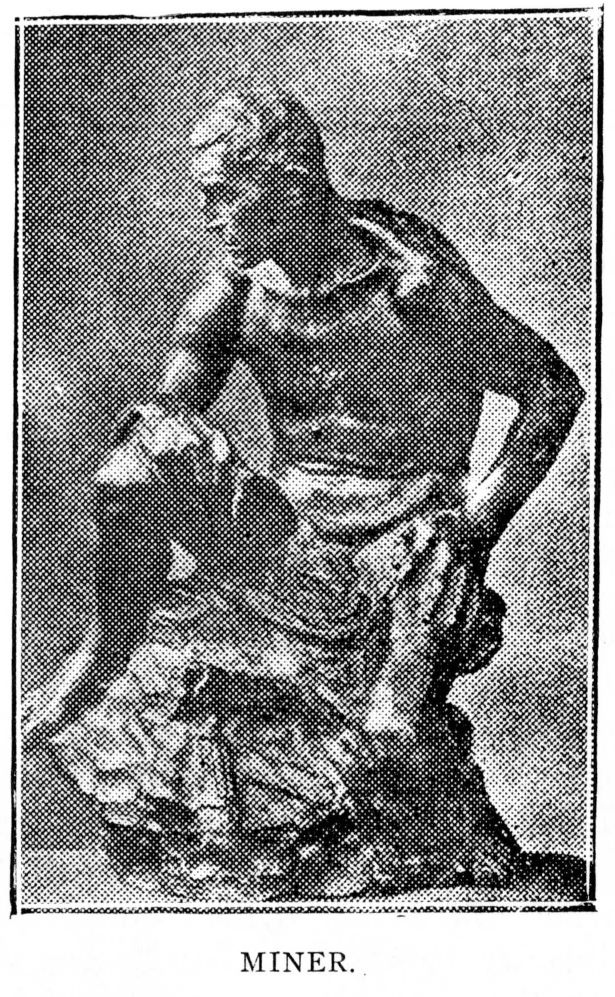

I am no art critic. Hence my views on the subject of Meunier may be of interest. I heard the exhibition spoken of rapturously. But I felt a little disappointed. The sadness, the grimness of labor were there, but Meunier’s workingmen are too clean-limbed and athletic, too vigorous, too well-poised.

If I were a sculptor or a painter and wished to depict a workingman, I would not select for my subject a burly iceman or a husky longshoreman who stands out among his fellows because of his unusual physique. I should select an east side sweatshop worker, shuffling toward his child-crowded tenement at 6:15 p.m., pausing occasionally to discharge his tubercular sputum into the gutter, his skin pale and corpselike, blue from lack of red-blooded food, on his head a ridiculously low-crowned derby pulled down over his ears, in his eyes the misery of years. He isn’t beautiful, but he is labor.

Perhaps this criticism isn’t fair to Meunier. He was born in 1831 and his observant years were passed in an era when the hand tool still prevailed, when the proletarian worked in the open air, and when labor might truly be said to have some dignity.

But the ten-acre factory, the eight-story loft building, removed that dignity long ago, along with everything else the workingman had, including his wife and children, his health and his life-blood.

Meunier, too, was a Belgian and it may be that the mine and the dock haven’t yet gotten in the deadly work that they have over here. Still, the Belgian mines must have progressed somewhat along modern lines of “efficiency” for Meunier has one stark little piece labeled “Fire Damp.” On the ground lies a bare-footed miner, and even in the bronze Meunier lets us see that his dead eyes are turned backward and upward. Above him hovers a gaunt woman, her attitude revealing that her grief is dumb. And even here I find an objection.

The little bronze piece provokes pity instead of anger. Meunier shows a tendency in bronze toward what are called “Sob Stories,” as so many of our wielders of the pen do. The objection to sob stories is that they cause more fortunate proletarians to exclaim, “Thank God that didn’t happen to us,” and so cause them to hug their chains more tightly, under the delusion that after all they are better off than others and hence ought not to complain.

Though Meunier makes his toilers athletic he doesn’t give them intelligence. Some of his men are almost apish in aspect. They walk with a shamble. Their foreheads are low, their ears set high. Was Meunier right in making his wage slaves appear to be little better than apes? Some might reply: yes, else they wouldn’t be wage slaves.

Meunier’s workingwomen are more true to life than his men. “The Mine Girl,” is hard to distinguish from a man. Her breasts are flat, her waist large, her limbs muscular. This figure shows that Meunier was a keen observer, it being a fact that the marked differences in the physical characteristics of the sexes tend to disappear when men and women work side by side at the same task. Meunier shows us here how our masters are reducing us to that dead level which they pretend to abhor.

The artist’s treatment of women would indicate he was a believer in the equality of the sexes. His female figures are without coquetry or skittishness. They smile simply. Their gaze is fearless. They walk with a free stride; they do not seem to sorrow over the fact that the capitalist has taught them woman’s place is in the mine.

In practically none of Meunier’s faces is there any sign of revolt. They are pathetic, apathetic, brooding, sometimes even powerful, but almost never rebellious. Perhaps he is dismally true to life in this respect, but one discontented countenance, even an ill-tempered one, would be a welcome contrast in this row of submissive, quiet figures.

We are not told much of Meunier, except that he had a long and racking struggle with poverty and was but ill appreciated.

He taught in an art school for a while and then spent some time in Spain but returned. to Belgium where he lived in one of the colliery districts, whence he gained his knowledge of proletarian life. A bust of him indicates he was a poet and dreamer. His features are large but as patient as one of the old Hebrew patriarchs.

An art critic in writing of the exhibit says many visitors left it with tears in their eyes. That’s the trouble. We’ve been weeping over the prostrate head of the workingman all these years, but all the tears in the universe will never wipe away the system that makes him and keeps him a hewer of wood and a drawer of water. Perhaps more curses are needed and fewer tears.

The International Socialist Review (ISR) was published monthly in Chicago from 1900 until 1918 by Charles H. Kerr and critically loyal to the Socialist Party of America. It is one of the essential publications in U.S. left history. During the editorship of A.M. Simons it was largely theoretical and moderate. In 1908, Charles H. Kerr took over as editor with strong influence from Mary E Marcy. The magazine became the foremost proponent of the SP’s left wing growing to tens of thousands of subscribers. It remained revolutionary in outlook and anti-militarist during World War One. It liberally used photographs and images, with news, theory, arts and organizing in its pages. It articles, reports and essays are an invaluable record of the U.S. class struggle and the development of Marxism in the decades before the Soviet experience. It was closed down in government repression in 1918.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/isr/v14n11-may-1914-ISR-riaz-GR-ocr.pdf