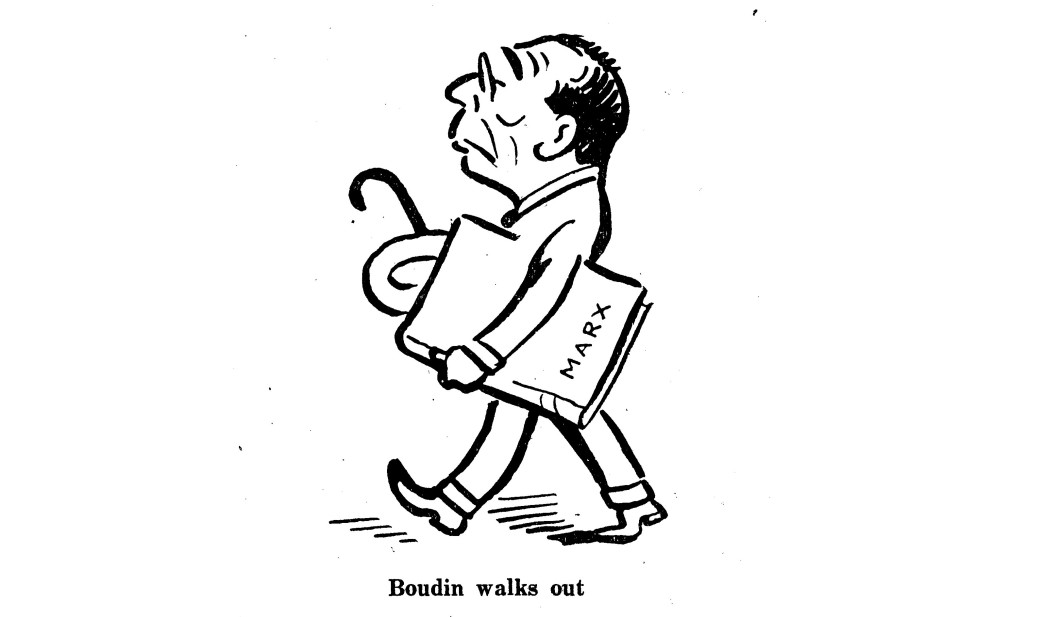

A brilliant intervention by Louis B. Boudin into the fight within the Socialist Party over the ‘theory’ of sabotage which would see William D. Haywood, and the forces he represented, become ‘incompatible’ with the Socialist Party.

‘Theory as a Social Force’ by Louis B. Boudin from New Review. Vol. 1 No. 7. February 15, 1913.

The other day the Call published an editorial article on “Theory as a Social Bogeyman.” The author of the article points out the curious fact that there is a vast difference to the mind of the “average bourgeois” between a “crime” committed for its own sake, so to say, and the same action committed in pursuance of a “theory” which requires or justifies its commission.

Our author further observes that:

“You can do about what you darn please in the way of sabotage or divorce or gambling or blackmail or a hundred other things, provided you don’t publicly proclaim that you have a theory that justifies them. When you do that the action that never took place becomes infinitely more terrifying than a thousand that actually occur, but which the perpetrators disclaim to hold any theories about They do them and say nothing, and nobody ever gets very excited. The law punishes them, to be sure, when caught, but if they told the judge that they did so because of a “theory” they hold, their punishment would be increased tenfold.”

He then proves his thesis from our every day experience:

“Every week or so some alleged “black-hander” throws a bomb into an Italian store or tenement hallway for purpose of blackmail. The matter is disposed of in a short item of half a dozen lines, perhaps a dozen, if somebody is killed. The wretched little Silverstein, who some years ago threw his pretty little bomb in Union Square and killed himself and a bystander, got column upon column of space because he was described as an “anarchist,” and therefore was popularly accredited with a “theory” of bomb-throwing. The other day, according to the press, a bunch of striking waiters threw some bricks through the plate glass windows of the Hotel Astor. Whether this is true or not, nobody got excited about it. It could be disposed of in one short paragraph, and it was so disposed of. But let some one march up Broadway with one solitary brick in his hand and heave it through the hotel window, get arrested and use a “theory” to defend himself when before the magistrate, and what would happen? Why, the Sun and its contemporaries would use columns to describe the fearsome social menace of a man with a “theory” throwing a brick.”

And then our author proceeds to poke some rather clever fun at the expense of the stupid “average bourgeois” and his editorial mouth-pieces for being frightened at the bogeyman, Theory, while regarding with comparative equanimity actual Fact.

The phenomenon observed is undoubtedly true and interesting. But are the “average bourgeois” and his editorial mouthpieces really so stupid? Is the laugh really on them?

Let us see.

First of all; are the ‘average bourgeois’ and his editorial mouth-pieces the only ones who are afraid of that bogeyman, Theory? How about the intelligent, class-conscious, proletariat and its editorial and other mouth-pieces?

In May, 1912, the representatives of the intelligent class conscious part of the working class of this country met in convention at Indianapolis. The convention was confronted with two important facts of the labor movement: One a live, actual one; and one of the bogeyman variety. The confession of the McNamaras and the revelations which preceded and followed it showed an alarming prevalence of the use of violence and the “criminal” destruction of life and property by organized labor in its struggle against organized capital. At the same time it appeared that a certain portion of the working class was beginning to incline to a theory which justified the use of violence and the destruction of property in labor disputes, although not in quite as reprehensible a form as that actually practiced by the McNamaras and their associates.

What did the convention do?

Why, it did nothing about the crime and violence that were actually committed by the McNamaras and their associates. But it got terribly excited about the alleged theories of Haywood and his associates. To use our author’s own phraseology, Haywood’s “action that never took place became infinitely more terrifying” than the McNamara’s “thousand that actually did occur,” because the latter acts belonged to the class about which “the perpetrators disclaimed to hold any theories.” The excitement into which the convention was thrown by that bogeyman, Theory, resulted in the adoption of some very stringent regulations— against the bogeyman, not against the actual Fact.

Art. II, Sec. 6 of the national constitution of the Socialist party strictly prohibits and penalizes the “advocacy” of crime, violence and sabotage. According to the supreme law of the Socialist party if a striking waiter or sympathizer heaves a brick through the plate glass window of the Hotel Astor he goes scot free, provided he holds no theories about it. But if he should attempt to justify his action by a theory, or even leave the brick alone but hold the theory, dire punishment will overtake him. “For”—says the national constitution of the Socialist party—”when you have a theory that justifies such actions, the action that never took place becomes infinitely more terrifying than a thousand that actually occur, but which the perpetrators disclaim to hold any theories about.”

Was the Socialist party convention simply stupid when it adopted “Section Six”? By no means. It may have been wrong we believe it was wrong—but it was far from stupid. And even less so are the capitalists when they look with unruffled countenance upon thousands of actual infractions of its laws and its morality, but “view with alarm” the advent of any theory that justifies such infractions. The fact is that a social theory is not a mere “bogeyman” but a tremendous social force. That is why the bourgeoisie spends such enormous amounts of money and energy to combat all Socialist theories, particularly that body of theory known as Marxism. That is why it supports innumerable institutions of learning and other organs of public opinion whose chief function is to expose the “fallacies” of the Marxian theory. That is why the discovery of any alleged “contradiction” in that body of theory, and every negation thereof or departure therefrom by any portion of the working class are hailed with so much delight by the capitalist class, particularly its more intelligent spokesmen. And that is also why many of its cleverest spokesmen have taken to scientific nihilism, attempting to shield themselves against the menacing theories by the denial of all theory.

But the menace of certain theories does not consist merely in their power as a weapon in the social struggle, but even more so in the symptomatic relation which they bear toward that struggle. The appearance and spread of a certain social theory is the expression of certain social and economic changes which are taking place in the body politic. Notwithstanding the fact that its apologists are constantly endeavoring to disprove the correctness of the Materialistic Conception of History, the capitalist class feels instinctively that this menacing theory is correct. It feels in its bones that these menacing theories are the translation into ideas of very substantial and material changes of social relations, consequent upon deep-seated economic changes, and foreshadowing revolutionary shifts of social power.

Far from being stupid, the capitalist class displays remarkable sagacity in appraising “crime” and theories justifying “crime” at their true respective worth. “Crime” as “crime,” that is, the infraction of laws the binding force of which is not denied by the infractors, has no social significance whatever, except in so far that a multiplicity of “crime” shows a diseased condition of the social organism. But a theory justifying certain “crimes,” or rather denying the binding force of the laws declaring certain acts to be “crimes,” shows the advent of a new morality, the rise of a lower class in revolt “Crime” in the ordinary acceptation of the word, is always an individual act. Even the so-called McNamara “conspiracy” was the act of the individual conspirators, notwithstanding the great number of persons involved and the even greater number of persons who, although not directly involved, were privy to it by shutting one eye upon the doings of the “conspirators.” This crime did not, therefore, in any way menace the existence of the capitalist social order. The capitalist system can take care of its criminals through the regular channels—courts, sheriffs, jails The McNamara affair therefore, notwithstanding its magnitude, caused only a ripple of excitement in the organs of capitalist public opinion, some demands for a strict enforcement of the “criminal laws” here, and some sad reflections and searchings of heart there. The latter were due to the fact that the magnitude of the affair showed to the capitalist class the diseased condition of its system, in this country at least. Many a reformer and progressive must have thought that the powers that be in this country must have driven things too far when so many conservative trade-unionists, thorough believers in our system of law and order, were driven to commit such serious infractions of its rules and regulations. This was clearly a case for reformation of abuses. But there was no cause for serious alarm.

But it is quite different when instead of a widespread “conspiracy” for the secret individual infraction of “law and order,” there is a widespread open defiance of our whole social system in the name of a Theory. A theory, and particularly a widespread theory, is the offspring of the intellect and moral consciousness of masses in their mass-capacity. A theory which denies the accepted canons of morality and runs counter to the established principles of “law and order” is the accompaniment of a class revolt. Its mere appearance shows the inception of that revolt. Its spread shows the growth of that revolt.

Surely, here is “menace” enough.

The New Review: A Critical Survey of International Socialism was a New York-based, explicitly Marxist, sometimes weekly/sometimes monthly theoretical journal begun in 1913 and was an important vehicle for left discussion in the period before World War One. Bases in New York it declared in its aim the first issue: “The intellectual achievements of Marx and his successors have become the guiding star of the awakened, self-conscious proletariat on the toilsome road that leads to its emancipation. And it will be one of the principal tasks of The NEW REVIEW to make known these achievements,to the Socialists of America, so that we may attain to that fundamental unity of thought without which unity of action is impossible.” In the world of the East Coast Socialist Party, it included Max Eastman, Floyd Dell, Herman Simpson, Louis Boudin, William English Walling, Moses Oppenheimer, Robert Rives La Monte, Walter Lippmann, William Bohn, Frank Bohn, John Spargo, Austin Lewis, WEB DuBois, Arturo Giovannitti, Harry W. Laidler, Austin Lewis, and Isaac Hourwich as editors. Louis Fraina played an increasing role from 1914 and lead the journal in a leftward direction as New Review addressed many of the leading international questions facing Marxists. International writers in New Review included Rosa Luxemburg, James Connolly, Karl Kautsky, Anton Pannekoek, Lajpat Rai, Alexandra Kollontai, Tom Quelch, S.J. Rutgers, Edward Bernstein, and H.M. Hyndman, The journal folded in June, 1916 for financial reasons. Its issues are a formidable and invaluable archive of Marxist and Socialist discussion of the time.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/newreview/1913/v1n07-feb-15-1913.pdf