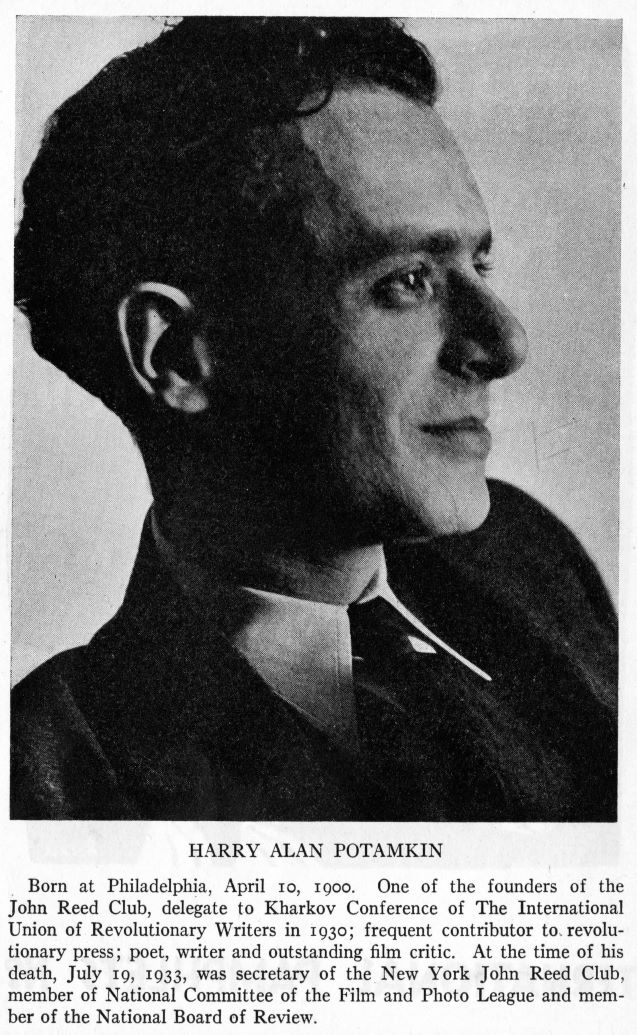

In another fine essay, pioneering Marxist film critic Harry Alan Potamkin gives a class accounting of the film industry.

‘Who Owns the Movie?’ by Harry Alan Potamkin from Workers Theatre. Vol. 1 & 2. Nos 11 & 1. February & April, 1932.

The movie was born in the laboratory and reared in the counting-house. Today it is the slave-child of finance capital. Wall street dominates it. Its direct managers, the producers in Hollywood, are all as far from the needs of the audience as Hollywood is from New York. For, who is the audience? Back in 1909 a Harvard professor recognized the movie-fan as “the self-respecting petty-bourgeoisie and the workingman”. In 1916, the pioneer American film-director D.W. Griffith, called the movie “the laboring-man’s university”. Nine years later the American writer, James Stevens, designated it as “the laborer’s art”. In brief, the larger audience of the movie is the workingman and the member of the middle-class who touches upon the proletariat. He supports the movie, art of “the machine age”, of corporate economy, of mass-production. And the producer? He is generally a former shopkeeper, manufacturer, money-lender, the newly-rich. His “ideals” are the themes and tones of the film.

At first the producer was one individual, the distributor another, the exhibitor a third. But as business became more and more consolidated, as the trust began to form, the movie too, being an art controlled by business, became more and more consolidated into fewer and fewer hands. Producer-distributor-exhibitor became one. Soon they were one in the hands of Wall Street. Having completed this trustification for mercantile and financial purposes, the movie had to extend centralization into the field of ideas. The Hays organization was formed, the moral, intellectual, political concentration of the movie industry. Today the movie is body and soul directed from a central point to influence the mind of the audience.

Why does the dominant class expend all this effort in the film? The movie is the most generally enjoyed amusement. It is the education of the masses.

People remember best what they see. Sixty-five percent of what we believe has come to us thru the eyes, twenty-five percent thru the ears. The movie is today sound and sight, 90%. Add to this the fact that the movie is not a frozen image seen once and quickly but something which retains us for two hours at a time, something we can “feel” and the influence is very close to 100%. It is the mass-art, the mass-amusement, the mass-education. And therefore the dominant class wants more minute control of it. In direct proportion to the volume of the influence is this control. A play is seen by a limited number; the control over it is limited. A book is read by more than see the play but by fewer than see the film; therefore the control over it is greater than the control over the book and less than the control over the film.

Marx and Engels have said, in The Communist Manifesto, that the class that controls production will pay only that wage which will assure the desired production. In brief, the minimum. Similarly, the class that controls movie production will present only that idea which will assure passivity in the audience. When the movie was not yet fully under central control, Upton Sinclair’s novel, “The Jungle”, was produced. The company that produced it was allowed to go bankrupt. And we must remember also that “The Jungle” has been persistently read down as a tract for pure food. The dominant class has also an interest in that.

The movie was very early used in self-defense. In 1906, when “The Jungle” appeared as a novel, the Armour meatpackers took a film of their plant made in 1900, dusted it off, and released it as an “answer to the accusations of the novel.

Another novel by Upton Sinclair, “The Money Changers”, which explains the panic of 1907 as having been manipulated by J.P. Morgan, was purchased for the screen by Ben Hampton, a personal friend of Sinclair. Hampton promised to preserve the text and spirit of the novel. When the film appeared it was a melodrama about Chinatown. Hampton has just published “A History of the Movies”, but he has not included this incident.

Very early, in fact the same year as the film of “The Jungle”, pictures began to appear making a hero of the scab, preaching against violence and for the support of the church in cementing relations between labor and capital. Today, even the existence of such a hyphen as labor-capital is not admitted.

The Universal producers are to make a film called “Steel” (not John Wexley’s play). The steel trust has consented to loan their foundries as a setting, provided that no mention is made of the relation between labor and capital. The producer is on the defensive; his class is in a critical position. The Fox company forbids any newsreel clips of breadlines or “anything that might possibly be construed as Bolshevist propaganda”.

Might not, one may ask, the director, the creative artist of the screen, bring another note into the movie? Well, who is the director? Generally speaking, he has been an actor, a newspaperman, a baseball-player or the like. His experiences and interests, the bribes paid him, keep him very far from the audience for whom he is making his films. And even if he wanted to make a film more critical of conditions, he would be sat upon.

There’s the case of the film “Touchdown,” which a young director wanted to make as an indictment of college football. It starts out that way, but the producers took the film in hand and made it end as a whitewash of the coach and college. The young director, because of his opposition, was not even thanked. His name did not appear on the screen. “Queer People”, a novel ridiculing Hollywood was bought by a rich young producer. So threatening has been the central control, that no actor has dared to accept a part in it, and the producer has laid the film aside. He has even refused to let the film be made in England. “Once in a Lifetime”, another satire on Hollywood, almost received the same treatment, but Laemmle of Universal has promised the film won’t hurt anyone’s feelings. Hollywood, don’t forget, is vested interest. It is a closed circle in which all the people live according to the fables they see and act in on the screen. They are going to preserve and protect their property even if it means keeping new energies from entering. They conspired to keep out the young Soviet director, Eisenstein. The actors of the screen, the golden trademark of the movie, young upstarts or old fogies, live in the atmosphere of their own perfumes. They certainly cannot understand the needs of the audience. Yet it is their “personalities” that are fed to the workers who go to the movies!

Censorship.

In the control of the movie, the political instrument of censorship is used. There are, broadly speaking, two forms of censorship: censorship at the source, and censorship at the point of distribution. The former operates thru the Hays organization, the latter thru the Board of Censors. In the latter instance, censorship is severer with productions from independent studios than with the films from companies in the Hays organization; severer with foreign films than with domestic; much harder on pictures from Soviet Russia than on pictures from capitalist lands; and very drastic where pictures are submitted by a working-class organization. In the last two categories we have several outstanding examples: the suppression in New York of the Soviet satire, Bed and Sofa, a charming and wholesome treatment of the “eternal triangle”; the suppression in Philadelphia, of “Potemkin” and the brutal deletions from “Seeds of Freedom” which made it impossible to release the picture; the New York censors’ vandalistic “suggestions” on “Volga to Gastonia”, a proletarian production. The instances are manifold, but we need not name more. The routine reasons given–immoral, inciting to riot, etc.–are not exercised toward condemning the salacious pictures featuring, let us say, the sex adventures of a Joan Crawford, nor do they become alert toward the suppression of a counter-revolutionary picture like “The Spy”—anti-Soviet or “The Shanghai Express”–anti-Chinese. We recall, since this latter film lifted many of its pictorial devices from the Soviet film “China Express” that the Russian picture was looked at by the censors at least twice. After a week at the Cameo, “China Express” was returned to the censors. It happened that March 6, 1930 intervened during the public showing of the film, and the censors, working with the Hays organization, became an immediately active political agent. “China Express” was withdrawn while the sentiments aroused by the unemployed demonstration and the attendant police brutality were acute. This is collaboration between the movie-business itself and the state censor.

The movie-business censors its own films. I have already indicated how the very class-nature of the movie-producers accepts only its own ideas and ideals as movie material. But there is a sharp illustration of such practice in the case of the newsreel. We all know how much news of importance gets into the newsreel. But we all do not know that certain of these news-pictures are suppressed even after filming: this is the movie-barons’ way of saying “All the News that’s Fit to Print”. Now, the censors have no jurisdiction over newsreels, since these are pictorial newspapers in their way–at least theoretically–and are current dispatches. But there is still Will Hays. Thru his office the following news-pictures were suppressed, even destroyed: The Sacco-Vanzetti items; The March 6th unemployed demonstration; The May 1, 1930 demonstration; The Hunger March–and others. Fortunately, the Workers’ Film and Photo League has records of these.

The movie-bosses comprehend the significance of the newsreel. Therefore Fox orders all house managers to delete all newsreel clips showing “controversial matter, breadlines and anything that might be taken for Bolshevist propaganda”. The story goes that this order was stimulated by the mixed reception at a Fox house to a clip showing Mussolini, but Mussolini still parades over the Fox screen.

And when the news value of a clip is so intense that the company hasn’t the financial heart to delete it, the company can modify the effect so:

Graham McNamee, the Universal squawking reporter, comments in one newsreel on two labor-capital items: he supplements a clip showing the railroad labor-misleaders signing the wage-cut with a remark as to how beautifully things slide when “men are men…without seeing red”; and to a clip of the Bronx rent-strike he adds this touch: “…and another the red riot went the way of all flesh”. The same mercenary comments on a scene of Chinese coolies eating rice from a floor with their fingers: “The lowest form of humanity”.

We should learn something from this technique. “Pictures don’t lie we are told. This is a platitude: pictures can be made to lie by a re-arrangement, by captions, by oral remarks. Now, it is our business to make them tell the truth: let us show ‘Erbert ‘Oover handing out the gaff, and comment from the point of view of actual facts on what the President represents. Let us use the common newsreel item and make it speak the truth.

The matter of censorship becomes complicated. Various agencies want to control it. Today there is a three-cornered fight for the Federal Council of Churches control: the Hays organization, of Christ, the Presbyterians. The last desire a federal or national censorship. And they are not alone. With them there are such organizations as the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, Baptist and Methodist Episcopal missions and the National Grange. The fight for such centralized censorship is not new. On March 20, 1914 Canon Chase appeared before the Committee on Education of the House of Representatives and opposed the unofficial National Board of Censors, not National Board of Review. This organization, founded by the People’s Institute in 1909, was against political control of the film, its slogan: Selection not Censorship. In recent years it has been rendered less effectual by the establishment of the Hays organization which appropriated in true demagogic fashion the National Board of Review’s slogan. It serves as a decoy or smoke-screen.

As for Canon Chase, only this year he left the pulpit to fight more energetically for “moral reform”. Let us understand this term “moral”: it is a wedge into political control. Hays, Chase and the others advocating one or another kind of censorship are not fundamentally at odds; each wants the immediate profits of such control. Actually Hays is an elder of the very church, the Presbyterian, opposing both state and studio censorship. But shrewdly he has affiliated with himself on his Committee on Public Relations, the National Catholic Welfare Conference and the International Federation of Catholic Alumnae, the Daughters of the American Revolution, the Boy Scouts, the General Federation of Women’s Clubs, the Russell Sage Foundation, the National Congress of Parents and Teachers, the National Educational Association, the American Library Association, the Y.M.C.A., and the National Recreation Association–school, church, playground, club, etc. Then the coalition was started, labor was “represented” by the A.F. of L. demagogue, Hugh Frayne, lately included by Matthew Woll in his 100 citizens to combat communism. But the A.F. of L. is perfectly content to let Hays do the job of making the worker a “100% American”.

Less actively associated with Hays has been the liberal church body, the Federal Council of Churches. Peeved by the disrespect shown to it by Hays, this group has attacked him but not very clearly. Actually speaking, this group serves a social-fascist purpose in the movie which will become more tangible as time goes on.

In the meantime the out-and-out fascist body led by Canon Chase has been able to get itself heard in Congress where the Hudson Bill awaits decision. This Bill, amid the usual decoys of moral supervision, places the real aim of capitalist control–the suppression of films that “ridicule or deprecate public officials, or other governmental authority, or which tend to weaken the authority of law or offend the religious belief of any person; or which unduly emphasize bloodshed and violence”. This is obviously class legislation and really nationalizes the Hays code. The question is solely as to which reactionary agency shall directly benefit from the profits of control.

Our answer to that question is to fight all forms of censorship. We must fight against national censorship–which has Hearst support–because it will mean the positive elimination of films from the Soviet Union, films sponsored by revolutionary labor and even films by possible courageous independents. The more split-up censorship is, the better we can fight it. At present some states, like New Jersey, have no Board of Censors. encourage such a condition. We know that censorship is inevitable in a class society and that defense of “free speech” is either idealistic or tactical. Idealistic defense betrays itself and betrays the proletariat, but a tactical working-class attack on censorship is part of the very class struggle itself. We must oppose all attempts to extend or concentrate censorship, and we must organize to fight every act of the censor reprehensible to the working class. That should be a major task of the cultural bodies like those of the W.I.R, the Workers’ Cultural Federation, the John Reed Club, etc. Don’t let the censor get away with it!

Workers Theatre began in New York City in 1931 as the publication of The Workers Laboratory Theater collective, an agitprop group associated with Workers International Relief, becoming the League of Workers Theaters, section of the International Union of Revolutionary Theater of the Comintern. The rough production values of the first years were replaced by a color magazine as it became primarily associated with the New Theater. It contains a wealth of left cultural history and ideas. Published roughly monthly were Workers Theater from April 1931-July/Aug 1933, New Theater from Sept/Oct 1933-November 1937, New Theater and Film from April and March of 1937, (only two issues).

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/workers-theatre/v1n11-feb-1932-Workers-Theatre-NYPL-mfilm.pdf

PDF of issue 2: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/workers-theatre/v2n1-apr-1932-Workers-Theatre-NYPL-mfilm.pdf