Thurber Lewis with a fine essay on the ‘Klan War’ in Southern Illinois. A region, perhaps more than any other in the country, that had the best and worst of the U.S. labor movement competing for leadership of the class. The conflict between radical miners, gangsters, coal operators, the U.M.W.A. leadership, and the Klan for control of the Southern Illinois coal fields was complicated by the splits within the left union forces, race, language, nativity, and guns. A long, roiling civil war within mining communities lasted two generations as the many foreign-born miners resisted the Klan despite their leadership. The mines and unions of Southern Illinois are gone, it remains a seat of reaction.

‘Class and Klan in Herrin’ by Thurber Lewis from Workers Monthly. Vol. 4 No. 5. March, 1925.

WILLIAMSON is a coal digging county. It is dotted with mines. The bulk of the population is mining; the balance is small farmer and business. One has only to talk to the miners to see that half or more are foreign born. Most of the foreign diggers are Slavs and Italians. A distinct southern drawl marks the speech of the greater part of the American stock. For the most part, these latter originated in Kentucky and Tennessee. Some of them come from the mountain race of tobacco-chewing, cussin’, straight-shooting White Mule distillers who have gained the reputation of being fond of firing off guns at each other. Some drifted in from the southern lowlands, the habitat of the “poor whites,” who remain to this day bewildered by the onrush of industrial progress.

The miners in southern Illinois, where Williamson County is, are organized one hundred per cent. Many years of strike and struggle have given them their job control. You can’t work in the Illinois mines unless you are a member of the United Mine Workers of America. And the miners are not going to let their union be taken away from them without a fight.

Those miners are proletarian to the bone. The foreign born diggers have a long proletarian ancestry. The Americans are new to wage-slavery; the generation before this and much of the present were sons of the soil, but it doesn’t take many years at heaving black diamonds a thousand feet under to make proletarians—and real ones. One doesn’t have to be in Williamson County more than a few days to learn that there is more to the struggles there than just klan and antiklan.

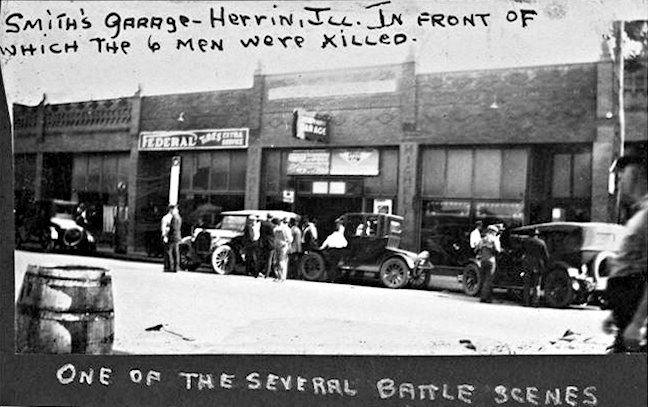

The open-shoppers learned a lesson in Williamson County in 1922. The Lester strip mine, outside Herrin, tried to run with scabs and gunmen during the big strike of that year. The gunmen got reckless and shot a couple of strikers. Not many of them got away to tell the story. After the smoke cleared a number of miners were brought to trial. The Illinois Chamber of Commerce gave $50,000 for the purpose of prosecution. Most of the county officers were old miners. No one was prosecuted.

Why the Klan Came.

The lesson the open-shoppers learned was that frontal attacks on the miners of Williamson County won’t work. They have tried force and found the miners ready to fight back. The solid organization of the miners remains a barb in the side of the employers. If they can’t break the morale of the men one way they try another. They are trying another way now. The objective is the breaking up of the coal-diggers’ unions in southern Illinois; they have singled out Williamson County to start in because that’s the storm center. The medium they are using to turn the trick is the ku klux klan.

There are no more killings and there is no more liquor drinking in Williamson County than in any other southern Illinois coal county. Yet the ku klux klan decided that Williamson must be “cleaned up” at all costs—Williamson which had shown it could fight back when the employers launched an offensive against the miners. Why should the ku klux klan suddenly get busy in the neighborhood of Herrin, where the Lester strip mine is? The reason is that the klan is being used in a well-defined move to break down the organization and resistance of the miners.

The ku klux klan slipped into Williamson County on padded feet not long after the trials in Marion, the county seat. It worked silently. It gathered in some farmers, poolroom bums, preachers, boys-about-town looking for excitement, bankrupt business men and added to the lot a band of somewhat disreputable importees who were experienced hipshooters. The old-timers with feudist blood in their veins saw the chance to take their Winchesters off the wall again. The “purist” element saw an escape for their suppressions and an opportunity to show the “dam furriners” where to get off at. Hard-put-to-it, cockroach business men breathed easily at the thought of being released from the debts that wouldn’t let them sleep nights. And the men of God held out open arms to this mysterious stranger which, they had heard, jammed pews in other places. Nobody in the county talks more fervently of the klan than these narrow-souled preachers. The miners were off their guard. They were hoodwinked. What connection was there between them and this strange, and for a while, somewhat amusing movement that talked about “cleaning up” on Williamson? They are finding out.

Union Leader and Kluxer.

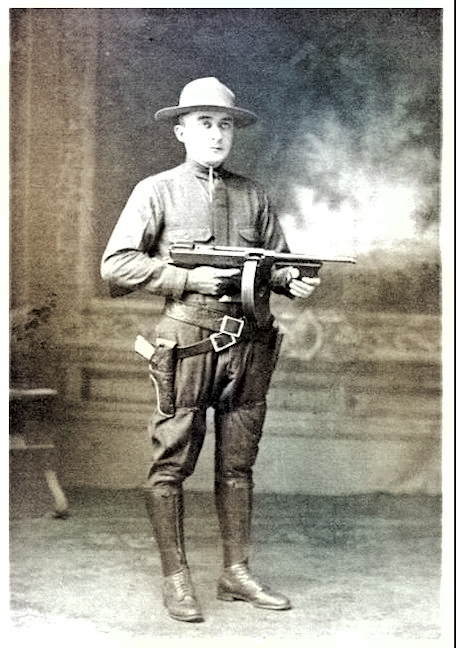

Two characters, Ora Thomas and S. Glenn Young, personify the clash of forces in Williamson County. Ora Thomas is a native of southern Illinois. He worked in the mines during most of his life and he joined the miners’ union when he was sixteen. His record as an active and influential member of the U.M.W. of A. is unsullied throughout more than twenty years of service. Not a miner for miles around but has a good word for Ora Thomas. He held many responsible positions and was sent as a delegate to many conventions. He was one of the leaders of the battle between miners and scabs at the Lester strip mine; now that he is no more, there is no harm in its being revealed. One story has it that he was the observer in the plane that soared over the mine during the affray. In any case it is certain he was one those who saw in the coming of the Chicago gunmen a threat against the miners’ organization and its chances of winning the strike, and that he was ready to play his last part in any trouble the imported gangsters might start. Such was the life of Ora Thomas.

It is not known where S. Glenn Young came from. Some say Texas, some say Kansas, and he used to say Kentucky. No matter. Everyone agrees he had a long career as a freelancing soldier of fortune behind him. His klan friends glorify his murders and say that he always shot in defense of virtue and his country. He himself was not without vanity and liked to tell of the thirty notches on his gun-handles. He told vivid stories of draft-dodger chasing and moonshiner hunting in the mountain fastnesses of Kentucky. He caught the imagination of the simple minded. But the one fact that has been established beyond question is that many years of his glorious career were spent in the services of scab-herding, strikebreaking agencies. Like as not, those notches represent thirty strikers.

Such was the life of S. Glenn Young.

These men represented the line-up in the struggle in Williamson County. They are both dead. On January twenty fourth, Ora Thomas stood up under the fire of Glenn Young and two of his bodyguards, shouting defiance and emptying his gun. Young and his men, who had started the shooting, dropped before Thomas went down with nine bullets in his body.

Out to Break Union.

But the struggle goes on. The klan is more domineering than ever. The miners are awakening more and more to the realization that the klan is in Williamson County to break up their morale and their union. The miners are beginning to sense the connection between the Lester mine and the klan.

The connection is direct and unquestionable. It has been quite conclusively proved that Glenn Young was one of the mine guards who escaped from the barricade in the Lester mine just previous to the battle. His later raids and searchings as leader of the klan “mop-up” forces, were discovered to have arisen out of a hidden anxiety to uncover machine guns, rifles and other material that could be used as evidence to re-open the mine riot trials in a country whose official machinery is controlled from top to bottom by kleagles and cyclopses.

Ora Thomas, leader of the embattled miners, was chosen from the beginning as a target and center of attack by Young and the klansmen. All the elements who were enthusiastic supporters of the prosecution in the trials following on the Herrin affair are found to be equally enthusiastic klansmen. Money was used by Glenn Young and his following in such liberal quantities as to indicate it came from other than local sources. That money was plainly poured out and the klan set on foot in Williamson County by interests bent on the disruption of the mine unions.

The klan fooled people down there at first all right. The openness of the county in the matter of booze gave the KKK a passable excuse for existence. The eighteenth amendment instead of meaning prohibition is merely a nuisance in Williamson County. Coal miners like their liquor hard. Facing the coal in the roasting heat of the lower veins calls for strong drink when the wearing day is done.

To make matters worse, the officials of the miners’ union are, as one person in Williamson said, “Either puss-footers looking for jobs or jellyfish and just plain scared.” Some are accused of being members of the klan. The miners lack leadership now that Ora Thomas is gone. But the coal diggers won’t be asleep much longer—leaders will spring up—they always do. The klan had little trouble finding a new leader when Young went. They are in complete control of the county now. They are working gradually and steadily up to the point where they will openly challenge the right of the mine unions to exist. Then the real fight will start.

The Herrin Lester mine affair and the raid shooting will be lost to memory in the melee that will follow when the miners awaken once and for all to the knowledge that the klan is out to take away their chief weapon—the union.

This story is lost if it is looked upon merely as the story of Herrin. It is the story of the class struggle the world over. The class struggle does not always present a picture of sharply divided opposing forces. It lurks in many hidden byways of social life. If in the end the class struggle expresses itself in plainly defined terms, it is often cloaked in the guise of movements apparently serving other ends. The fascist movement abroad is an example. At home, the American Legion, the klan and similar movements of the thwarted petty bourgeoisie and de-classed elements, are but heedless tools of the master class and implacable foes of the working class.

The Workers Monthly began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Party publication. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and the Communist Party began publishing The Communist as its theoretical magazine. Editors included Earl Browder and Max Bedacht as the magazine continued the Liberator’s use of graphics and art.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/culture/pubs/wm/1925/v4n05-mar-1925.pdf