Frances Fenwick Williams’ on-the-scene account from the midst of the Winnipeg General Strike of 1919.

‘The Winnipeg Strike’ by Frances Fenwick Williams from The Liberator. Vol. 2 No. 7. July, 1919.

THE strike at Winnipeg is a critical and significant event in the labor and political history of America, as a test of the attitude of the returned soldiers. Can they be used to break the strike, or can they be counted on to carry it to victory? Upon the answer to this question depends the immediate future of Canada, | I went to Winnipeg to find out. On my way I read in the newspapers the familiar comfortable assurances of the editorial column that the Canadian soldier was immune to “Bolshevik propaganda,” and that he was proving himself in Winnipeg, as everywhere and always, loyal first of all to the sacred cause of law and order.

There was nothing to be seen in the quiet and orderly streets of the strike-bound town, when I arrived, to show the contrary. But in the eminently respectable pages of the Winnipeg Citizen I found a piece of news which showed that the Canadian soldier in Winnipeg did not precisely conform to the editorial ideal. It was a description by Premier Norris of Manitoba, of his meeting with a delegation of returned soldiers at the. Winnipeg City Hall:

“The soldiers had presented a resolution to him in which they had expressed the desire that the government should try to bring about a settlement of the strike, and in which they had asked that “collective bargaining” be made compulsory. They had also complained of the action of the City Council in dealing with the police. They claimed that the ultimatum to the policemen was a serious mistake and that unless the ultimatum were withdrawn serious trouble would ensue.

“They also strongly objected to certain statements in the local press where it was said that trouble was caused, ‘not only by foreigners but also by a number of Scotch and English renegades.’ The premier had promised that he ‘would see that no similar statements would again appear.’ ‘I had to do this,’ he said, ‘as the soldiers were very angry and were in a very bad temper.’”

It seemed sufficiently clear that when the Premier of Manitoba “had to” do something because the soldiers were “very angry,” and confessed the fact very simply in the City Hall of Manitoba’s capital, something new was happening.

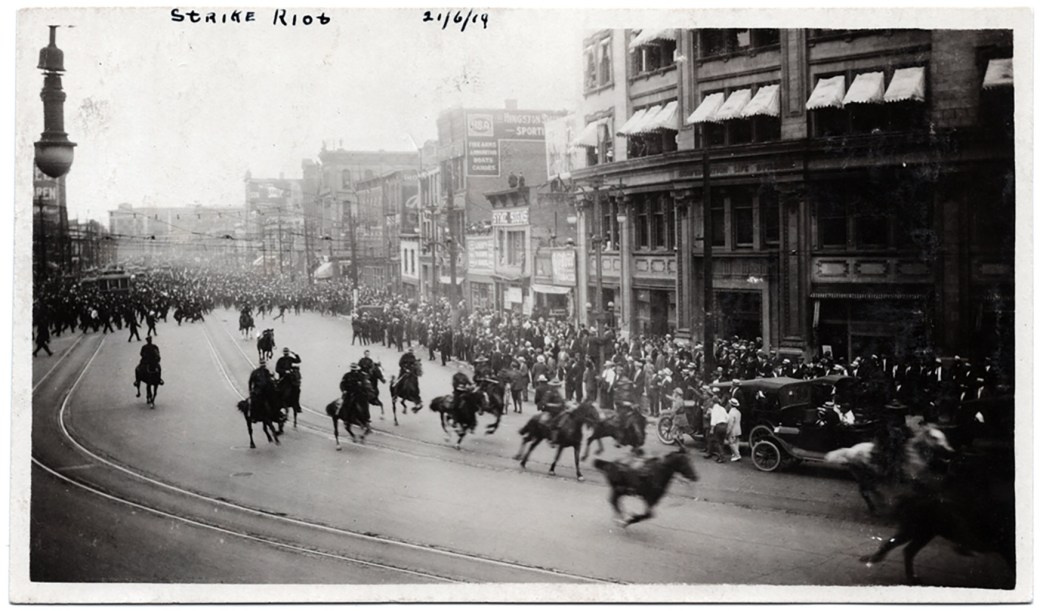

And on the day following the visit of the delegation, as I learned, the Great War Veterans returned. five or six thousand strong—and, it appeared, more “angry” than before. Outside the City Hall they found various citizens who in order to show their loyalty to the established order and their contempt for the so-called “Reds,” were sporting tiny British flags in their buttonholes. The soldiers tore these flags away.

“We fought for that flag!” they yelled, or so I was told. “We won’t see it used that way!’

The city fathers came out and tried to quiet them. The veterans howled them down.

“We want what we fought for!” they shouted. “Democracy!”

Their immediate demand was the withdrawal of the “ultimatum to the police.” When the strike first began, the police voted to join. The strikers asked them to remain on duty. They did so. Then the city government attempted to make them sign an agreement never to take part in sympathetic strikes, on pain of instant dismissal. They refused to sign it. This was the ultimatum to the police of which the soldiers were demanding the withdrawal.

“Do you think the ultimatum will be withdrawn?” I asked a husky young policeman at a street corner that night.

“Do I!” he responded. “Well, I guess it will! The soldiers will see to that.”

And they did. A few days afterward, it was announced in the press that “as the police are taking no part in the sympathetic strike, it has been decided to withdraw the ultimatum.” Also, “the soldiers who marched on the City Hall recently have decided to refrain from further demonstrations.”

All this, however, does not mean that the Great War Veterans Association has formally lined itself up on the workers’ side of the class struggle. As an organization, it has officially disclaimed any responsibility for the delegations to the City Hall. And the employers were not without hopes that as an organization it might be used in some way to hinder the strike. But as an organization, it is still “neutral.” Its individual members, however, are not neutral— and they have given the Winnipeg strike its specific color and significance.

I talked to innumerable soldiers in Winnipeg. I did not find one who was not hotly in favor of the strike. And every one of them assured me that all the soldiers held the same views.

Senator Robertson, Canada’s Minister of Labor, thought such a statement an exaggeration. “Why, one hundred returned soldiers have taken the place of the strikers in the Post Office,” he said. “That speaks for itself.”

I had not at that time heard the charge—unfounded, I believe—that the Board of Trade had secretly offered $25,000 to the first hundred soldiers who would take he place of the Post Office strikers. “When the soldiers heard of it they were so infuriated that some of them, after the demonstration at the City Hall, rushed on the Board of Trade Building, and were only prevented from wrecking it by the persuasions of their leaders.

In any case, a hundred out of ten thousand is not a large proportion. And the other nine thousand and nine hundred or so are enough to give the strike situation a new quality.

I understand that Mayor Ole Hanson of Seattle entertains a great contempt for the authorities at Winnipeg because of their supine attitude toward the strike. It would be interesting to know just how “Ole” would have dealt with these thousands of “angry” young men who know how to shoot and have ‘been public idols ever since their return from the war. If he had tried Seattle tactics in Winnipeg, his career might not be so widely admired.*

(*Mayor Hanson did not, as a matter of fact, use ‘Seattle tactics” in Seattle. His blustering was confined to public occasions; in private he pleaded with the Strike Committee. He did. not break the Seattle strike. The difference between him and the Manitoba officials is that they are candid.—EDITORIAL NOTE.)

Why are these soldiers so heart and soul with the strike? It must be remembered that the strike had its origin in a particular quarrel of “masters” and men over specific grievances in the iron-smelting industry; that it has spread by “sympathetic” strikes to other unions who have an interest, as unions, in the settlement, and that the discussion of immediate issues largely obscures the significance of the strike as an event in the class-war. The soldiers have been for a long time detached from these particular interests. It might, viewed superficially, not seem their cause. Why do they make it theirs?

The answer came from another soldier. He said to me: “The soldier is thinking hard these days. He reads of the large fortunes made during the war, and the honors showered on the profiteer, and compares it with his own hand-to-mouth existence. He is groping toward the light, and when he comes to a full realization of the causes, there will be, in the army vernacular, ‘something doing!”

So far, and in the mass, his interest in the strike is based on his deep resentment of profiteering. He feels himself against the men who made fortunes out of the war in which he fought and suffered and in which his comrades died.

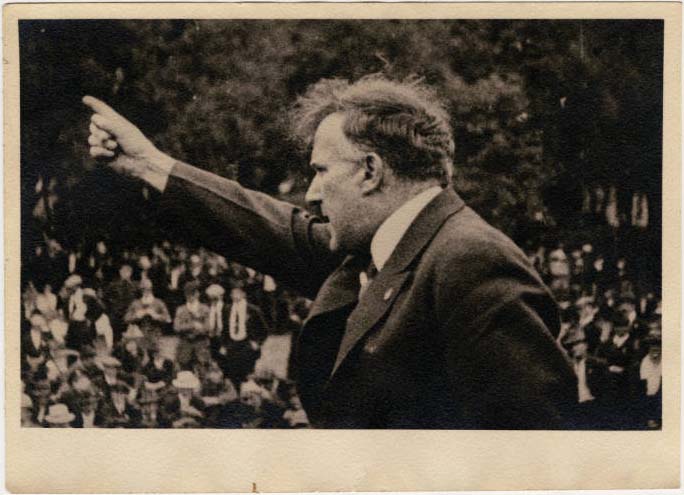

He is for any effort to take away some of those fortunes. He is for the unions as the immediate means of wreaking retributive justice upon the profiteers. A soldier said to me: “It would have been a revelation to any capitalist to have witnessed the enthusiasm aroused by the President of the Trades and Labor Council in his speech on the strike situation at

the general meeting of the Great War Veterans. And his ire is further aroused by his knowledge that the profiteers complacently expect to use him to crush the unions. The soldier whom I just quoted above told me of the “deep and growing resentment at the efforts of the (employers): Committee to use the soldier as the ‘goat’ in the labor struggle.”

The same bitterness at profiteering masquerading as patriotism, which made the soldiers tear the British flag from the lapels of the partisans of the employers at the City Hall, makes them feel that they and not the employers, represent—and are—Canada. Conversely, the employers are trying to make the strike appear the work of “aliens.” But a soldier said to one:

“We’re not going to be drawn into any fuss over aliens, you bet! ‘This isn’t an aliens’ strike—it’s a Canadians’. The alien strikers have been warned to keep out of sight as much as possible. We’re picketing the city and watching hard to see that no dirty tricks are started and fastened on aliens so as to get the soldier excited and make him forget the strike. The aliens know which side their bread’s buttered on, and they’re lying low. Anyhow, this talk about aliens is tommy-rot. The ‘Citizens’ aren’t saying a word about the aliens who’re scabbing—not a word! It’s only the ones who are loyal to the strike.”

How deep this soldier loyalty to the cause of the workers is, may be seen from the fact—too puzzling for the citizens committee to comprehend—that they do not seem to bother about the circumstance that one of the strike leaders is a Pacifist. The prejudice against Pacifists is strong in the army, and this particular Pacifist—the Rev. William Ivens—had openly declared that it was our duty to pray for the Germans! Nevertheless, the soldiers are for-him—he is in fact one of the leaders who has most influence with them. I asked some of them about it. They shuffled a little, and grunted—and then one of them spoke.

“Ivens may be a bit of a fool in some ways.” he growled. “But he’s straight. It’s better to pray for Germans than to steal from Canadians.”

That is the issue as the soldiers feel it—whether the thieves-—the profiteers who grew fat on war—shall have their way in Canada.

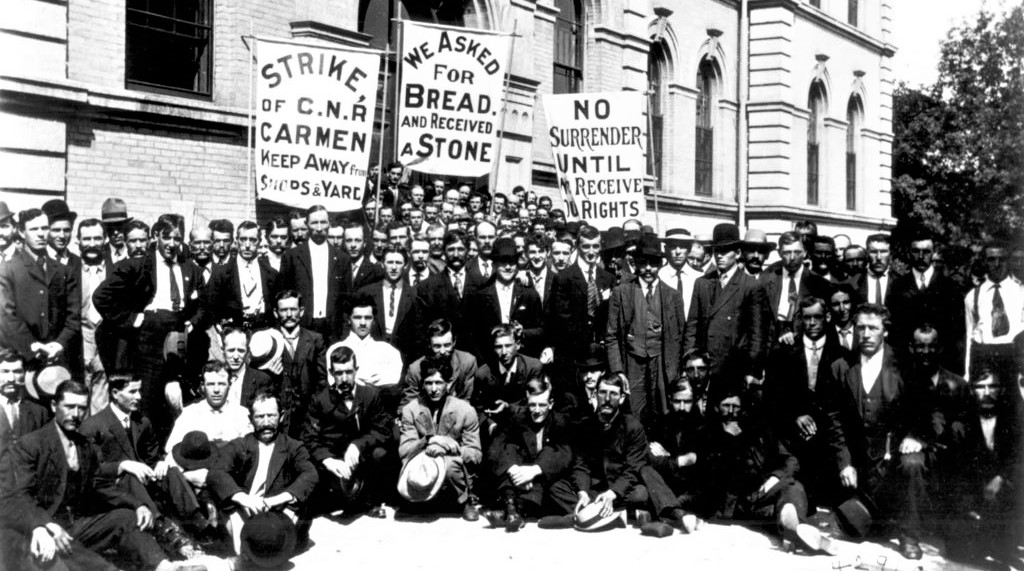

Technically, the strike situation is not quite so simple. The trouble began last April, when the Metal Trades Council presented certain schedules to the various metal trades employers. One of their demands was for a raise in wages. The cost of living, according to government statistics, has risen over 80 per cent. since 1914; wages in the metal trades have risen 18 per cent. in that period. The men asked for a 32 per cent. increase, akin to 50 per cent. increase altogether.

Another demand was for the eight-hour day; and the third was for recognition of the right to organize, which had been denied by the most powerful of the employers.

When this schedule was presented to the employers, they gave an answer to the third of these demands by ignoring the representatives of the Council, and calling into their separate offices committees of their own employees. To these committees the employers stated that they were willing to consider the question of a nine-hour day, but that they would not even discuss the eight-hour demand. When this was reported back to the Metal Trades Council, the men decided to strike May 1.

At the same time, the men in the Building Trades, who had gained recognition for their union the year before, were negotiating an increase in wages with the organization of their employers, the Building Exchange. The employers offered half of the increase asked, and the negotiations were prolonged through April, but a strike was finally called for May 2.

But this was only the top layer of the situation. Many of the employers told the men that their demands were fair, but that the banks refused to lend them money “if prices of business increase.” And this refusal was part of a campaign which was started throughout Canada as soon as the war ended to lower wages in order that Canadian manufacturers might be in a position to enter the commercial world-war with the manufacturers of other nations. In order to do this, it was necessary to break the power of the unions.

The Building Trades unions were in a particularly helpless case, for the reason that no building is imperative this year. So it was planned to beat their unions, one by one, and commence the grand smashing of all labor organizations in Winnipeg. Such is the situation as it was described to me by one of the strike leaders.

And it was to meet this situation that the Winnipeg Trades and Labor Council responded to the appeal of the metal trades and building trades workers, and passed on May 6, unanimously, a resolution pledging its support by “at once taking a vote to call a general strike.” The ballots went out the following day. Every organization was included—none was exempt. The voting ended on May 13, and on May 15, by the overwhelming mandate of the workers of Winnipeg: a general strike had begun.

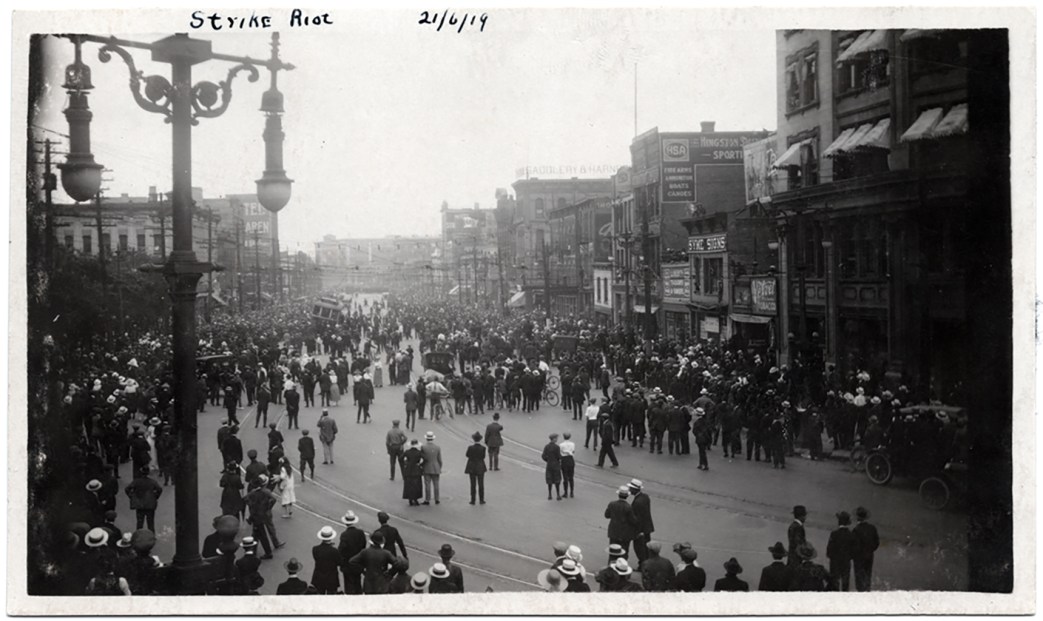

It was, of course, the most tremendous event in the labor history of the commonwealth. I attended a meeting at which the leaders of the Citizens Committee were endeavoring to dissuade certain delegates from the Trades and Labor Council of Moose Jaw from striking in sympathy with their Winnipeg Comrades. Much was made by these speakers of the “tyranny” with which the strikers had held the city in its iron grip. Men had not been able to procure food without showing a card reading “By order of the Strike Committee.” This was not told to the Moose Jaw delegation to impress them with the power of labor, but as an argument to show what an unnecessary “punishment” had been inflicted upon an entire city “because three employers had a disagreement with their employees.” And on that terrible first day of the strike, they did not fail to recite pitifully, “babies had cried for milk.”

I talked afterward with the Rev. Mr. Ivens on this subject. “Never,” he said “was a strike so carefully planned to eliminate unnecessary suffering or violence. We asked the police to stay in—we could not make them, but we asked them to. We asked enough electrical Workers to stay at the plants to keep the light going. We asked volunteers to run street-cars to take invalided. soldiers to and from hospitals. We asked water works employees to keep water at 30 pounds pressure—enough to supply homes of workers, but not enough for business.

“After the second day of the strike we felt that we had shown our strength. We wished first to prove what we could do, then to show how pure our intentions were, and how little we wanted to cause unnecessary suffering. We considered bread, milk, restaurants, absolute necessities, so we asked for volunteers to run them. We also let newspapers and theaters and movies re-open so that crowds might be kept off the streets. And in order that our volunteer workers might not be taken for scabs we issued the cards, ‘By Order of the Strike Committee.’”

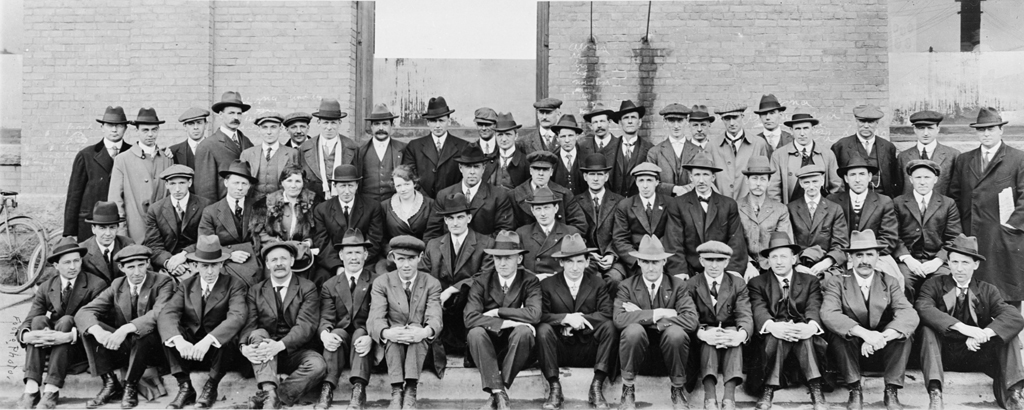

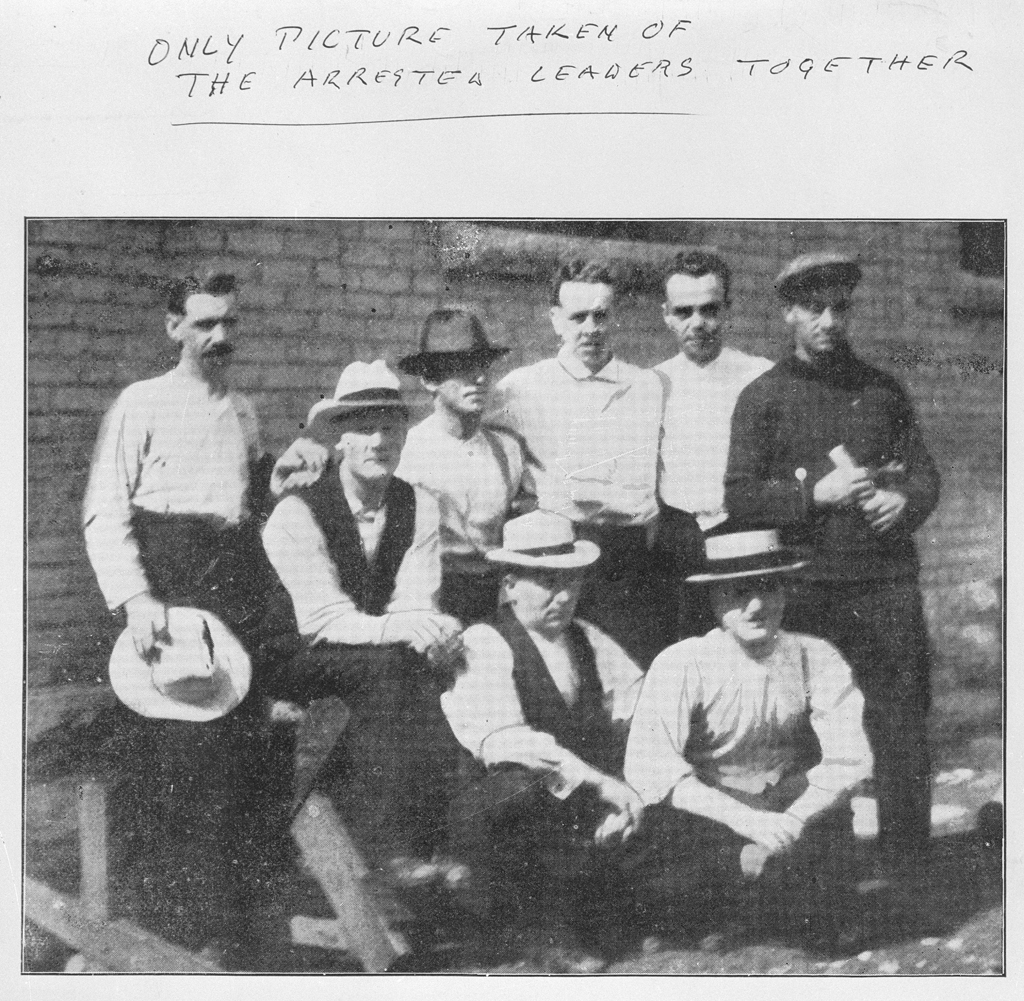

The strike was in charge of a committee popularly called the “Red Five,” appointed by the Trades and Labor Council. Three men from each union were afterwards added to this Strike Committee. The Labor News, of which the Rev. Mr. Ivens is editor, is their organ. Behind them stand the entire union membership of the city. And opposed to them are not only all the employers and financial interests directly or remotely concerned, but almost all the citizens of Winnipeg who do not belong to the “wagepaid” class. Thus, willy-nilly, it has become too palpably a class- struggle to suit those, on both sides, who would prefer to ignore or deny its revolutionary implications.

The Citizens Committee of One Thousand represents the organized attempt of the employers to obscure the class issue. Many and perhaps most of them are quite honest in doing so. They sincerely regard themselves as public-spirited men working to maintain law and order. They are, considered as a whole, eminently respectable and well-intentioned men who know nothing whatever of the realities of economics, and who fight for the existing system as loyally as any gentle Southerner for slavery.

They do not defend the Iron Masters; most of them disapprove the action of the Iron Masters in refusing to recognize the unions. Actually, however, they are the tools of the Iron Masters. Without their skillful and conscientious “scabbing,” the strike would be won in a week. The workers realize this, and detest the “C.C.” far more intensely than they do the Iron Masters who were the original cause of the trouble.

So far as the workers are concerned, the class struggle defines itself as a fight between Labor and Plutocracy, with Plutocracy faithfully supported ‘by the middle class—professional men, merchants, small manufacturers. Labor lumps them all together as “capitalists, scabs, liars and profiteers.” And the C.C., forgetting or not realizing that its function is to keep the class issue out of sight, retaliate with “Reds, Bolshevists, Socialists, tyrants and traitors.”

In fact, it is the Citizens Committee which most loudly advertises the leanings of the strikers toward Revolution. They refer to the cards issued by the Strike Committee to protect the strikers from being thought scabs when released for service on necessary work—the famous cards bearing the simple words, “By order of the Strike Committee—as proof that “a Soviet government has been established in the Labor Temple. It appears that the Manitoba government thought the same thing; at all events, the Premier offered to help bring about a settlement if the strikers would withdraw the cards!

Upon these representations, and at the urgent request of the troubled Mayor, the strikers did withdraw the cards. But, said one of the “Red Five” to me, “not one move was made by either Premier or Mayor to bring about a settlement. Evidently thinking we were weakening, they announced that before the question of collective bargaining could be discussed, the sympathetic strike must be called off, the policemen’s, firemen’s, postal workers’, telephone workers’ and all other civic workers’ unions must either leave, or sign agreements never to take part in sympathetic strikes, and to resign from the Trades and Labor Council. “To this demand organized labor has just one answer—Never! Realizing that neither civic, provincial nor federal governments are doing anything to bring about a settlement we are enlisting the aid of the entire labor movement throughout the country and trying to bring about a settlement through our economic forces. We have been very successful in this and we expect if our demands are not complied with that many more cities will join in the sympathetic strike. At present Calgary, Edmonton, Vancouver, a large part of Toronto and many smaller cities are calling general strikes to mark their disapproval of the situation.”

And I heard from the lips of one of the citizens, at the meeting before referred to, the grave charge that the strikers’ paper, the Labor News, had in spite of its disclaimer of revolutionary intentions, printed a chart showing the plan of the Russian Soviet system of government, with the caption: “Study this!” Also that a pamphlet, “The Bolsheviki, and the Soviets,” had been openly sold at an open-air strike meeting!

In short, if the Canadian strikers do not learn that this demonstration of their ability to run things themselves is the beginning of Revolution, it will not be the fault of the citizens!

But the struggle has not as yet been lifted to the level of full intellectual consciousness of its class character as yet. Take, for example, Mr. Thomas Deacon of the Vulcan Iron Works—one of the Three Iron Masters whose stubbornness toward the unions created the strike. There is doubtless no affectation in his inability to understand what is happening.

“I don’t understand the men at all,” he said to me.. “And I don’t understand the public who sympathize with them. Why, I’ve always paid fair wages, the best I could afford, and I’ve always treated the men well. It seems as if it was only necessary nowadays to buy a bit of land with one’s savings, build something on it that’s useful to the community and that gives employment to a lot of men, in order to be looked upon as the worst of scoundrels. The men can’t even pretend that I underpaid them. They want a ‘wage schedule’ by which the inefficient man will get as much as the efficient; they want an eight-hour day, although I’ve told them that I’m willing to give it if the Government makes it compulsory for all, but that if I give it now I’ll be ruined.

“What ails these men? Why, when I was a boy I worked hard—harder than any of them. I put myself through college on much less than they’re getting. I lived on less than nothing and saved every cent. No matter what position I took, my wages were raised— why? Why because I gave all my thought, all my attention to my work instead of to gadding. Why can’t these men do like me?”

Mr. Deacon does not even understand why there should be unions. “I never had to join unions,” he said. “I never had to ask anybody’s help. I bought a piece of land and started the Vulcan Iron Works with money which I had saved for years and with money which people I had worked for put in because they had faith in me. They say I won’t recognize collective bargaining. I say I did. I had committees where representatives of the men met with the heads and talked things over. I’ve no objection to collective bargaining, but I don’t want the kind where a Metal Trades Council or whatever they call it can walk in and run my business.

“Why, if I gave in to these men, I might as well shut up my shop!’

I could not but remember that other cry that rings down through history from another astonished and indignant monarch. “Why,” said Charles I., “should I grant these demands, I would be but the shadow of a king!”

But—although Mr. Deacon is supposed to be the chief stumbling-block to a settlement—the men prefer him to their other opponents; they say, “He is honest.”

Mr. Deacon doubtless is not really aware that he is a protagonist of Capital in a class war. He merely acts—habitually and forcibly and unmistakably—in that capacity. And by so doing he serves to clarify the situation in the minds of the workers.

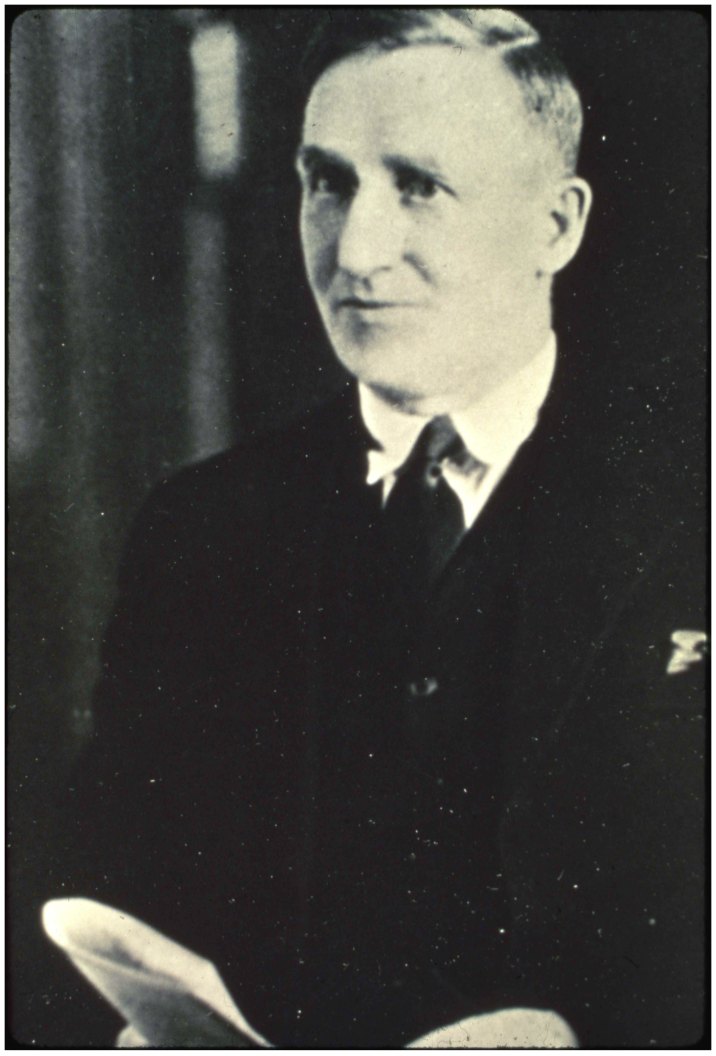

The position of the Manitoba Minister of Labor, Senator Robertson, is more difficult. He is supposed to occupy a neutral position, and as such should be concerned in finding grounds for a “settlement” of the difficulties. But since such a settlement would necessarily include everything that the strikers have very modestly demanded, and thus come into deadly conflict with the plans of the employing class for reducing labor to a state of complete subservience, he is compelled to find reasons for opposing the strikers’ program. Since there is no such reason furnished by their actual program, he is compelled to look beneath this program and find in its spirit and potential results the beginnings of a Proletarian Revolution. Thus he wired to the Mayor of Calgary:

“I have no hesitation in saying that this strike is not for the purposes alleged, but is on the contrary an attempt of certain radical forces in the community to seize control of the Government.”

I asked him just what he meant. His reply was specific. “It is,” he said, “an insidious attempt to ‘force the One Big Union—which is nothing more or less than the Russian Soviet system on Canada.”

I asked him what—aside from its identity with the Soviet system—was the matter with the idea of One Big Union?

“I will tell you my objection to the O.B.U.,” he said. “It is an attempt to upset the crafts unions.”

And what then? I asked.

“It would serve to break up the power of the crafts unions, and then, when it didn’t work, there would be nothing left but the Social Revolution—or so they say.

“Now understand me,” he added. “I am a union man. I stand for the unions. I am and always have been a Labor man. If this attempt on the part of the – strikers were a forward movement—a movement which made for good—I should be the first to approve it.

“But its aims are different from those of crafts unionism. The strike, for instance, must be rightly used. In this instance it has been abused. The various unions have broken their agreements with their employers, in order to join in the sympathetic strike. Tactics of this sort do not commend themselves to I honest men.

“In this strike three employers—three iron masters—are to blame. Let us allow, for the sake of the argument, that they are to blame. Very good; why then should the whole community be made to suffer? During the first few days, children could not get milk in some instances and were brought near to death.”

I thought of how in Montreal, my home, 50,000 babies have died in the past thirteen years, of whom nearly all might have been saved had the conditions for which these men in Winnipeg were now striving been attained. But we continued the discussion.

“They refused,” went on Senator Robertson, “to submit to arbitration. Twenty-four hours before the general strike was called, the provincial and civic governments approached them begging them to submit their differences to a Conciliation Board. They refused.”

I was aware that five months before the general strike was called, Labor had asked the Provincial Government of Manitoba to pass a law identical with the British Industrial Act, making collective bargaining compulsory; and that the Government had offered them instead an Industrial Disputes Act in which the clause about ‘recognition of unions’ was deleted—a crippled measure which Labor indignantly refused to accept. I mentioned this to Senator Robertson.

He said there might be many good reasons for not “copying the British Act slavishly.”

And no doubt there were. There is little doubt also that Senator Robertson knows the exact nature of these reasons. I went away impressed with the official sanctity of the crafts union system, as a means of keeping the workers apart; and with the vast revolutionary significance, never confessed to me by the strikers themselves, of their actions.

I went to see the Rev. Mr. Ivens. He is a man of terse, clear-cut speech, and his personality is founded upon the quiet integrity which everyone cannot but admire. He began with a statement.

“Please make this clear. I am of British birth. I am a graduate of the University of Manitoba. I worked my way through the university. I am a minister of the Methodist church. I left my parish not because I was turned out of it—the majority wanted me to stay—but because I wanted to form a Labor church. Another parish was offered when I left mine, but I refused it. I did not better my position financially when I undertook the editorship of the Labor News.

“I am an internationalist and a pacifist. ways been against war of any kind. I am against revolution because it involves war. During the European War I neither tried to restrain anyone who wanted to go to fight nor urged anyone to go. I have two brothers in the British army. The older rose from the ranks, was made major in command of a Heavy Battery, and may get a decoration. The younger is a sergeant who has refused promotion and who has won five medals. He has been about fourteen years in the army—fought in the Boer War. I mention these facts to show the absurdity of the statement that I am a Russian in disguise.”

“Then it is not true,” I asked, “that you and your associates are, directly or indirectly, fomenting revolution?”

“We are doing everything in our power to avoid it. Personally I believe always in evolution. I believe that what brains cannot accomplish bullets cannot.”

“You are not then attempting to establish a Bolshevik Party in Canada?”

“No. Absolutely not. Four out of five of the so-called ‘Red Five’ are always in trouble with the real ‘Reds’ because they want everything done constitutionally that can be done.”

“Senator Robertson says that the O.B.U.”—I repeated the Senator’s arguments.

“Crafts Unions, of which the Trades and Labor Council is composed,” he said, “were the first step. They did an excellent work. The Industrial Union is the next logical step. That is all.

“This is a strike for a living wage and recognition of unions.

“But our enemies are right in asserting that there was more behind the strike. There was. After the war ended, the Board of Trade sent out a circular letter to merchants, editors, public speakers, commending their opposition to Bolshevism and asking them to keep it up. The Canadian Manufacturers started a campaign to lower wages so that they might be able to compete successfully with the manufacturers of other nations. Three demands were made:

“(1) Greater production.

“(2) Thrift (among workers, of course).

“(3) Increased population through immigration (and this in spite of the ever-increasing army of the unemployed).

“Now with all this in plain view, we realized that there was a definite campaign afoot to lower wages and to break the power of the unions. Note the answer of the employers to the men—’Demands reasonable, but wages must be lowered.’ Practically they said, “The financiers won’t let us give you a living wage.”

“We saw that we had to fight them. The Trades and Labor Council was practically unanimous—the fight must be made. Now they talk of me as a dictator—but I had no power but what was given me. I had not even a vote with the Trades and Labor Council. The vote was the most spontaneous I ever saw. They appointed five men as the nucleus of the Strike Committee. First two men, then three, from every union were added.” He went on to give me the details I have already stated as to the conduct of the strike.

“And all the men want is the right of ‘collective bargaining’ in behalf of a living wage for themselves?” It seemed a quiet, reasonable thing, after all I had heard about Revolution from the Citizens and. the Government. Only, I remembered that it seemed neither quiet nor reasonable to Mr. Deacon of the Vulcan Iron Works.

“Collective bargaining,” said Mr. Ivens, settled by the Iron Masters. Only Dominion legislation can settle it. If the Citizens’ Committee are sincere in saying that they are not the tools of the capitalists let them petition Ottawa for legislation in favor of collective bargaining. So long as they don’t do this, and so long as they do scab they prove that, whatever they may state to the contrary, they are our enemies.

“The Civic, Provincial, and Federal Governments have presented ultimatums to civic employees in every branch, demanding that they sign an agreement not to engage again in a sympathetic strike. This makes the issue national. If we allow this ultimatum to pass, Labor is thrown back twenty-five years at least. We can’t allow that, of course; therefore it is now a fight to a finish. Either these employees must be reinstated on their own terms or sympathetic strikes will take place all over Canada and all industries will be upset. Win we must. And will!”

From those mild premises of a moment ago, the argument of the pacific Rev. Mr. Ivens had seemed to lead very swiftly—and inevitably—back to open class-war.

“But can you win?” I asked.

“Yes.”

“If the strike is prolonged will your money hold out?” —

“Not indefinitely—but I think the strike will be settled first.”

“But if it is not?”

He hesitated slightly.

“It will be settled. The soldier has no intention of starving or of seeing us starve. He has great power.”

“Then the soldier,” I said, “is the key to our economic puzzle?”

Mr. Ivens frowned as if thinking.

“I wouldn’t put it in just that way. Say, rather, that the Soldier is the great Titan who will carry Labor safely into the Promised Land!”

The Liberator was published monthly from 1918, first established by Max Eastman and his sister Crystal Eastman continuing The Masses which was shut down by the US Government during World War One. Like The Masses, The Liberator contained some of the best radical journalism of its, or any, day. It combined political coverage with the arts, culture, and a commitment to revolutionary politics ay a pivotal time in Left history. The writings by John Reed from and about the Russian Revolution were hugely influential in popularizing and explaining that events to U.S. workers and activists. Increasingly, The Liberator oriented to the Communist movement and by late 1922 was a de facto publication of the Party and was sold to the Party by Eastman. In 1924, The Liberator merged with Labor Herald and Soviet Russia Pictorial into Workers Monthly. The Liberator is an essential magazine of the US left.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/culture/pubs/liberator/1919/07/v2n07-w17-jul-1919-liberator.pdf