An excellent overview of the state of ‘the auto industry and its workers’ on the eve of the Great Depression by Robert W. Dunn’s Labor Research Association.

‘The Auto Industry and Its Workers’ by the Labor Research Association from Labor Age. Vol. 18 No. 4. April, 1929.

Desperate Need For Unionization

THE automobile industry has grown from infancy to maturity in the last 30 years. At the beginning of the century, inventors were playing around with “horseless buggies.” Today more than 30,000,000 cars roll over the dirt and macadam roads of the world; 9 out of every 10 of them were “made in America.” In volume and turnover of business the automobile industry outranks every other in this country.

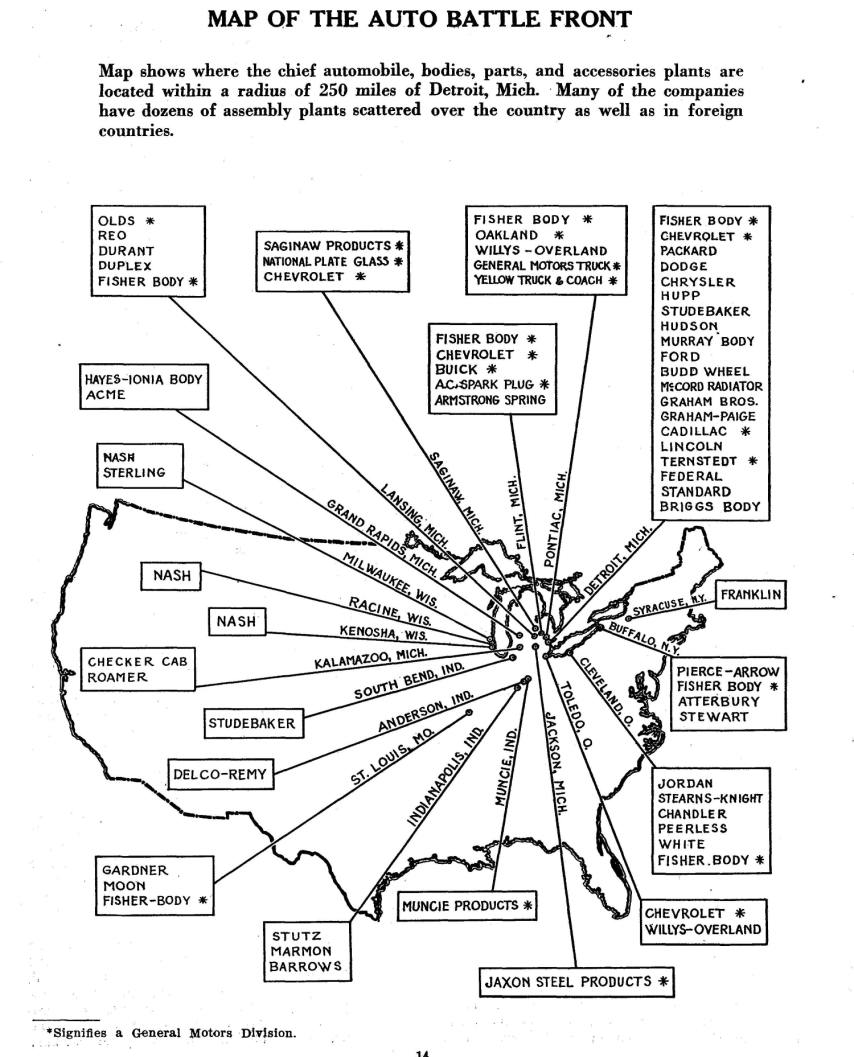

In some 1,400 plants manufacturing motor cars, trucks, bodies, parts, and accessories about 425,000 workers are employed. About 1,200 of the 1,400 are bodies, parts and accessories plants; the other establishments make or assemble completed cars. The few large plants making finished motor vehicles — Ford, General Motors, Hudson, Packard, Chrysler, Hupp and the rest — are all located within a radius of about 250 miles from Detroit, the center of this world industry.

Mountains of Profits

The profits of the motor companies have been almost unbelievable. Previously the U. S. Steel Corp. set world records in the, amount of profits extracted from the toil of the workers. Now it is General Motors which, in the first nine months of 1928, showed net profits of over 240 millions, more than the company had made in a full year before. As a result of this the company issued another stock dividend which was the largest bonus ever handed out to the stockholders of any corporation in history. Net profits of General Motors for 1928 were $276,500,000, an in[ crease of 18 per cent over 1927. Both in 1926, 1927 and 1928 the automobile companies were the leading profit-making stocks in America with the exception of railroads. In fact, in 1927 these companies made five times the average profits of iron and steel companies. Even on the pyramids of capitalization, built up by one stock dividend after another, a group of these companies were able to pay over 28 per cent on total capital in 1927. Actually, however, their profits on their original investments ran at an annual I rate of anywhere from 50 to several thousand per cent!

In the early days these amazing profits poured into h the pockets of the original owners, but gradually the bankers have taken control of the industry, encouraging mergers and consolidations that will divert more of this golden stream into their coffers. The Dillon Read deal with Dodge Brothers and its final consolidation into Chrysler Motors is an example. The control of General Motors is in the hands of J. P. Morgan & Co. and the Dupont chemical interests. Only Ford has thus far been able to avoid control by the bankers, and even he is now beginning to sell the stock of his foreign companies to foreign and native bankers.

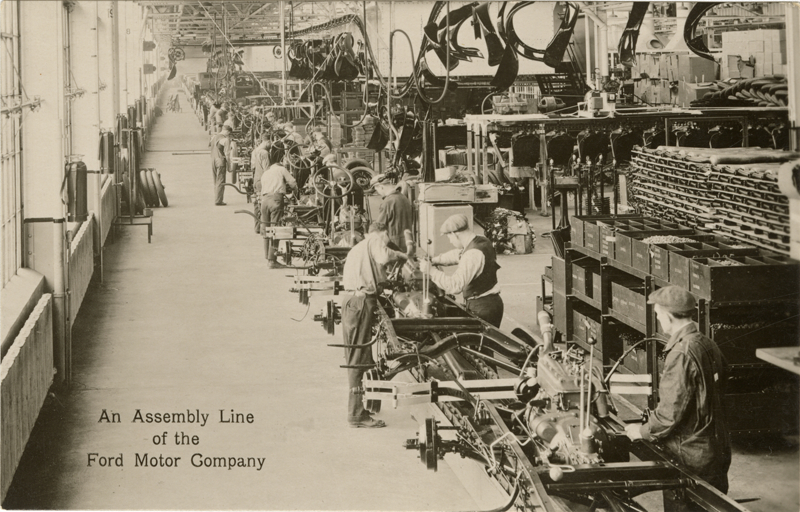

The auto plants are the most highly mechanized in this country. Largely because of this the productivity of the workers has risen faster than that of workers in any other industry. Their tasks are minutely subdivided and highly specialized.

Few Skilled

In a typical plant the force may be divided into (1) the tenders and assemblers who watch machines and perform a given operation as material flows by them on the “belt”; (2) the technical men who design, plan and cost the work; and (3) the clerks, inspectors and foremen who record what is done, and check and watch the others. About 40 per cent of the workers in the typical plant are tenders and 15 per cent assemblers. Not more than from 5 to 10 per cent are the traditionally skilled workers. The rest are inspectors, bosses and “common” laborers not at the machines. The tendency has been for the assemblers and tenders to increase in number while skilled workers and common laborers disappear. So that today probably 80 to 90 per cent of the force are the unskilled who can learn their jobs in a few hours, or days.

Because of the lack of skill required the motor companies make a practice of hiring younger men. They need workers in their prime. Those reaching the age of 40 or 45 are considered “old.” They are rejected by most companies, and are frequently discharged and their shoes filled by younger feet that can keep up with the pace. Young women have also been employed in increasing numbers, particularly in the Hudson plants, in the Briggs (body) plants, and in all plants making accessories and parts such as A. C. Spark Plug and Continental Motors. In 1925 over 5 per cent of the automobile workers in Michigan were women and girls.

Speed ’em Up!

One of the primary complaints of all these workers is the speed-up system. It grows out of the demand for lower labor costs, the increasingly keen competition between the companies, the introduction of new models, seasonal rushes, the installment of new machinery, and other factors that accompany the rationalization of the industry. Speed-up shows itself in a variety of ways — by moving the line faster, compelling workers to “step along” with it ; by reducing the number of workers while compelling the remainder to turn out the same amount of work; by various schemes of wage payment calculated to make workers put their last ounce of energy into their tasks ; by various group “incentive” systems such as the gang bonus; by high threats of discharge and the overwhelming: fear of the worker that if he does not “get a move on” he will find himself on the street with one of the job hungry unemployed in his place The average hours of labor in the plants are between 50 and 51 hours a week; but overtime, which makes a workday or 11, 12 or 13 hours, is the rule in most plants in the season when the production lines must be rushed. There is a marked seasonal trend production usually being high during the late winter and spring months and lower in the summer and again toward the close of the year. But with companies now bringing out their cars at more irregular intervals the demand for labor power is even more fluctuating than before. When plants change from one model to another they may close down for from three weeks to several months and frequently a different set of workers will be taken on for a new job.

The U. S. Bureau of Labor Statistics finds that “the automobile industry shows the greatest instability of employment of any of the industries so far analyzed by the bureau…Not only does the industry as a whole make a very bad showing, but irregularity and uncertainty of employment conditions are the rule among practically all the establishments covered.”

“High Wages”

This irregularity of employment is, of course, reflected in the earnings of auto workers. It is true that their wages, in the main, are higher than those in other unorganized industries such as cotton, textiles or meat packing. Taking annual earnings for fulltime employment we find that they were not more than $1,600 in 1927, as compared with about $1,300 for manufacturing as a whole. But in view of the unemployment during that year this figure overstates the actual earnings of the average worker who certainly did not put in full-time.

Real wages of auto workers have, in fact, shown very slight gains during the life of the industry. From an index base of 100 in 1899 they went up to 112.1 in 1925 and then back to 108.6 in 1927. And, if we take into account part-time employment, real wages for all the workers attached to the industry were 17 per cent higher in 1926 than they were in 1919. However, in 1927, partly because of the great Ford lay-off, they were actually 6 per cent lower than they were in 19 19, according to computations made by William E. Chalmers of the University of Wisconsin who has worked in auto plants for three successive years and who has made a close study of auto wages.

But even if we take the money wage in full time employment as it stood in 1925, we find that it was at least $350 below the amount required to maintain what the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics has termed the “minimum health and decency budget” as priced for the City of Detroit. In other words, automobile workers are not “well paid.” They do not receive “high wages.” And they are receiving far below workers in organized trades. It is only in comparison to the low wage standards of other non-union industries, with much lower rates of productivity, that the auto workers standards seem to be little better than the others.

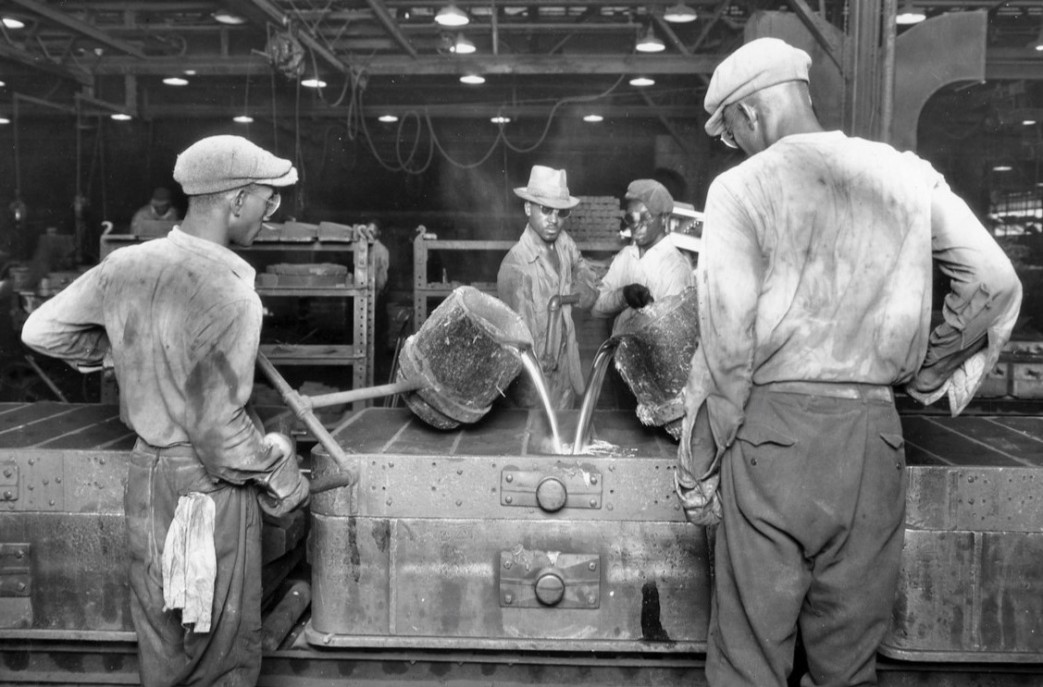

Health and safety conditions among auto workers are also contrary to the flights of fancy indulged in by press agents for the corporations and business magazine interviewers who talk of “wonderful conditions” of work. Ask the man who does his 50 hours or more a week in one of these plants, or his 40 in Ford’s. The accident rate is high for the workers and the accident severity is even higher, and had been going up steadily in recent years, faster even than the phenomenal increase in the rate of production. The massing of huge machines, the crowding of moving conveyors and chains, the tremendous speed of operation, the mad driving of the bosses to achieve production records, combined with the long hours and overtime work in certain plants, has shot up the accident severity rate.

Poison Fumes

The dangers to health are even more outstanding, especially in departments finishing auto bodies. Lead, wood alcohol and benzol are the most poisonous substances injuring the painter who uses the spray gun. Anemia, respiratory diseases, hemorrhages and nose and throat infections are common diseases among the painters. The new chromium compounds, used in making non-tarnishing headlights and parts, are very dangerous and have caused poisoning and skin ulcers. There are also many fumes, vapors, and dusts, injurious to the health. Added to this go the absence of decent washing facilities in many of the plants, the fatigue and strain of the speed-up, and the fact that only 15 minutes, as at Ford’s, is allowed in which to bolt a hurried lunch. All these factors contribute to a high sickness rate among the workers and a gradual undermining of their health.

These conditions are not going to be improved in the future. The curve of workers’ conditions is definitely downward. For the outlook in the industry is about as follows:

Competition, especially in the field of lower priced cars, is becoming more strenuous between a few giants. Ford, General Motors, and Chrysler promise to turn out about 80 per cent of all the cars during the next few years. Their advertising campaigns in the current press indicate the intensity of the competition to get the lion’s share of these sales. To meet the pace set by these powerful groups more mergers and consolidations are bound to precipitate.

Production is pegged at a little over 4 million cars a year. Replacements call for possibly 2 million. “New buyers” are steadily decreasing in number. “Two-car families” are decidedly limited. New layers of demand are not in sight in this country. Contrary to the general belief domestic sales of cars did not establish a new high record in 1928; they merely approximated the high 1926 total.

Expansion Abroad

So export markets are being feverishly pushed. Export of cars from U. S. and Canadian plants (All Canadian auto establishments are branches of U. S. firms) absorbed more than 14 per cent of production in 1928; and there are more than 30 American assembly and manufacturing plants abroad. But the European capitalists have their own plants, and are vigorously resisting American encroachments. And even should American companies buy up foreign plants, as General Motors has just absorbed the great Opel Works, it would not mean more cars made in America for export. It would only mean that German workers, now exploited by the same corporation, will have firmer grounds for solidarity with Michigan motor workers.

Irrespective of the moderate gains that may be expected in the export market, instability of employment and unemployment are likely to increase in the plants. At present the “practical capacity” of these plants is nearly 8 million cars a year, and production predictions by the various companies at the beginning of 1929 actually approached this fantastic figure. But, as we have indicated, the home and foreign markets together call for something over 4 million a year, and no more. This leaves a practical capacity for at least 3 million cars unused. The ups and downs of employment will continue to be a characteristic of the industry.

The boom days are clearly passing. “Stabilization” and “maturity” are the two words most frequently applied to the industry, even though the producers shout that the saturation point has not been reached. Regardless of which group of capitalists wins in the fierce trade war now in progress, the auto workers will face more frequent and more severe wage cuts, long hours and more speeding up. Organization will be desperately needed to fight the employers’ associations, to defend such working “standards” as the workers have at present, and to struggle for better ones.

*The above material on the condition of the industry and its workers was prepared by the Labor Research Association whose Executive Secretary, Robert W. Dunn, has just completed a special study published under the title, “Labor and Automobiles.”

Labor Age was a left-labor monthly magazine with origins in Socialist Review, journal of the Intercollegiate Socialist Society. Published by the Labor Publication Society from 1921-1933 aligned with the League for Industrial Democracy of left-wing trade unionists across industries. During 1929-33 the magazine was affiliated with the Conference for Progressive Labor Action (CPLA) led by A. J. Muste. James Maurer, Harry W. Laidler, and Louis Budenz were also writers. The orientation of the magazine was industrial unionism, planning, nationalization, and was illustrated with photos and cartoons. With its stress on worker education, social unionism and rank and file activism, it is one of the essential journals of the radical US labor socialist movement of its time.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/laborage/v28n04-Apr-1929-Labor%20Age.pdf