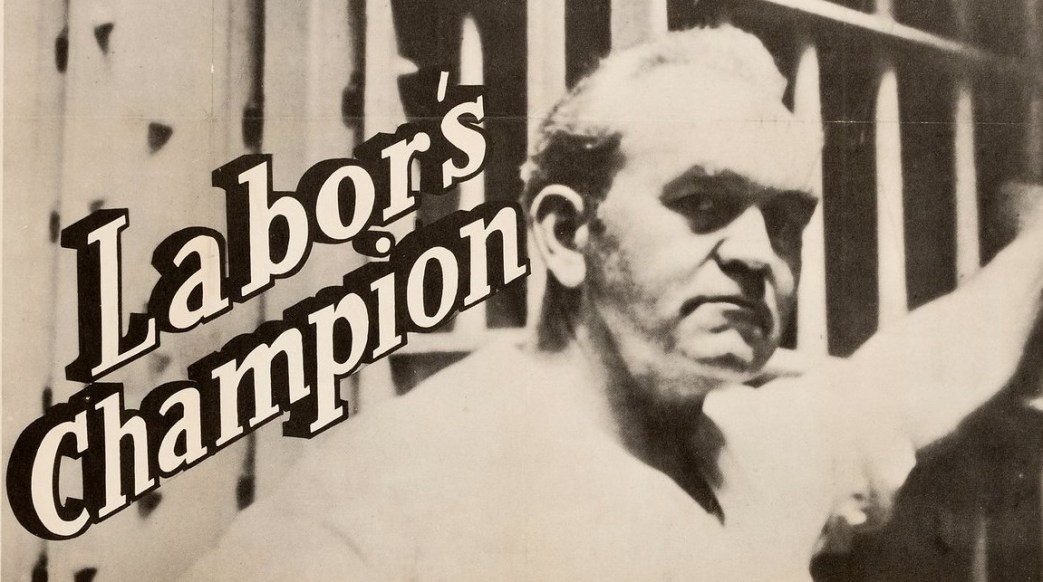

Railroaded for the 1916 Preparedness Day bombing in San Francisco, militant worker Tom Mooney became one of the most celebrated political prisoners of the 20th century. Here is a valuable short look at his early life.

‘Tom Mooney, Son of the Workers’ by Arthur Ames from Labor Defender. Vol. 9 No. 5. May, 1933.

All through his early life poverty was Tom Mooney’s daily companion.

He was born a coal miner’s son. The family lived in a small Indiana mining town, in one of those tumble-down, weather-beaten company shacks that spot the coal fields of America. There were days in this shack, Tom Mooney recalls, when food was scarce. Sometimes he went to bed hungry.

His father, a militant worker, helped organize the local Knights of Labor among his companions of the pit. A strike was called, thugs were sent in, then- as in coal battles now- terror reigned.

One day, in self-defense, Tom Mooney’s father shot a company-killer down. Thinking he had slain his assailant, he rushed home. In the dead of night the family packed up, and carrying what they could on their backs, fled the town on foot. Shortly afterward, the father died, a victim of tuberculosis: “the miner’s sickness.” Tom’s mother had to sell his drills and picks to cover the burial expense. Now the burden of the family fell upon Mother Mary Mooney. She moved to Mt. Holyoke, Mass., worked twelve hours a day in a paper mill, skimped and slaved. Often there was no money for shoes, no money for rent and bread. At night, after the grueling day in the mill, Mary Mooney took in washing for the neighbors.

Tom and his brother John helped as best they could. They did odd jobs, ran errands, sold papers, picked up coal from the railroad track. All in all Tom got four years of schooling. At 12 he was working in a paper mill, earning $2 a week to help the family out.

One day a foreman in a foundry who brought his laundry for Mother Mooney to do, offered Tom a job. After serving his four year apprenticeship, he joined the International Core Makers Union, and has remained a member in good standing till this day.

Fired because he had insisted that the women in the foundry be paid as much as the men, Tom Mooney began travelling around Massachusetts, holding jobs, organizing, being blacklisted, getting fired. His militant union activities kept him on the move.

Then, with his brother and his sister holding good jobs, Tom Mooney decided on a trip to Europe to escape for a time the drudgery of foundry work. He wanted leisure, some knowledge of the culture of the old world, a little gayety and life. He wandered about the large atlas of the continent, sat in cafes, went to theatres, art galleries, boulevards. While strolling through a gallery in Rotterdam, he encountered an American of a different type than any Tom had known. Nicholas Klein, delegate to the International Socialist Congress at Stuttgart, was a radical intellectual, with a vast background of reading and study, with a knowledge of history and world movements. The intellectual and the sturdy young worker spent hours talking together. For the first time, Tom Mooney got some glimpse of the historic mission of the working class.

He abandoned the art galleries, and travelling through Germany, France, Belgium, and Italy, he sought out everywhere the dwelling quarters of the workers, noting how in all countries alike they lived on the ragged edge of hunger, overworked, without rights, beaten down by the greedy few who owned the tools and amassed the wealth of the land. Now Tom Mooney had become a class-conscious worker.

Returning to America in the crisis year of 1908, he found jobs hard to get. He drifted, worked with the oppressed Negro dockwallopers on the wharves of New Orleans, spent some time in Vera Cruz and saw the exploitation of the peons, wound up in Stockton, California, and found a job.

Here he joined the Socialist Party and soon became one of the most active and beloved workers on the Pacific Coast. He distributed literature, collected subs, agitated, held meetings; and when, one day, the famous “Red Special” pulled into town with Debs aboard, he made so dynamic an impression, that Debs took him along on his tour across the continent.

The election tour over, Mooney attempted to matriculate in the University of Chicago, but was rejected because he failed to have sufficient “credits.” He set about grimly to educate himself. Armed with an outline of reading prepared for him by A.M. Simons, the socialist and historian, Mooney sat pouring through volumes in the Marshall Field research library until his “course” was completed.

With an old motorcycle he next toured the west, collecting subs in a national campaign for Wilshire’s Magazine, a socialist review, and all but won the first prize, a trip around the world. He was given, instead, a special prize: passage to the International Socialist Congress in Copenhagen./

In 1910 Mooney returned to California. He knew his mind now. He had found himself. He knew his life was inextricably bound up with the fate of the working class. He believed in the workers, believed in their ultimate triumph, their emergence into power as he saw, East and West, alike along the Mississippi, the Rhine, and the Po, a dying class attempting desperately to keep its strangle-hold on the masses it exploits. How he was framed because of his belief in the working class and his organizing them for the struggle to gain power, that story every worker now knows. His faith in their triumph he still maintains, after 17 years of imprisonment, as he peels onions and potatoes in the dungeon to which capitalism condemns “dangerous” workers.

As one of its first steps toward achieving that power in America, the working class must free Tom Mooney. Realizing this, without any selfish motive, Mooney calls on the working class to build the Free Tom Mooney Congress in Chicago, April 30 to May 2, and to demand the new trial April 26 which will deal a smashing blow to the frame-up system.

Labor Defender was published monthly from 1926 until 1937 by the International Labor Defense (ILD), a Workers Party of America, and later Communist Party-led, non-partisan defense organization founded by James Cannon and William Haywood while in Moscow, 1925 to support prisoners of the class war, victims of racism and imperialism, and the struggle against fascism. It included, poetry, letters from prisoners, and was heavily illustrated with photos, images, and cartoons. Labor Defender was the central organ of the Scottsboro and Sacco and Vanzetti defense campaigns. Editors included T. J. O’ Flaherty, Max Shactman, Karl Reeve, J. Louis Engdahl, William L. Patterson, Sasha Small, and Sender Garlin.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/labordefender/1933/v09n05-may-1933-lab-def.pdf

I’m so grateful for this and other articles about Tom Mooney on this site. This one in particular provided some details I appreciate and didn’t know. He was my grandfather’s first cousin, I am down the rabbit hole to find all I can about him. If by any chance someone reading this is a relative, please contact me: artismooney@gmail.com.

LikeLike