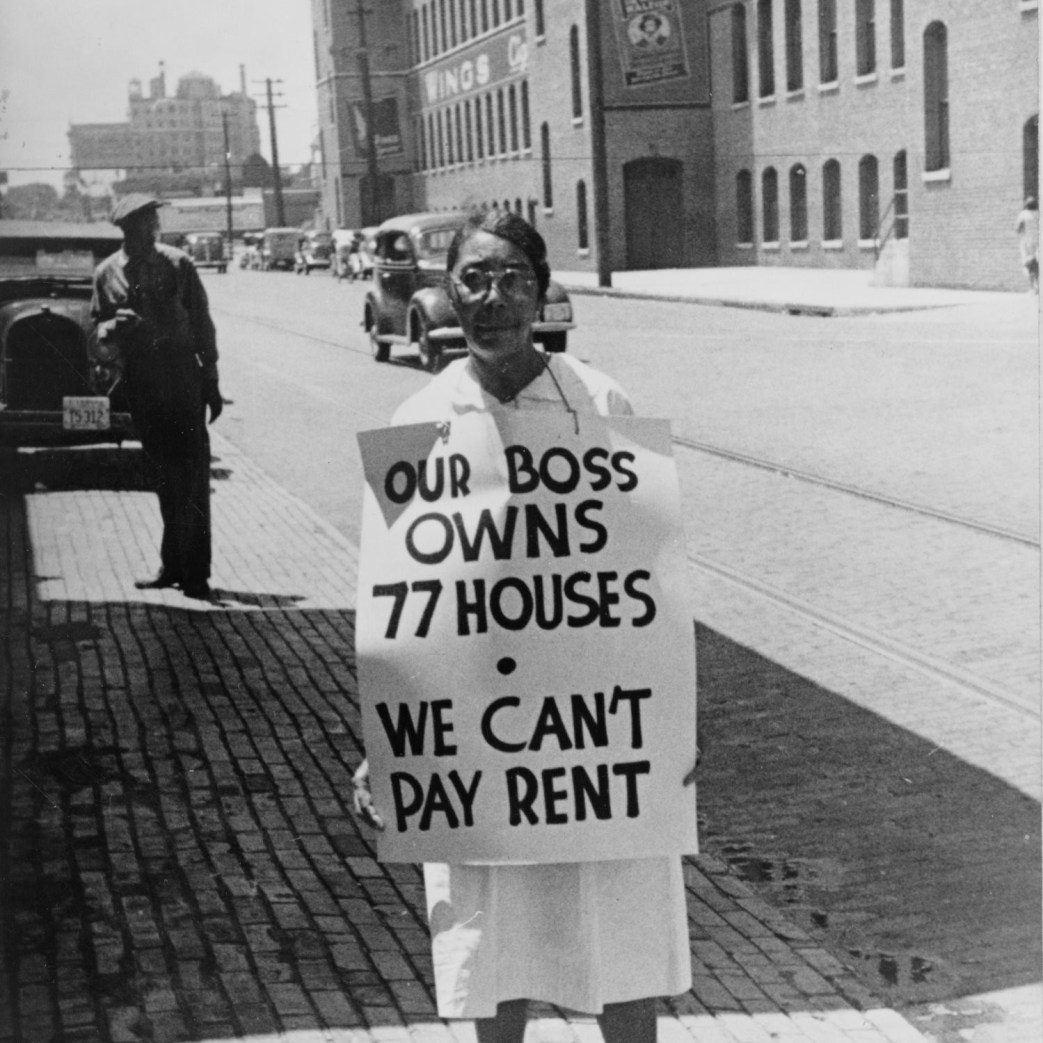

We may not now have the the Great Depression, but we do have a housing crisis. Here, a look at conditions in the early 30s, the parasitic role of the market, and the failed proposals to solve them; with much that is familiar today.

‘Mansions in the Sky’ by David Ramsey from New Masses. Vol. 10 No. 5. January 30, 1934.

ONE of the latest aspects of the Roosevelt scheme to solve the crisis and unemployment scheme is housing. Under the supervision of the Division of Housing of the Public Works Administration low-cost housing and slum clearance are to serve the double purpose of reviving the defunct building industry and launching a new business boomlet.

The housing problem has grown very acute during the crisis. A recent survey in Philadelphia indicated that while there were approximately 25,000 vacancies, 29,000 families had been forced to double up because of reduction in income. The Bureau of Labor Statistics has found that the number of new dwelling units provided for each 10,000 of population was 121.8 in 1925, averaged 92.5 from 1921-1930, but was 21.4 in 1931 and 5.9 in 1932. In New York

75 percent of all multiple dwellings in Manhattan were slum tenements built before 1900.

It is such conditions that the Roosevelt regime proposes to eradicate. A tremendous wave of ballyhoo has been set into motion, especially in New York. Fat, dumpy social workers who are just “thrilled” at the beauty of the plans, Pathe News, speakers’ bureaus, and landlords have been mobilized into what Langdon W. Post, Tenement House Commissioner of New York calls “a fighting force for better housing.” As is typical of all parts of the recovery program, a fight has developed between the bankers and the landlords who will profit from slum clearance, and other capitalists who would like the money to be diverted to other capital goods industries. On January 8, the United Press printed a story that the “use of Federal funds for slum clearance and housing projects in general has been abandoned as a major part of the Roosevelt recovery program.” Although the U.P. claimed to be “authoritatively informed,” Secretary of Interior Ickes denied this in the New York Sun of the same day. To date there has been no confirmation of the U.P. story, and it appears that housing will continue to be pushed.

Behind the housing ballyhoo is the recent trend of direct subsidies and loans by the government to railroads and industry. Neither decent housing for slum dwellers nor jobs for the 2 million unemployed building workers will be achieved. Technological advance and the purpose of the proposed plans eliminate the possibility that any except a small portion of the unemployed will get jobs. Events of the past few months also disprove Administrator Ickes’ promise that the government would not depend “upon private enterprises or limited dividends corporations” to initiate the housing program. All projects to date are of just this nature, that is, are profit-making ventures. A casual survey of the projects shows that they are really designed to give subsidies to building contractors and to raise the realty values of slum areas, and not to furnish low-rental housing.

New York City is a good example of the fact that the rentals of the new housing developments will be prohibitive for workers even if they are employed. The Hillside Housing Corporation is to build 5,740 rooms in the Bronx at a cost of $6,084,000 with a PWA loan of $5,184,000. The rent per room will be $11 a month. In Queens the Dick-Meyers Corporation is planning to build 5,644 rooms at a cost of $4,168,940 with a government loan of $3,210,000. The rent here will also be $11 per room. The big Fred F. French Company which obtained $8,000,000 from the RFC for its Knickerbocker Village project is planning a monthly rental of $12.50 a room. Thus the rental of a 4 room apartment for the average family of five or six will amount to $45 or $50.

Such a rent figure is astronomical for working class families. A report issued recently by the Lavanburg Foundation illustrates this point clearly. They made an investigation of the 386 families who had been dispossessed by the Fred F. French Company from its Knickerbocker Village property. This slum area is the famous “lung block” which had been regarded as the “worst” in the city. The neighborhood was typical of the slum districts of New York. It is such slum areas that Lawrence Veiller, Secretary of the National Housing Association had in mind when he said that “the United States has probably the worst slums in the world.”

The Lavanburg Foundation discovered:

(1) That 79 percent of the 386 families had been able to pay less than $6 a month per room, and could only pay that sum by doubling up.

(2) That only 97 out of the 386 families had hot water.

(3) That only 119 families had private toilets in their flats.

(4) That only 25 families had bathing facilities.

(5) That not 1 family had steam heat or the equivalent.

The evicted families (86 percent) moved to adjoining blocks, and 319 families were forced to live in Old Law Tenements declared to be unfit for human habitation by the Tenement House Commissioner in 1900. Though all except 7 of the families expressed a desire to move into Knickerbocker Village, they were driven to their present rookeries because only 3 families were in a position to pay the high rentals of the model housing project.

For what group then does the administrator plan “model housing” which Ickes claims will be put “outside of com- petition with existing decent housing,” but will “unquestionably meet the needs of an income group never before accommodated.” Where in New York are there working class families that can spend $45 to $50 a month for rent? For that matter, how many working class families outside of New York will be able to pay the $25 monthly rental that is being planned in Detroit and other places. In 1932, it should be remembered, the Alexander Hamilton Institute estimated that the average annual wage of the employed worker was $640, about $12.50 per week. The NRA codes have seen to it that in 1933 and 1934 annual wages will be even lower. The rising cost of living will diminish real wages still further so that in 1934 the average worker will hardly be able to pay $10 a month for rent.

The present housing program, therefore, cannot benefit either the workers or large sections of the impoverished white-collar groups. The history of capitalism proves that workers could never afford to live decently. All slum clearance schemes, including the present one, never help the inhabitants of the slums, but the landlords and bankers. The workers are always forced to move to more intolerable rookeries. At the present time the unemployed, no doubt, will be forced to live in hovel-settlements and Hoovervilles. During the middle of the nineteenth century there were tens of thousands of German and Irish immigrants in New York who lived in shanty-towns along the Hudson and East Rivers. A similar barbaric fate is being prepared for the unemployed worker today.

The simple truth is that capitalism cannot provide decent housing for workers and employed or unemployed make a profit on it. The workers should demand, therefore, that the government stop handing out enormous subsidies to bankers and mortgage holders. They should demand that decent housing become part and parcel of an adequate relief system, and eventually of a national scheme of social insurance. Half of scheme of social insurance. Half of present day relief funds are spent for rent checks, which perpetuate slums that are hygienic and social sores. The government must condemn these tenements as a social evil, and appropriate money for workers’ apartments. The slums for workers’ apartments. The slums must be cleared without any deference to must be cleared without any deference to special privilege. Modern apartments, as part of a comprehensive building plan must be erected with space for parks, recreational centers, etc. The workers, through their unemployed organizations and trade unions, would participate in the planning, construction and maintenance of the buildings. Unemployed workers would get relief housing as part of general relief, or as part of unemployment insurance. Workers with jobs would pay only a nominal sum 5 or 10 percent of their wages. This is the only way in which workers can obtain decent housing under capital- ism-as a relief or social insurance right. Relief and municipal housing need not be “self-liquidating.” Its purpose would be not to roll up profits on rat-holes, but to provide adequate living quarters for unemployed and low paid workers. This workers’ control of new housing is the first step forward towards the eventual nationalization of all housing for the benefit of the workers, underpaid white collar groups, and poor farmers.

The New Masses was the continuation of Workers Monthly which began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Communist Party publication, but drawing in a wide range of contributors and sympathizers. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and The New Masses began. A major left cultural magazine of the late 1920s and early 1940s, the early editors of The New Masses included Hugo Gellert, John F. Sloan, Max Eastman, Mike Gold, and Joseph Freeman. Writers included William Carlos Williams, Theodore Dreiser, John Dos Passos, Upton Sinclair, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, Dorothy Parker, Dorothy Day, John Breecher, Langston Hughes, Eugene O’Neill, Rex Stout and Ernest Hemingway. Artists included Hugo Gellert, Stuart Davis, Boardman Robinson, Wanda Gag, William Gropper and Otto Soglow. Over time, the New Masses became narrower politically and the articles more commentary than comment. However, particularly in it first years, New Masses was the epitome of the era’s finest revolutionary cultural and artistic traditions.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/new-masses/1934/v10n05-jan-30-1934-NM.pdf