Charles Humbolet (Humboldt) reviews the first exhibit of the Artists’ Union held at Herman Baron’s American Contemporary Art gallery in 1935.

‘The Artists’ Union Show’ by Charles Humbolet from Art Front. Vol. 2 No. 3. February, 1936.

THE Artists’ Union has exhibited for the first time in a public gallery in group form. The show at the A.C.A. gallery is the result of the choice of a jury elected by the membership at one of its general meetings. It is, thus, fair to assume that the paintings there reflect not only the creative tendencies but also definite critical approaches to art within the union as a whole.

Quite apart from any question of individual merit, the paintings seem to be divided very sharply in their ways of treating scenes and experiences in general, or even what might be said to be the same scene. Two waterfronts, two workers, two street views of approximately the same subject matter will be dealt with in such different manner that a visitor might say, “Is this the same world I am looking at in both these paintings?”

These sharp divisions may be reduced essentially to one. On the one hand are those who believe that they may best render the world as they see it by “good painting,” that is by mastery of their craft in terms of certain traditions in painting. The tradition to which they attach themselves may be that of Rembrandt, Manet, Braque or any other master whatsoever. What matters is that these artists feel that objects and events are easier to handle with respect to their meaning, if they are linked beforehand to some mass of already achieved triumphs in the world of art.

The way Rembrandt or Picasso paints a beggar may help them to understand an outcast today. Chief among these artists are Moses Soyer, Abraham Harriton, Louis Ribak, and Ishigaki, too, in a sense.

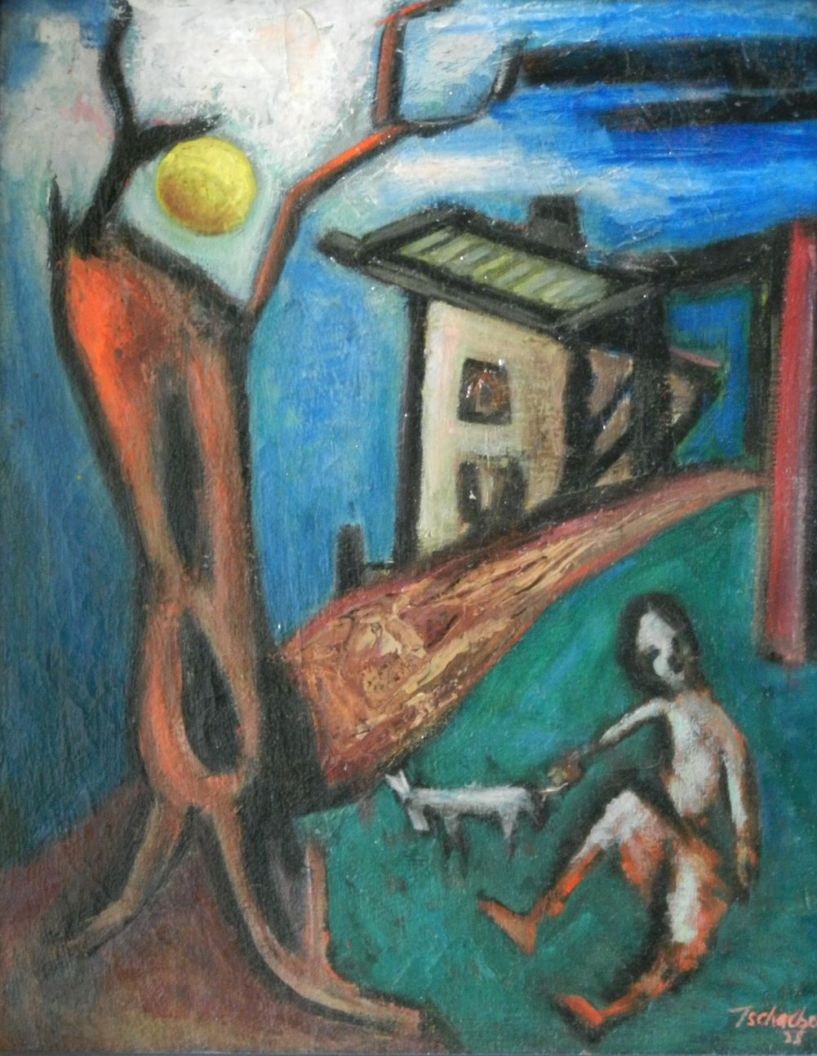

Opposed to these is an ever-growing body of artists who are prepared to forego momentarily many of their advantages as members of the society of acceptedly good painters. They are willing to take chances with their brushwork, their color, their space relations and their composition. They want to disregard some of the elements which most artists feel indispensable to any work that deserves the name of painting. (This is not a defense of bad painters. One speaks only of those who could obey the laws they violate.) Among these men are Tschacbasov, Haupt, Abbey and Mark. From seeing the Union show one is inclined to stake one’s hopes on the latter group.

The good painters seem often to have a technique unsuited to the things they intend to express. The picket lines are too finished, the houses of the poor a little too theatrical, the street scenes a little too orderly, the factory chimneys are gentle as poplar trees, the portraits are so settled–and Breugel would have painted differently had he lived in New England. One has no quarrel with mastery of craft, but only with the fact that this craft is used too abstractly, too much in and for itself regardless of the requirements of a particular subject. You can’t paint a demonstration with the same brush strokes and the same color you use for a house on a hill. The point is that, even if these painters attained perfect control of their materials; if they could do everything that it is possible for a great painter to do in the way of craftsmanship, they would still not have solved the problems that face the painter today. Just as Giotto, if he were alive and painted like Giotto, would not meet that problem. And no matter how sensitive a painter may be to moods, plays of light and shade, intimacies, atmospheres, his very sensitivity may itself become a sort of tradition within his own life, a tradition limiting his imagination and his ability to handle the coarser and more violent events that strike us daily.

The others are influenced too, but not in the same way. They are not pursuing one technique which will deal with all things one has seen, sees or may see. Rather they are testing numbers of techniques to find out which ones are effective for one and which for another situation. To the spectator this may appear to be copying; for the artist himself it is really a probing and discovery. Anyway young men have the right to imitate everybody, but older ones should not imitate even themselves.

The English, French and Russian revolutions were all revolutions, but were the same tactics used in all of them? Likewise the American revolution in painting needs techniques different from those of any tradition or other revolution in painting. New times, new struggles, new hopes, new methods.

When clothes are not as picturesque as they used to be, when the still life apples are all rotting unsold on the ground, and when the interiors are removed by the sheriff, then artists open their doors wide. They go into the streets to see what’s doing.

Art Front was published by the Artists Union in New York between November 1934 and December 1937. Its roots were with the Artists Committee of Action formed to defend Diego Rivera’s Man at the Crossroads mural soon to be destroyed by Nelson Rockefeller. Herman Baron, director of the American Contemporary Art gallery, was managing editor in collaboration with the Artists Union in a project largely politically aligned with the Communist Party USA.. An editorial committee of sixteen with eight from each group serving. Those from the Artists Committee of Action were Hugo Gellert, Stuart Davis, Zoltan Hecht, Lionel S. Reiss, Hilda Abel, Harold Baumbach, Abraham Harriton, Rosa Pringle and Jennings Tofel, while those from the Artists Union were Boris Gorelick, Katherine Gridley, Ethel Olenikov, Robert Jonas, Kruckman, Michael Loew, C. Mactarian and Max Spivak.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/parties/cpusa/art-front/v2n03-feb-1936-Art-Front-orig.pdf