Sen Katayama analyzes Hawaii’s unique history, its varied working class, and particular strategic position for U.S. and Japanese imperialism in the 1930s.

‘Hawaii, The Strategic Knot of the Pacific’ by Sen Katayama from Communist International. Vol. 10 No. 12. June 22, 1933.

THE Hawaiian Archipelago has twenty islands, only nine of which are habitable, and covers an area of 6,449 square miles. situated at the junction of routes across the Pacific. It is separated from the continent by over 2,000 miles (from San Francisco to Honolulu 2,418 miles, from Panama 5,395 miles, from Manila 5,429 miles and Yokohama 3,915 miles).

Though the territory is small, nevertheless the Hawaiian Islands form the most important strategic point in the Pacific Ocean. With the growth of the danger of imperialist war, the thunder clouds are hovering low over the Pacific Ocean the interventionist plot against the U.S.S.R., the war in China, the ripening military conflict between the U.S.S.R. and Japan, etc. North American imperialism is making the fullest preparations to utilise these little islands, which are a colony of the U.S.A., for its war aims. The repeated big naval manoeuvres in the Hawaiian Archipelago, the concentration of the Atlantic fleet of the U.S.A. in the Pacific Ocean, the proposed militarisation of Hawaii, etc., are all facts which speak sufficiently for themselves. The Japanese imperialists are likewise not lagging behind in their efforts to use the Hawaiian Islands in their own interests, arguing that the majority of the population on Hawaiian territory are of Japanese origin. The agents of Japanese imperialism in the government circles of Hawaii, the representatives of big firms, newspapers, etc., use every effort to implant patriotic chauvinistic feelings among the Japanese population of the islands. Rumours circulate as to the nearness of the Japanese-American war, a permanent place is taken by agitation for a further advance on China, and a war of intervention in the U.S.S.R. The Japanese imperialists have even sent their “labour” agents in the person of the “left” social-democrat, Professor Oyama, to Hawaii for the purpose of finding an approach to the toiling Japanese population of the islands.

The Japanese press publish reports of debates in Congress emphasising the great importance attached by American imperialism to the Hawaiian Archipelago in the Japanese-American war:

“Last year (May 18th, 1932) a bill was introduced into Congress to appoint an army or naval officer as governor of Hawaii. It was emphasised that, in the future, the day would undoubtedly arrive when the lives of American citizens would depend on military action. developed around Hawaii. From this point of view we propose, together with Panama, to subject Hawaii to complete and direct military control because this is a most important line for the defence of the U.S.A. Enemies cannot approach us from the East without first destroying the line of defence and the naval base at Hawaii.”

In giving this quotation, the Japanese paper points out that, up to now, the governor of Hawaii has been elected from among the Americans living on the Hawaiian Islands.

HOW AMERICAN CAPITALISM SEIZED HAWAII.

The process of colonisation of the Hawaiian Islands is a classic illustration of the reactionary role played by Christian missionaries in support of the of the imperialist policy of colonial plunder. The Hawaiian Islands came under the influence of American missionaries in 1820. A considerable part of the native population adopted Christianity. With the active help of these missionaries, who cleverly utilised the discontent of the native masses with their rulers, the U.S.A. staged a “revolution” in 1893, and drove King Liliuo-kalani from the throne. As the attempt at immediate annexation of the islands broke down, on July 4th, 1894, a “republic” was proclaimed, under the “protection” of the U.S.A. navy, while in 1900 the islands were “officially” annexed by the United States. On the grounds that there were large numbers of Japanese emigrants in the islands, Japanese imperialism attempted to interfere in Hawaiian matters, but these attempts were frustrated by the U.S.A.

Since the occupation of the islands, the best part of the land has been seized by the American bourgeoisie, especially by American missionaries. It is interesting to note that many of the rich Americans who now own sugar plantations on the Hawaiian Islands are descendants of these “messengers of Christ.” The Hawaiian Archipelago became an American colony, a source of wealth to the imperialists of the U.S.A. at the expense of the natives and the immigrant workers, chiefly Japanese, Filipino and Chinese.

Hawaii is one of the centres which supply the U.S.A. with sugar. In 1920-21 the U.S.A. imported from Hawaii 977,738,902 lbs. of sugar and in 1927-28, 1,647,586,758 lbs. In 1926-27 the amount of pineapples (the second in importance of the products grown in the islands) exported to the U.S.A. was 410,570,322 lbs. The U.S.A. exports to Hawaii chiefly iron and steel goods, mineral oil, meat, fertilisers, etc. In 1927-28 the total amount of American exports into the Hawaiian Islands was $78,585,650 (Hawaiian exports to the U.S.A. in the same period were valued at $113,547,157). According to an approximate estimate, from 1900-25 the Hawaiian Islands paid $117,195,205 into the U.S.A. treasury. The U.S.A. government has officially established a big military post in the islands with accommodation for 30,000 men in Schofield and several secondary posts. The naval ministry has a big base at Pearl Harbour with dry docks, opened in 1919. Here also are big hangars for airplanes and a powerful radio station. Since 1925, a national guard has been organised on the Hawaiian Islands, the numbers reaching 1,727 men in June, 1928 (102 officers and 1,625 volunteers). People of various nationalities, including those of Eastern origin, are taken into the national guard.

The ports of Hawaii are maintained by direct taxation and special loans from the population to the sum of several million dollars. Hawaii is covered with a network of excellent railroads.

From 1901-25, over 25,000,000 dollars were expended in building the chief lines, which, of course, are of great strategic importance. It is interesting to note that of 1,038 miles of railroad in Hawaii in 1926, about 700 miles or about 70 per cent. of the whole system passes through plantations, which clearly illustrates the specific colonial character of railroad construction in Hawaii. On the one hand, there are strategic military lines and on the other there are lines adapted to the easiest extraction of the specialised agricultural products of this colony for the main country (sugar and pineapple).

THE POPULATION AND ITS RACIAL COMPOSITION.

The population of the Hawaiian Islands–Polynesian–at the time of their discovery by Captain Cook in 1778 was about 200,000.

“But together with civilisation,” states the “World Almanac,” “the population fell, and eventually the Polynesian race disappeared, rather owing to mixed marriages and other causes than extinction.”

The falseness of this statement is obvious, as the Almanac admits that the death rate among the Hawaiian population was 30 per cent. and that the whole population of the Hawaiian Islands, including those who had made mixed marriages, was 49,143 in 1929. The cause of this rapid fall in the numbers of the local population must be sought elsewhere. The fate of the American Indians, Japanese Ainu, victims of the barbarity of imperialist plunder, form a complete analogy with the fate of the peoples of the Hawaiian Archipelago.

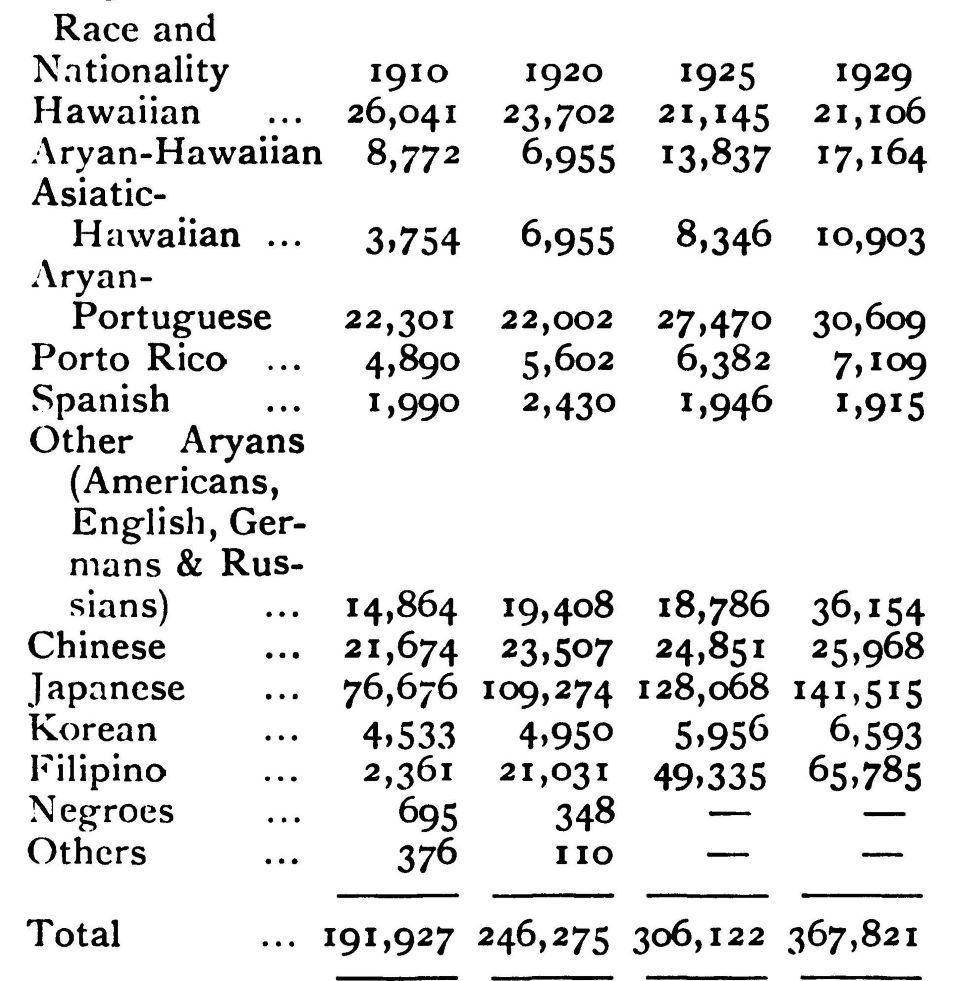

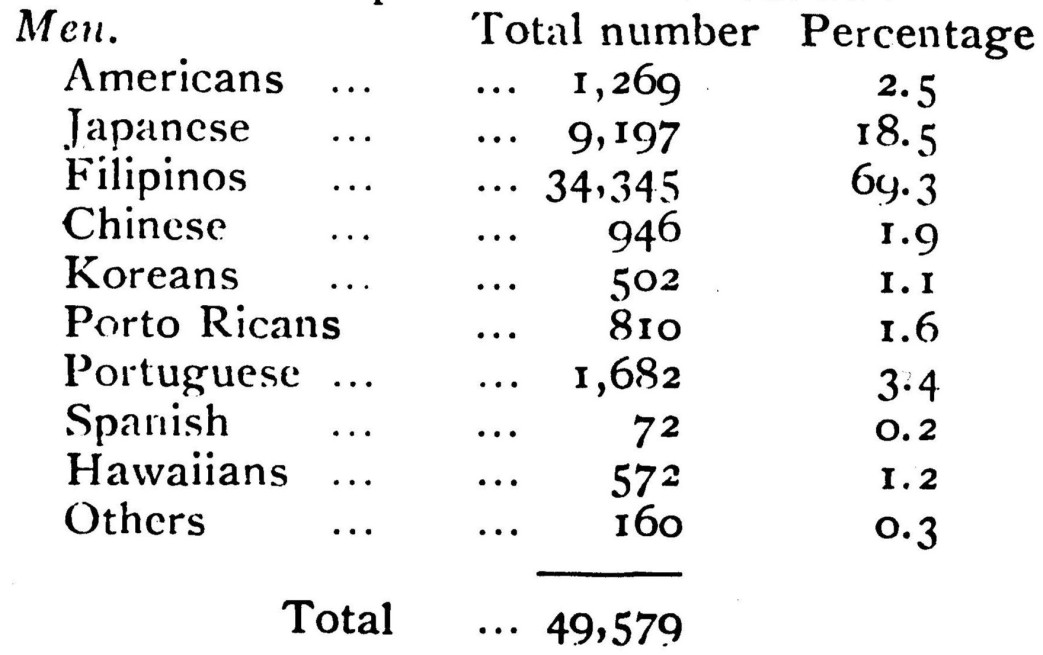

In contradistinction to the American colonies and to other colonies of the same type, the majority of the population in the Hawaiian Islands does not consist of locally born people who inhabited the country before its conquest, but of masses of emigrants. It is a mixture of different nationalities, as we shall see from the following table. It is of great importance that about 40 per cent. of the population are Japanese. This fact emphasises the role of Hawaii in the approaching conflict between the U.S.A. and Japanese imperialism. At the same time it creates a complex situation and makes the work of Communists difficult in the organisation of the independence movement in Hawaii.

Note. These figures do not include the naval and military forces of the U.S.A.

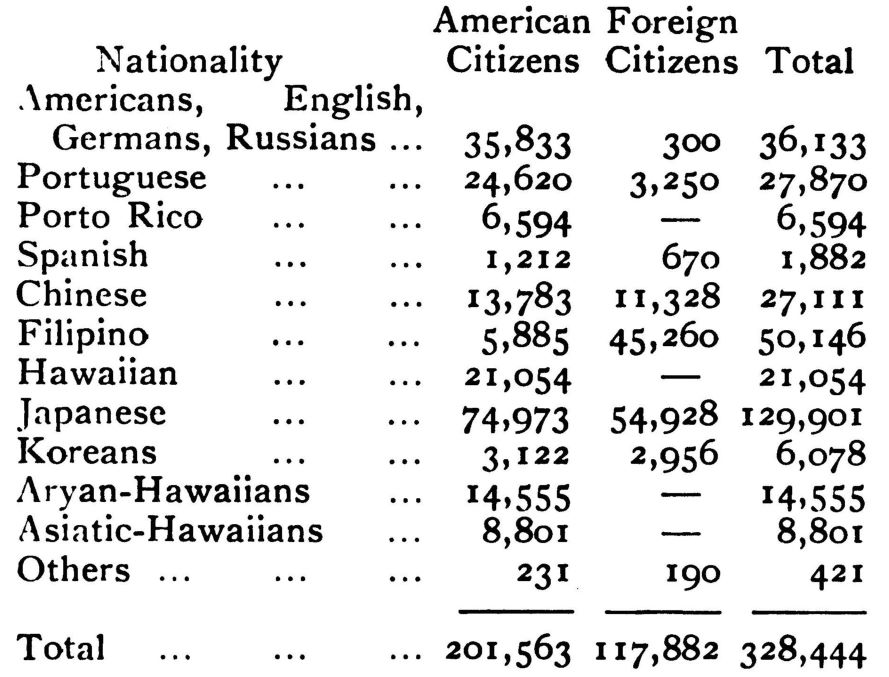

The national composition of American and foreign subjects in 1926 (according to the Statistical Bureau “Vital Statistics”):

Although the proportion of Americans and Europeans is very small, nevertheless, as pointed out above, they practically rule the whole of the industrial and political life on the islands. The following table is significant from this point of view:

Tax Assessment of the Population. (Report of the Governor in 1926.):

Americans and Europeans. $9,951,412.48

Hawaiians (including half-breeds) 1,098,803.54

Chinese 613,593.87

Japanese 656,236.42

Filipinos 158,119.35

The number of voters does not correspond to the number of the population. During the local elections in 1926 only 40,569 persons voted. By nationalities they were divided as follow: Hawaiians and semi-Hawaiians 11,763; Americans and Europeans 15,540; Japanese 3,094; Chinese 2,906; others 12,068. In 1926, during the elections in Honolulu district there were 4,000 citizens of Japanese extraction who had the right to vote, but only 1,800 actually voted.

Harada, the Japanese professor at the Hawaiian University, wrote as follows in his book, “The Social Position of Japanese in the Hawaiian Islands,” published in 1927:

“In 1920 a Hawaiian made the following statement at an official meeting in Washington: ‘In seven years the majority of the voters in the Hawaiian Islands will be Hawaiian-Japanese, and if the Americanisation of the Archipelago is not completed, the Hawaiian Islands will be under the power of the Japanese government.’ Exactly seven years have gone by since this forecast, but we find that the Hawaiian-Japanese are far from being the majority of the voters The fact is that the majority of the second generation of Japanese in the Hawaiian Islands are still very young, and only a small fraction of them have reached the age of twenty-one, i.e., the age which gives them the right to participate in the elections.”

In spite of these words of Harada, which seem so comforting to the U.S.A., there are real motives which incite the American imperialists to raise hysterical howls about the “yellow peril” and the “danger of Japanese violence.” The agents of Japanese imperialism in the islands are establishing special Japanese schools where they inculcate Japanese culture, teach the scholars the Japanese language and the religion, but at the same time send them also to the American schools. Many of these youngsters are sent to Japan for special “Japanese training. There are several Japanese senators, who were born in the Hawaiian Islands, and many local officials. All these are elements on which Japanese imperialism can rely. The Japanese imperialists are trying to make the greatest use of the “favourable situation. Senator Yamashiro, a Hawaiian-Japanese, reporting on the proposed militarisation of the Hawaiian Islands, prophesied the growing force of Japanese influence in the islands, stating that: “At present there is only talk of the militarisation of Hawaii, but these words may become deeds, as the strength of the Japanese here is growing” (“Los Angeles News” in Japanese, July 15th, 1932).

CHIEF BRANCHES OF HAWAIIAN INDUSTRY.

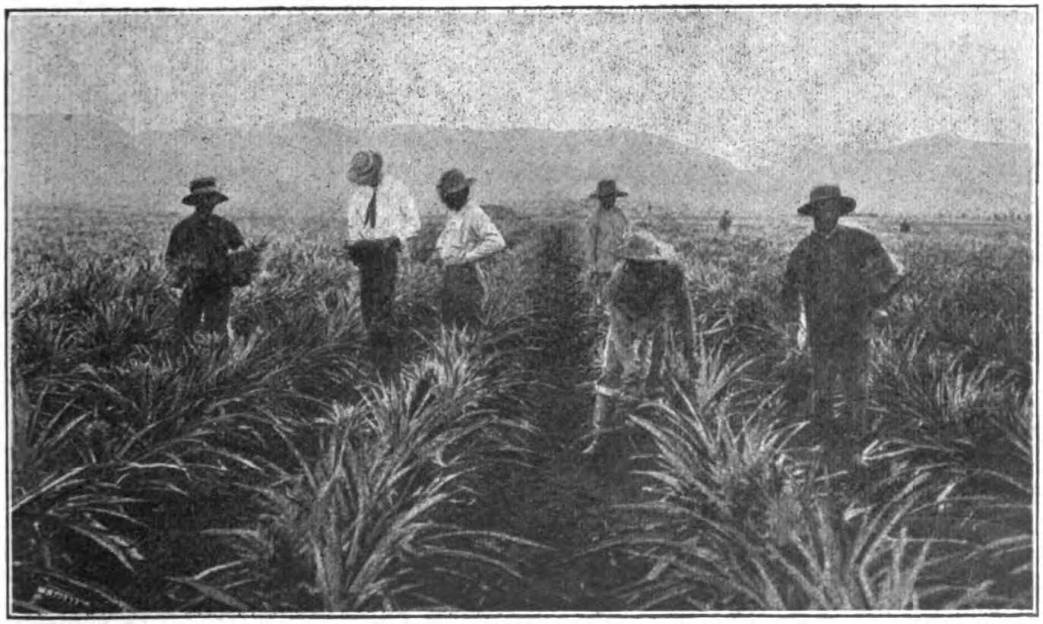

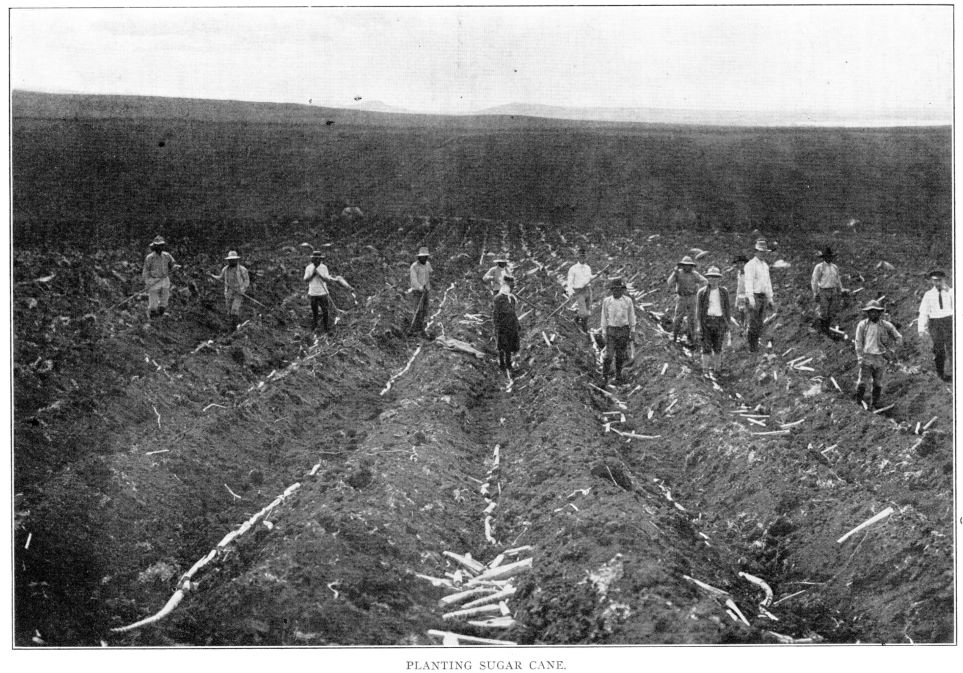

The cultivation of sugar and pineapple is the main branch of economy in the Hawaiian Islands. The output of these products has increased 100 times since the annexation of the islands by the U.S.A. Rice, coffee and bananas are also grown. Animal rearing is widely practised.

The output of sugar in 1882 was 57,088 tons. In 1900 it was 289,554 tons, in 1929, 913,670 tons. In the same way the output of pineapple increased from 2,000 cases in 1901 to nine millions in 1929.

THE WORKERS IN THE SUGAR AND PINEAPPLE PLANTATIONS.

1. National Composition.

Whereas the dominating role, especially in the sugar plantations, was previously played by the Japanese workers (in 1908 there were 38,711 Japanese workers in the sugar plantations), this role is gradually passing to Filipino workers. This does not mean that the Japanese immigrants have been sent back to Japan. The fact is that the heavy conditions of labour on the plantations, the unlimited exploitation, results in the rapid exhaustion of labour power and compels a constant import of fresh immigrants who can be paid still cheaper. Therefore, according to the report of the Governor in June, 1929, the workers in 41 plantations of the Hawaiian Association of Sugar Planters (controlling the whole of the sugar industry on the territory of the Hawaiian Islands with insignificant exceptions) numbered in all 56,658. Their national composition was as follows:

According to the report of the Statistical Board of the U.S.A. in 1929, there were 7,512 workers (3,933 men and 3,579 women) in the pineapple canning factories, and in the same year there were 3,577 workers on the pineapple plantations (3,416 men and 161 women). These figures are plainly below the real state of affairs. It is possible that day workers are not counted at all. According to the same report, there were 4,285 workers in the rush season in 1929 on two big pineapple plantations alone.

The national composition of the workers on these two plantations gives a general picture of the distribution according to nations: Japanese 35 per cent., Chinese 4.7 per cent., Filipinos 65 per cent., Hawaiians 0.8 per cent., Koreans 3.4 per cent., Others 3.6 per cent.

The following figures show the national composition in a big pineapple canning factory in Honolulu Japanese 42.1 per cent., Chinese 9.7 per cent., Hawaiians 16.4 per cent., Portuguese 7.6 per cent., Filipinos 11.7 per cent., Americans 2.6 per cent., Others 0.9 per cent.

In the above-mentioned branches of industry the majority of the Americans work as engineers or skilled workers. Some of the skilled workers are Hawaiians and people born in the Far East. It is quite obvious that the majority of the unqualified workers are natives of the Far East, chiefly Filipinos and Japanese.

2. Wages and the Working Day.

The average working time in a week in these branches of industry is sixty hours. The working day lasts ten hours, according to the report of the Statistical Board of the U.S.A., but frequently is it dragged out to twelve hours.

The average daily wage in the sugar plantations and factories in 1929 was $1.84 for men and $1.30 for women and $0.87 for children. The full wages for a week were $11.04 for men and $7.80 for women. It is very difficult and dangerous to believe these figures which are given by the are given by the government. The “average” wages in these statistics is a very obscure quantity, because it evidently includes the much higher wages of the

European managers and technical staff. A piece-work system of wages is operating in the plantations, and the above-mentioned figures probably apply to those workers who work on the system of so-called participation in profits. The same applies to the pineapple industry.

In the pineapple plantations the average wages in 1929 were $1.90. The weekly wages for men were $13.62 and for women $6.96. In the canning factories the average wages in 1929 were $1.65. The weekly wages of men were $16.26 and of women $10.08. We should be extremely sceptical of this official “average” figure. In addition, during the economic crisis of 1929-1933, even these wages were greatly reduced.

The workers in the sugar plantations “receive apartments, heating, water and medical help free. They receive their basic monthly wages, and a premium which varies according to the price of sugar,” says the government report. If we translate this into ordinary language, it means that the workers in the plantations are compelled to work in conditions of forced labour, of a long working day, for low wages, in miserable barracks. The premium is merely the sugar coating to the low “basic monthly wages.” In addition, a loophole is left. “The premium varies according to the price of sugar.

The general income of such a worker may be calculated by multiplying the daily wage by 365 minus rest days, and there are very many of such unpaid rest days. The sugar season lasts less than eight months, and the pineapple season only four months. It is counted very good if a worker, on the whole, is employed for sixteen days in a month in the pineapple plantations. This is shown by the turnover of labour power in these branches, and also the fact that, with the exception of Americans, the majority of the workers are not on monthly wages. As we have already mentioned, the American workers are mostly skilled workers and mechanics.

Night work or overtime is not paid. In addition, there are “elders” who act as an intermediary between the plantation owners and the workers. The workers can only get work through the “elders” and this creates a double burden of exploitation for them. These apply especially to the Japanese and Filipino workers. These elders not only control work and wages, but also living quarters and food, for which the workers are compelled to pay monstrously high prices.

HAWAII AND THE CRISIS.

The crisis has severely affected the Hawaiian Islands, with their single crop farms, and the bourgeoisie are trying to throw the whole burden of the crisis on to the shoulders of the toiling masses. The output of canned pineapple has fallen by half, and last year there were rumours that the Philippine Canning Company would soon wind up its business. There are no other figures on the crisis in this industry. But without doubt the situation of the workers in the pineapple canning industry has worsened. There are mass dismissals, they are not paid their wages, pay is being cut, premiums abolished, the intensification of labour introduced, etc. Small farms which grow pineapples are also seriously affected by the crisis.

“The small Japanese farmers who produce pineapples on Saku Island,” writes the newspaper “Los Angeles News” on July 9th, 1932, “in view of the closing of the canning company are deprived of the possibility of selling their products. The harvest on which so much labour was expended is rotting as it stands, and their families are starving.’

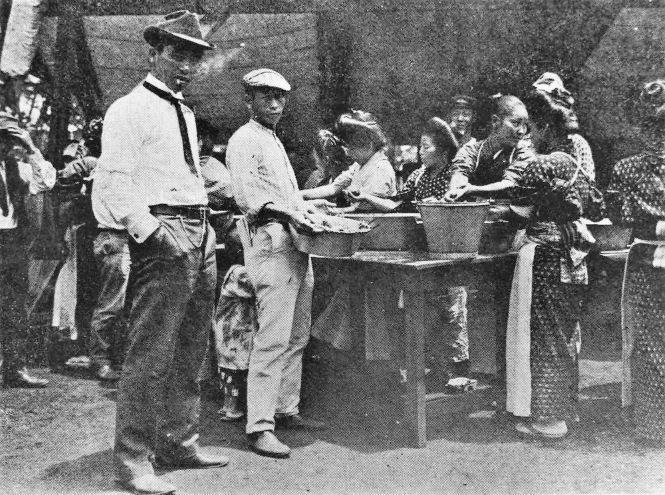

shelters provided for them in Kaka‘ako and Mō‘ili‘ili, Honolulu, Hawai‘i. 1909.

There can be no doubt that the same applies to the condition of the sugar industry. The workers employed in the sugar plantations and the sugar factories are in a difficult situation. We have no concrete information on the effect of the crisis in the Hawaiian Islands, the winding-up of industry, the amount of the wage cuts, the intensification of labour, unemployment, the bankruptcy of small farmers and shopkeepers, so that we can only judge on the basis of scattered information which appears from time to time in the bourgeois press. But even the bourgeois papers admit the growth of the army of unemployed in the Hawaiian Islands. Even in autumn, 1931, a Japanese bourgeois paper “Hawaii Hotsi,” which is published in Hawaii, wrote that thousands of Japanese workers cannot find work and are flocking to towns like Honolulu.

SMALL FARMERS.

In 1920, out of 5,280 farms on the territory of the Hawaiian Islands, 882 belong to whites (627 owners), while 3,098 belong to Japanese (188 owners, eleven managers and 2,899 tenants). These farmers are mostly Japanese peasants growing rice, coffee, sugar and pineapples. They are forced to sell the two latter products to the big sugar and pineapple companies at low prices. fixed by these companies.

THE TWO CHIEF FACTORS ON THE HAWAIIAN ISLANDS-JAPANESE AND FILIPINO WORKERS.

The leader of the Hawaiian Association of Sugar Plantation Owners stated cynically that the chief reserves of labour power for them are Japanese and Philippine workers because they do such hard work, on such small wages, that Americans or white workers in general cannot rival them. At first Japanese workers predominated, and still play a very important role. They immigrated in large numbers and became a menacing spectre of the yellow peril,” both in the United States and on the Hawaiian Islands. However, a law was passed prohibiting the immigration of Japanese, and since then the planters have begun bringing hundreds of Filipinos, with whom they make contracts guaranteeing them “free passage back to Manila if they work a certain minimum time.” With the aim of “identifying” them, their finger prints are taken like criminals. However, at the present time, a howl has been raised regarding the “growing danger from the Filipino workers.” This howl is going up from the American Federation of Labour and other elements, both in the U.S.A. and in the Hawaiian Islands.

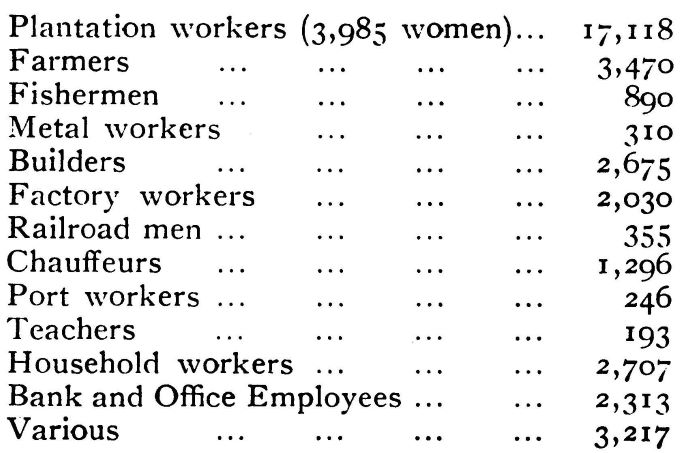

According to the “North-American Annual,” the Japanese population of the Hawaiian Islands (persons having an independent wage) in October, 1925, was distributed among the following professions:

Of course, these figures are by no means exact, but nevertheless they enable us to judge the general tendency. The Japanese population of Hawaii, and also of many towns on the west coast of the continent have special sections of the town, their own banks, schools, temples, etc., not to speak of thousands of Japanese stores in which Japanese store-clerks work.

As for the Filipino workers, 43,433, or 64 per cent. of the total Filipino population of the Hawaiian Islands work on the sugar-cane plantations. Five thousand work regularly on the banana plantations and 6,500 to 12,000 work at the pineapple factories, etc.

PERSECUTION OF THE TOILERS OF HAWAII.

We have no information of the exploitation and the persecution of the native masses of the Hawaiian Islands, also we do not know whether there is an independence movement among them, in what form it shows itself, or how. However, there can be no doubt that the majority of the Hawaiian native bourgeoisie, the landlords and descendants of the royal dynasty, are entirely in the pockets of the American imperialists and collaborate with them, to exploit the masses of toiling natives.

The recent lynching of Hawaiian and Japanese youths who were caught by an American officer and his relatives, the so-called Massie case, the encouragement given to such lynchings by the Hoover régime and the limitation of freedom of action for native jurors during the trial of this case in court (introduced by such a “liberal” lawyer as Clarence Darrow, who was defending counsel in this case), show what restrictions were and are applied to the Hawaiian toilers. In particular, these attempts to justify lynching in Hawaii have caused great excitement among the toiling masses of Hawaii, although they have not made attempts at organised protest.

On the Hawaiian Islands, strict restrictions are practised towards Negroes, and for this reason the plantation owners refuse to bring workers from Porto Rico. They say: “Negro blood flows in the veins of many of the workers of Porto Rico.”

In spite of their large numbers, the Japanese population of Hawaii are also subjected to every kind of social, economic and political restriction, which, it is true, does not apply to the rich Japanese who live on the islands. With regard to Filipinos, Chinese and other toilers, the attitude towards them is still worse. We are informed that the Young Men’s Christian Association refused to take in Japanese or Chinese youth, on the grounds that there is no place for them in a “white” organisation. The rich Japanese and religious fanatics were greatly excited at this, but the end of the matter was that they formed a separate Y.M.C.A. for Japanese youth.

It is noteworthy that the yellow reformist organisations of white workers on the Hawaiian Islands refuse to accept Japanese, Filipino and other Far Eastern workers. With regard to the latter, there are restrictions also in the matter of wage scales, housing conditions and the type of work given them. In 1920 the Japanese struck against low wages and bad housing conditions on the sugar cane plantations, obtaining a partial victory. The persecution of Filipino workers is still worse.

WORKERS’ ORGANISATIONS.

The Statistical Board of the U.S.A. writes as follows in its report on the Hawaiian Islands (No. 534) regarding workers’ organisations:

“In Hawaii there are few workers’ organisations and their membership is small, with the exception of the hairdressers’ union. They have no wage agreements with the employers. Mechanics, pattern-makers, pattern-makers’ helpers and boilermakers in the metallurgical and machine construction plants have organisations. This applies also to type-setters and linotype operators in the printing industry, ship-mechanics, carpenters and joiners, plasterers and rivetters in the building industry and repair work, and also hairdressers, except Japanese and Filipinos.”

Although it is not stated, we must suppose that the Hawaiian trade unions belong to the reactionary A.F. of L., or, at any rate, support its platform, especially on the question of restricting the rights of Far Eastern workers.

In the same report is said that, in Honolulu, there are about 1,000 Japanese carpenters who do about 90 per cent. of the carpentry of the town for wages of $3.50 a day, while union carpenters demand $6.50 and an eight-hour day. However, the report does not make the slightest mention of the large number of strikes of Japanese and Filipino workers in the sugar plantations which took place in 1920-1925.

In 1927-28 over 5,000 workers employed on some sugar cane plantations on Oahu Island came out on strike, with demands for equal wages and housing conditions with the white workers. The strike spread to other plantations and threatened to spread to all the plantations of the island. It lasted over a month and ended in the victory of the strikers. The strike was led by Japanese journalists and business men from Honolulu and was supported by all the Japanese residents of this town, who collected money, housed the strikers, organised food kitchens, etc. Naturally, the leaders of the strike were not so much interested in defending the interests of their “fellow-countrymen,” although they continually declaimed about this, as they were interested in utilising the discontent of the Japanese workers to develop a struggle against their competitor, American capital, for the benefit of the Japanese bourgeoisie. The leaders of the strike were sent to jail for several months. During this strike, no attempt was made to draw the workers of other nationalities into the struggle, although they, especially the Chinese workers, employed on the plantations, sympathised with the strikers. After the strike, a Japanese workers’ association was formed, which about 5,000 workers joined, but later it collapsed.

The strike of the Filipino and Japanese workers in 1925 aimed at securing wage increases. The workers struck for “an increased minimum daily wage, says Bruno Lascar in his last book on the immigration of Filipinos to the U.S.A. and the Hawaiian Islands (1931). They demanded that “the conditions of work should approximate to those in the big farms of the U.S.A.” The strike was defeated. During the strike, five policemen and fifteen strikers were killed in a clash. After this, the Filipino governor appointed a commissar on workers’ affairs in Hawaii, who carries on negotiations with the planters and the Filipino workers, striving to keep the latter in subjection.

The leader of the strike was a Filipino lawyer Pablo Manlapit. He was sent to the Hawaii prison for several years, after which he left for the U.S.A. At first he showed sympathy with the C.P.U.S.A. and the Anti-Imperialist League, which at that time (1927-28) was carrying on an active campaign for the independence of the Filipines. However, he then informed the correspondents of the papers that he had nothing in common with the League, and the position he set forth in this interview with the correspondents differs in no way from that of the national bourgeoisie. Since his arrival in the U.S.A. he has lived in Los Angeles, and did not participate in the organisation of the strike of the Imperial Valley plantation workers, and many other strikes of farm workers in which Filipino workers took an active part.

However, according to the latest information, Manlapit last year once again began to carry on active work among the Filipino workers in the Hawaii plantations. The newspaper “Rodo Simbun” (organ of the C.P.U.S.A., published in Japanese), taking into account the past history of this man, says that “Manlapit is probably a spy.” As for his further organisational work in the movement of the Filipino workers in Hawaii if such a movement exists, we have no material making it possible for us to make any decision. It is true that we know that last autumn 200 unemployed Filipinos held a spontaneous demonstration and organised a march to the municipal buildings of Honolulu, and this is sufficient to show that a ferment is also taking place among the Filipino workers.

The Koreans have their organisation on the islands, “Korea Mindan” (the Korean national organisation), which publishes a newspaper and has wide international contacts. However, it is a diehard nationalist group under the influence of Christian missionaries, and penetrated with the ideology of the Korean national bourgeoisie. It is difficult to judge the degree of influence of this group among the Korean workers on the islands.

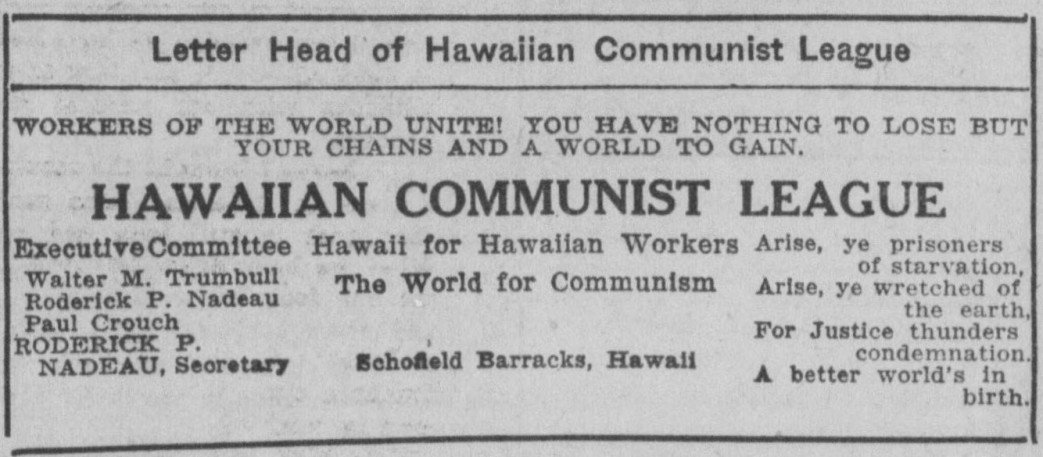

Among the Japanese workers in Hawaii there was a group which was long under the influence of the Japanese revolutionary movement. The members of the group came chiefly from the Japanese islands of Riu-Kiu, where, at one time, the Japanese Workers’ and Peasants’ Party (which supported the C.P. Japan, and was dissolved by the government in 1928) had a strong influence. This group remained, for a long period, without contact with the masses, but in 1930 it began to take some active steps. As a mark of protest against the arrival of Major-General Kanna from Riu-Kiu in 1930 there was a collection of money for the election fund on Maui and other islands, and the organisation “Yuaikai” was formed with over 200 members.

Later the Hawaiian Proletarian League was organised, a group for studying sociology in the Hawaiian University and a literary group around the journal “Hagurum” (The Cog Wheel). maintained close contacts.

The arrival of Professor Oyama, who at one time sympathised with the C.P. Japan and is now one of the wildest social-fascists, caused a split among these elements. The majority were on the side of Oyama, held mass meetings, gave a banquet in his honour, etc.

The minority, consisting principally of youth, energetically fought against him. This was in summer, 1932. In autumn, after Oyama had been exposed by the American workers as an agent of Japanese imperialism, that part of the League which had split away, again joined up and organised “Hawaii Musansia Higogikai” (Hawaiian Proletarian Soviet). At the present time it has 2,500 members and branches on five islands; Oahu, Hawaii, Maui, Kawaii and Molokaii.

The intensification of the crisis is driving American imperialism to further increased exploitation and oppression of its Hawaiian colonies. As the preparations of the international imperialists for anti-Soviet intervention progress and the clouds of imperialist war gather over the Pacific Ocean, North American imperialism will still more definitely carry out its military control of the Hawaiian Islands, At the present time, the militarisation of Hawaii is on the order of the day, and American imperialism takes account of the role which this colony may play. But Japanese imperialism is also trying to strengthen its influence in the Hawaiian Islands, and there was good reason for the social-fascist Oyama going there. The objective situation is favourable for the development of work among the revolutionary elements on the Hawaiian Islands, the more so as the discontent of the masses is growing, as is shown by the formation of the Hawaiian proletarian council by the workers, and also by the demonstration against unemployment organised by the workers.

The C.P.U.S.A., the Japanese and Filipine C.P.s, but especially the C.P.U.S.A., must give the greatest help to the liberation movement of the toiling masses in Hawaii.

The immediate tasks of the revolutionary movement in the Hawaiian Islands are determined by the specific social and economic conditions and the international situation of this colony.

1. The main island is of exceptional naval strategic importance in the approaching war between the basic imperialist powers on the Pacific.

2. The whole economy of the Hawaiian Islands is adapted to the interests of American finance capital and the military aims of American imperialism.

3. American imperialism, having converted the Hawaiian Islands into a classic agrarian appendage for producing raw material, implanting the plantation form of agriculture for the more successful pumping out of the raw materials and products needed by it, at the same time has maintained and conserved the most barbarous form of pre-capitalist exploitation, feudal exploitation, combining it with modern “civilised” forms of indentured semi-slave labour on the plantations and in the factories.

4. The specific nature of the social conditions of the Hawaiian Islands are, firstly, that it is difficult to establish any definite native national mass, typical for most colonies. Here, in the Hawaiian Islands, it is American imperialism which dominates economically and militarily. Its rival, not only in the general economic and military sense but in the direct internal economic sense, is Japanese imperialism, which has such an important means of influence as almost half the population of the Hawaiian islands. American imperialism, of course, exploits all the population of Hawaii. But in addition to the usual differentiation of classes and class contradictions, we here find an unusual phenomenon of the national-race factor, which is utilised with fair ability by American and Japanese imperialism in their interests (the Hawaiians form only 15 per cent. of the population, Japanese over 40 per cent., Filipinos 20-25 per cent).

5. This circumstance has its effect on the workers’ movement and the organisational forms of the revolutionary movement.

Here in a preliminary article (as we have not many important facts concerning the peasants, the prevailing forms of economy, the existing national liberation and revolutionary movement, tendencies, organisations, etc.), we merely wish to indicate the direct tasks which plainly rise for the revolutionary elements in Hawaii:

1. Firstly, it is necessary to start to organise mass revolutionary trade unions; and, above all, among the workers of the sugar, pineapple and transport industries, and also among the farm hands. These trade unions at the given stage will evidently have to be constructed according to nationalities (Japanese T.U.s, Filipino T.U.s, etc.) with a leading centre to unite them (the central trade union council). There are undoubtedly many difficulties and dangers with such organisational forms (race and national differences and chauvinism, the inevitable attempts of Japanese and American imperialist agents to get possession of these unions, etc.). But while building these unions at first according to nationality, linking them up in a unifying centre, it will be necessary to follow the course of an international union of T.U.s.

2. At the same time a firm united Communist group (or Party) must be formed, which will include Communists of all nations, and which would guide the trade unions and the revolutionary mass movement in general.

3. The immediate slogans and demands in the every-day practical struggle of the masses, under the leadership of the Communist groups, must be concentrated around the question of conditions of labour (the eight-hour day, equal pay with white workers, defence of labour, etc.), demands for elementary political freedom (freedom of press, organisation, assembly, electoral rights, etc.). Special demands must be worked out for farm hands, plantation workers, tenants and poor peasants (taxes, rent conditions, etc.). In addition concrete demands must be prepared in the sphere of national, cultural freedom and equality (teaching the national language to the given group of the population, equality in political and cultural respects, etc.).

4. The Hawaiian revolutionary movement must be linked up with the revolutionary movement in the U.S.A., Japan, and the Philippines.

The ECCI published the magazine ‘Communist International’ edited by Zinoviev and Karl Radek from 1919 until 1926 irregularly in German, French, Russian, and English. CI contained long-form articles by the leading figures of the International as well as proceedings, statements, and notices of the Comintern. No complete run of Communist International is available in English. Both were largely published outside of Soviet territory, with Communist International printed in London, to facilitate distribution and both were major contributors to the Communist press in the U.S. Communist International and Inprecorr are an invaluable English-language source on the history of the Communist International and its sections.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/ci/vol-10/v10-n12-jun-22-1933-CI%20grn-riaz-OC.pdf