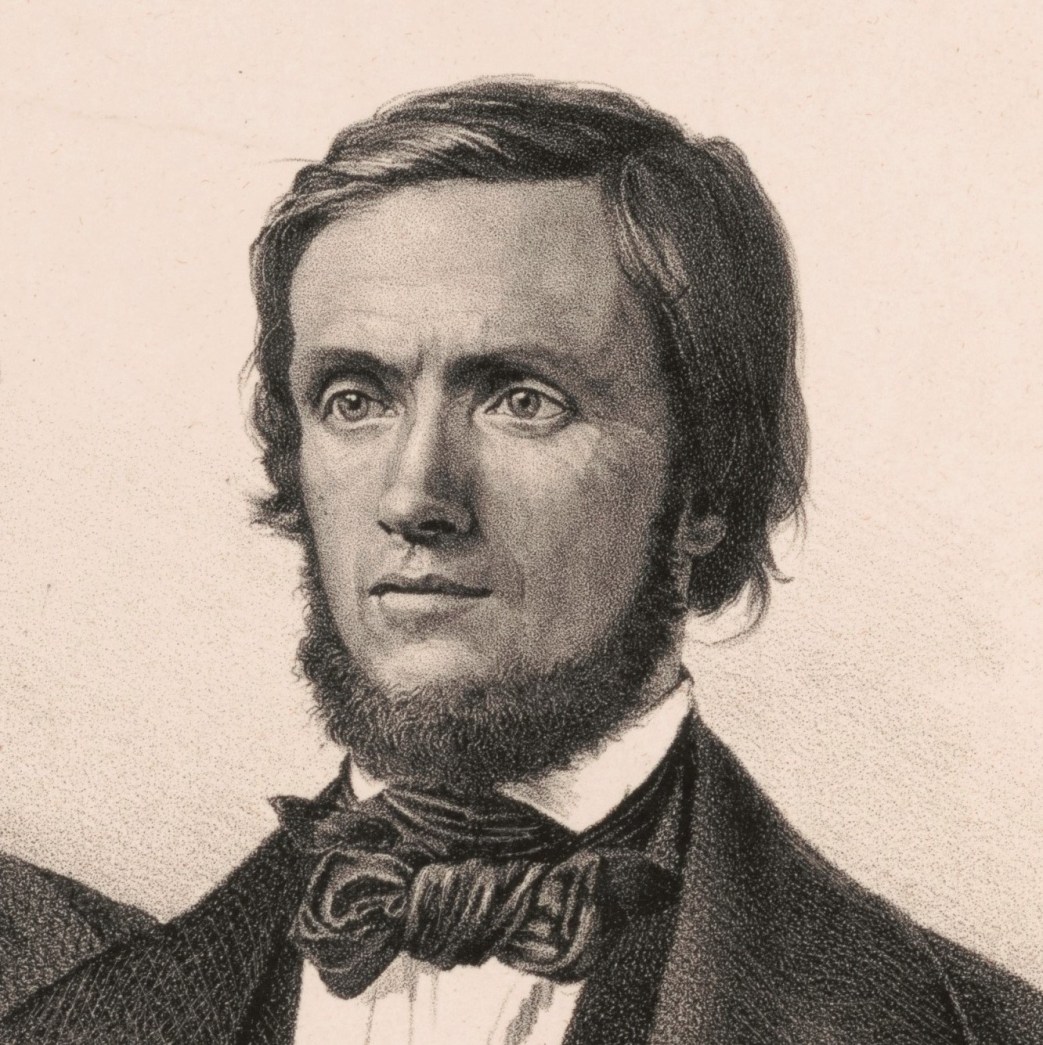

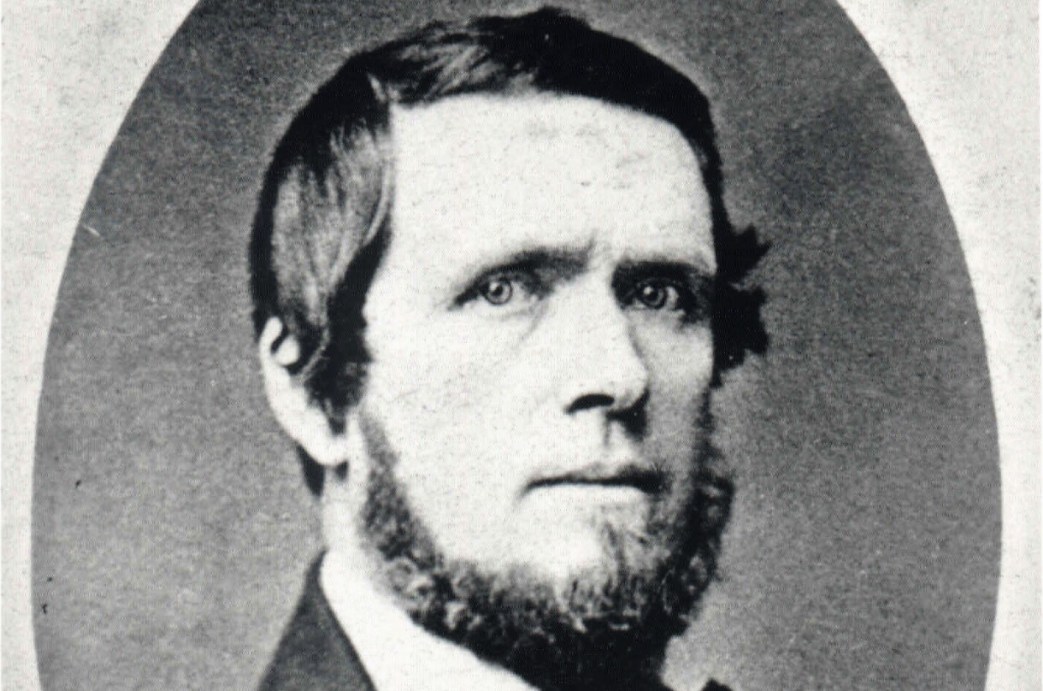

‘Wilhelm Weitling — A Forgotten Pioneer’ by Oliver Carlson from Young Worker. Vol. 2 No. 1. January, 1923.

ALL of us know more or less about such men as Marx, Engels, Bebel, Liebknecht, who were the founders and inaugurators of revolutionary socialism. We have become somewhat familiar with names like those of Saint Simon, Fourier, and Robert Owens as the leaders in the Utopian Socialist movement, but there are not many who are aware of the fact that Wilhelm Weitling was the first successful agitator among the workers of Europe during the years from 1830 to 1848. His conception, faulty tho it may have been, did much to arouse the workers in France, Switzerland, and Germany. It was largely thru his tireless efforts and incessant propaganda that the spirit of revolt was fanned into flame, which manifested itself thruout the whole of central Europe in the stormy years of 1848— 1850.

Wilhelm Weitling was born in Magdeburg, Germany, in 1808, the son of a poor soldier. From the earliest days of childhood he felt the cruel fangs of poverty. At an early age he was apprenticed to a tailor and he served under him until the age of 18, when he became a journeyman. Speaking of his rebellious spirit, he once said, “If I many times boil up in rage on account of the wretchedness of society, it is because I in my life have often had the opportunity of seeing misery near, and of feeling it, in part, myself; because I, as a boy, was raised in bitterest misery, so bitter, indeed, that I shudder to describe it.”

About the year 1828 he began his wanderings, and from that time was on the go until the days of his death. His mind was bent on reform. Already in 1830 he had written a number of articles, but which no one would publish. Gradually his ideas matured, and his agitation for Justice began to manifest itself.

Conditions at this period have been described as follows:

“We find ourselves in the midst of the troublous times between the July revolution of 1830 and the March revolution of 1848, between the two capital cities where life and thought of the two great European nations focus. The great French revolution and its immediate effects had become history. Its sacrificial fires had gone out in the temple of Vesta, but sparks were glowing still on household hearths before the Gods of Liberty, Equality, and Fraternity. Napoleon’s dramatic career had closed, but its influence was still mighty among the reconstructed states of Germany. A new generation had sprung up and a new code of ideas had been formulated. In France, constitutionmongers had given way to social reformers; in Germany, advocates of republic and unity seized the opportunity for political agitation. In France, new social theories were being discussed and social Utopias invented; in Germany, political emancipation from feudal conditions was the one united aim of the discontented classes. In both countries secret clubs and unions were formed for the propagation of the new ideas. While the Revolution of 1830 added to the list of liberties enjoyed by the French people, it caused the German people on the other hand to lose even the meagre liberties which they had.” Young Weitling went first to Leipzig, then to Vienna, where he worked for a while as a gardener, but conditions getting too hot for him to remain there, he went to Paris, which was at the time the center and hot-bed for all revolutionary movements. Arriving there 1837 he joined one of the secret organizations, known as the “Society of the Just.” Here the various socialistic theories were studied and discussed. That of Babet seemed to find the greatest number of followers.

It was not long ere Weitling became one of the most prominent members of this society, and its leading agitator. In 1838 he published his first book, “Mankind, As It Is, and As It Should Be.’ It seemed to take well, for within two years it had been translated into several languages. Then, in 1840, the organization sent Weitling to Switzerland with a view to spreading their propaganda and forming new branches of their organization. He went. There were a few revolutionary organizations in existence already, but now nearly extinct. Weitling, as a good tactician, joined these, and by a process of boring from within, soon gained adherents to his own views and formed a separate society. The following year he began publishing a monthly propaganda organ entitled, “The Cry for Help of the German Youth.” Its policy was expressed in the motto, “Against the interest of the few in so far as it works injury to the interest of all, and for the interest of all without excluding a single individual.” But the paper failed.

Not to be discouraged because of the difficulties encountered, he started another paper in 1843, “The Young Generation” which was confiscated by the authorities. His “Guarantees of Harmony and Freedom” was secretly published in December of that year. Meanwhile he was organizing everywhere possible. Soon there were branches in a great many places. The local and national authorities were greatly worried over the agitation, so Weitling was seized, his home searched, and masses of documents, literature, and correspondence taken. He was given six months imprisonment and banished from Switzerland for 5 years. Upon being taken across the border into Germany, he was at once held by the Baden authorities who shipped him to Magdeburg where he was held as a refugee from military service. Within a short time he was released, and proceeded to Hamburg. In August he went to London, England, where he was hailed as a martyr.

“He spoke at a meeting on the 22nd of September, at which the Communists of many land were present primarily for the purpose of greeting him. He closed his speech with the toast—’The Young Europe: may the democrats of all nations, casting away all jealousy and national antipathy of the past, unite in a brotherly phalanx for the destruction of tyranny and for the universal triumph of equality.’ In 1846 the Rhenische Jahrbucher speaking of this meeting said: “The proletariat of all nations begin under the banner of communistic democracy to fraternize.” Professor Adler considers this meeting the first in which the socialists of various countries came together in common and emphasized the cosmopolitan principles of socialism and says that it led to the founding of the International.”

It was shortly after this, in Brussels, where Weitling first met Marx and Engels who had fled to Belgium.

They had many long and animated discussions. Weitling was essentially a Utopian, and above all a believer in the principles of Christianity, which sought to harmonize with those of Communism. He turns to the Bible to establish his own theories, saying, “The premise of Voltaire and others was that religion must be destroyed in order to rescue mankind; but Lamenais, and before him many Christian reformers, as Thomas Munzer and others, showed that all democratic ideas are the outflow of Christian Religion, then, must not be destroyed but used for the rescuing of mankind. Christ is the prophet of freedom; His theories are the theories of freedom and love.”

In a letter to a friend he says, “I see in Marx nothing else than a good encyclopedia but no genius.” He sailed for the United States late 1847, but returned to Germany upon news of the revolution there in the following year.

The revolutionary movement collapsed, and Weitling, who did much good work during that time, was once more forced to leave the country in 1849, again coming to America. He formed a Laborers’ Union in New York city with the idea of supporting a communistic colony in Wisconsin. The scheme was actually put into operation, and “Communia,” as it was called, lasted for several years before it collapsed, but thru no fault of Weitling’s. Returning to New York he procured a position as a clerical worker, and from that time till his death was more or less inactive.

Altho he could never agree with the communistic principles as laid down by Marx and Engels, being more of a schemer and dreamer, still shortly before his decease became more reconciled to them and gave advice and aid to the members of the International, when its headquarters were transferred to New York. In fact, three days prior to his death, on January 22, 1871, he was the main speaker at a brotherhood fete of the English, French, and German sections of the International in New York.

Dawson says “Weitling may rightly be called the Father of German Communism.” Professor Clark speaks of him as “The most prominent socialist agitator which Germany produced prior to 1846, and when all the facts are known and rightly judged, perhaps the greatest single agitator, with the single exception of LaSalle.”

Engels refers to this “Social-Democratic tailor” already in 1846 as “The only German Socialist who has actually done anything.” Karl Marx too recognized his abilities, saying, “Concerning the educational condition or the educational ability of the German laborers in general, I am reminded of the gifted writings of Weitling, which often even surpass Proudhon, however impracticable they may be. Where could the bourgeoisie–their philosophers and learned writers taken together–show a work equal to Weitling’s Guarantees of Harmony and Freedom in relation to their political emancipation!… the jejune and feeble mediocrity of German political literature be compared with this incomparable and brilliant debut of the German working men.”

Weitling has been dead for more than half a century, and his name is now almost forgotten, but the seed he sowed is still bearing fruit-for the revolutionary movement of the working class no longer counts its adherents by the hundred or the thousand. Their number is legion.

Weitling is gone, but the Youth of today is bearing the banner that he unfurled so long ago. They have no false hopes nor illusions but their faith in the victory of the proletariat is as great as was his.

In closing this short sketch we can do no better than to quote from Vachel Lindsay’s poem “The Eagle That is Forgotten” for nowhere is it more applicable than to this sturdy pioneer of Communism.

They call on the names of a hundred high-valiant ones,

A hundred white eagles have risen, the sons of your sons

The zeal in their wings is a zeal that your dreaming began

The valor that wore out your soul in the service of man.

Sleep softly…eagle forgotten…under the stone.

Time has its way with you there, and the clay has its own.

Sleep on, O brave-hearted, O wise man that kindled the flame–

To live in mankind is far more than to live in a name,

To live in mankind, far, far more than to live in a name.

The Young Worker was produced by the Young Workers League of America beginning in 1922. The name of the Workers Party youth league followed the name of the adult party, changing to the Young Workers (Communist) League when the Workers Party became the Workers (Communist) Party in 1926. The journal was published monthly in Chicago and continued until 1927. Editors included Oliver Carlson, Martin Abern, Max Schachtman, Nat Kaplan, and Harry Gannes.

For PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/youngworker/v2n1-jan-1923-yw.pdf