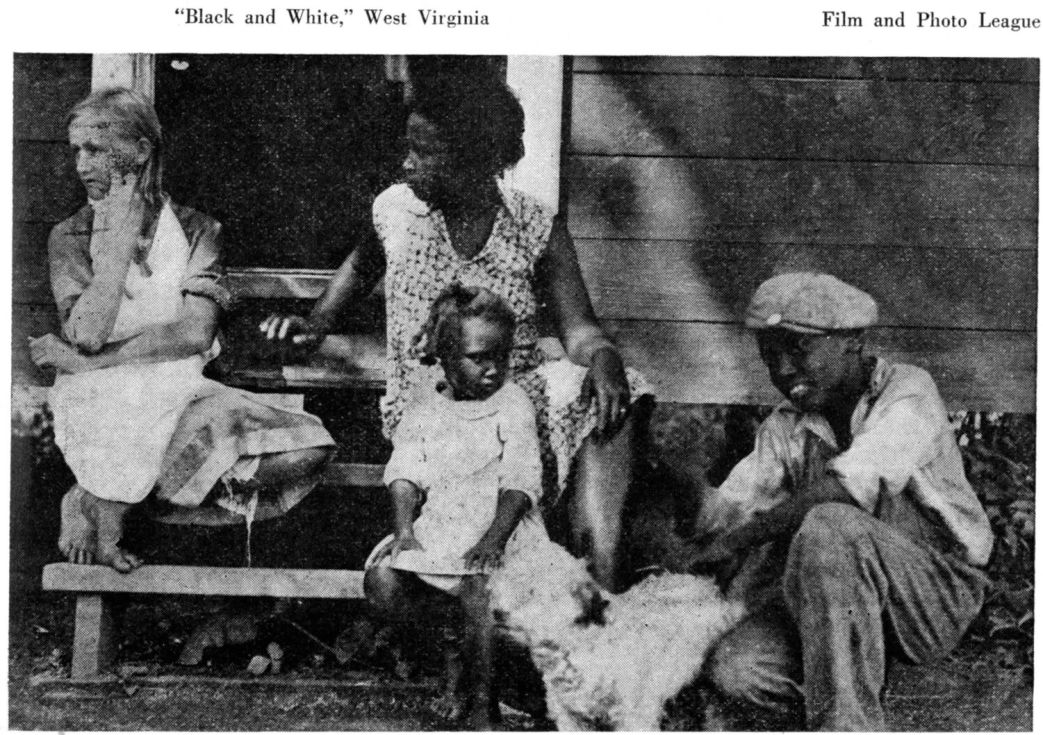

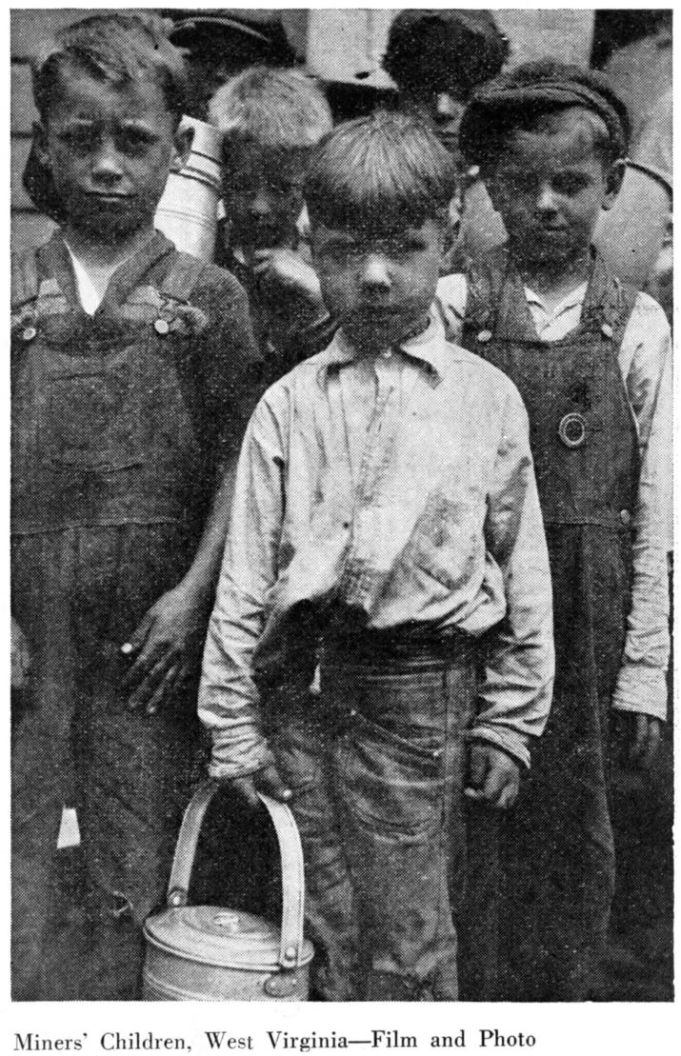

Wonderful story of bringing radical, inter-racial theater to the children of miners in the mountains of West Virginia during the summer of 1935.

‘Children’s Theatre on Tour’ by Ben Golden from New Theatre. Vol. 2 No. 10. October, 1935.

Slowly the little red truck winds its way up the hollow, carrying its cargo of young actors, who are about to give their first performance after three weeks of intensive training and rehearsal.

We are on our way to the little mining town of Black Hawk, West Virginia. When we arrive, we find some of the audience already waiting for us, while others are coming. A space has been cleared and staked off on the side of a hill. This is to be our stage; the audience is to sit below the hill on a level, plot of grass. Gradually the large space is filled with men, women and children, Negro and white. As they find places to sit, one of our group goes up to collect the five cents admission that is used to pay our travelling expenses. The sun falls behind the hill on which we are to perform, and darkness envelops the entire hollow. We have no spots, nor any other light for that matter, but the miners help us out by lending us some carbide lamps. Two of us station ourselves on each side of this natural stage and focus the lights on the actors.

In the distance we can see miners going to and from work, the carbide lamps stuck in front of their caps glimmering like tiny stars in the darkness.

The anti-war mass recitation is the first thing on the program. The audience is tense as the narrator tells of the horror of war, and actually thrills, when it hears the mass of young people in front of the narrator beginning to whisper at first, and then gradually becoming louder, to shout, “Black and white, unite to fight.”

The audience feels that here is something real, that these boys and girls are telling them the truth, that this is what war means, “maimed,” “crippled,” “hunger,” “misery,” “death,” “despair.” They wait tensely to the last line, when the actors point their fingers at them and say, with raised fists at the last word, “But the world shall be Ours!” Then the audience rises to its feet, cheering and applauding.

This was the first of nineteen scheduled performances in as many mining towns. These performances had been arranged for by Pioneer Youth, a non-partisan organization that works among the miners, chiefly the youth, of West Virginia, organizing them on a class struggle basis. Realizing the importance of dramatic work, Pioneer Youth had requested New Theatre League to assign one of its members to work on their staff this summer.

Immediately upon arrival, we had been confronted with the Negro question. The problem of course was to get a mixed group of children, Negro and white, to take part in the dramatic work. At first, we were unable to find any white kids who were willing to be in the same group with Negroes; where the children were willing, the parents objected. However, Pioneer Youth was determined that there would be no discrimination, and after a week of going from town to town, and speaking to children and parents, we were able to assemble a group of ten boys and girls, six white and four Negro, ranging from fourteen to eighteen.

Pioneer Youth has a camp on Coal River, to which it sends its members for a two-week stay. It was decided to send the dramatic group out there for three weeks, to give them the necessary training and to rehearse some plays.

The camp was ideal for the work. The group was away from chauvinist influences and we had time for rehearsals and training without interference. It also gave us an opportunity for many discussions on the Negro question, in which the reasons for the prevailing prejudices were pointed out.

The white members of the group soon realized for themselves that working with the Negroes did them no harm. More, they saw that they could learn a great deal from the Negroes, who were much better actors, and who excelled in imaginative interpretation and characterization.

Throughout my work with the group, I tried to get them to tell me what should be done, instead of my telling them what to do. We talked over a long time what kind of plays we should do. Since they were to write the plays themselves, each of them presented what he or she thought would be a good subject. Gaylord, a white boy, told of a large family he knew who were getting only $2.50 a week, and who lived on corn bread, mostly, and berries that they gathered on the hillside. “We ought to make up a play about that,” he said, “and maybe show them how to fight for more relief.” Roy Lee, a Negro boy, thought that the burning of the tipple at the Eskadale mine would be swell for a play. “We could show what it means to the miners to be thrown out of work through no fault of their own.” Louise, white, whose father was crippled for life by a slate fall and who has had to fight constantly for his compensation, wanted to dramatize a compensation case, and show how the company tried to cheat the miners out of what was rightfully theirs.

Out of all the suggestions two were chosen which dealt with the most urgent problems confronting the youth of West Virginia: a play against war, and a play showing how to organize a struggle for free textbooks. The latter question is a heated issue in the state: it is almost impossible for miners who are working only one or two days a week to buy school books for their children. This means that many children have been dropping out of school before their work is nearly completed.

For the anti-war play we used a mass recitation, arranged by the group, with my help, from a chant by Ernst Toller that had appeared in the New Masses last winter, and an anti-war poem written by a member of the Paterson New Theatre League group and published in Printer’s Voice, a trade union paper.

The school book play we built through improvisation, memorizing only the statistical material, such as figures on taxes and the cost of providing books for all the children in the state. Working through improvisations proved very fruitful for its training value, and kept the performance fresh and lively–we had many variations in the first few showings.

Our dress rehearsal was shown to an audience of farmers from the surrounding country–the ones from whom we bought our vegetables and supplies. About twenty-five came, some of them walking miles through the woods to get there. It was dark before they arrived to take their places on the benches we had made (planks across logs). The school book play went over big. Here was something the farmers knew and understood. When the scene of the Pioneer Youth was played, with the plans being made for organizing children and parents into a demonstration and going down to Charleston to demand free books from the Governor, the farmers applauded enthusiastically. During this scene the group draws up a petition and elects a committee to go out among the audience and collect signatures. This was done at every performance, and each time met with an eager response.

During the anti-war play comments were constant: “That’s right,” “You bet,” and one young man, “The only war I’ll ever fight in is when the poor fight against the rich!”

After the performance we spoke to the audience about our work, explaining why we had a mixed group, and pointing out the necessity of uniting Negro and white workers and farmers. We tried to involve the audience in this discussion, but none of them would talk. Some of the youngsters in the group took part, however, and told their experiences at camp in a mixed group.

Gaylord said, “In this fight for free textbooks we need the Negro children, because if we went to Charleston without them, they would say, “The Negro kids aren’t asking for books, why should you?’ and the same if the Negroes went down there alone.” Others showed how the Negroes like other workers were threatened by war, and how unity was needed in the fight against the bosses, that all this prejudice was a trick to keep them from fighting together for their needs.

After this performance we left camp, to begin our nineteen scheduled performances. Many interesting things happened during our travels. There was the town of Galaghar, where we were supposed to get the little Negro school for our performance. At the last minute, those in charge, without giving any explanation, wouldn’t open the school. All they said was “We are not allowed to open the school.” Where the pressure (if any) came from, we were unable to find out.

But undaunted, we led the audience into a Negro family’s back yard and gave our performance there. This Negro town cooperated one hundred percent, many people bringing chairs and other furniture for the audience to sit on.

Just as we were about to start, some of the audience noticed a group of people seated on their porches, ready to see the show. These who had paid their five cents admission, thought this was unfair. So the performance was held up while one woman brought pieces of wire and rope, which were tied across the yard. Another brought some sheets and hung them over the rope enclosing the actors. The people who had thought that they would see the show for nothing, promptly came down, bringing their chairs and admission fees.

That night also we spoke to the audience, telling them why we gave a play against war, pointing to Italy’s attack on Ethiopia, and foretelling what war would mean to the miners and their families. The audience applauded the plays and players, and many told of the need for such plays.

The Negro towns were the ones that received us with open arms. In the town of Whittikar, a Negro village of seventeen families, the audience had not gathered when we got there. The minister, angry at the tardiness of his flock, rang the church bell to call them–the entire town turned out and showed its approval by shouting and stamping feet.

Not all the towns received us in this way. The town of Mammouth resented the fact that we had a mixed group. When I spoke of the need for working class unity of Negro and white, some of the audience walked out. Those who remained received our plays in cold silence. The two Negro girls who always sang some spirituals between the two plays were laughed at, and left the stage without finishing their numbers. A member of the group who lived in this town withdrew the next day, and we had to break someone else into the part.

The summer’s work ended with a demonstration of 400 children and parents in Charleston on August 24. When the police refused the children a permit to march, they piled into the trucks that had brought them from the mining camps. After tacking their banners to the trucks, they wended their way slowly through the city, touching every spot through which they had intended to march, shouting their slogans and singing their songs.

At the Capitol, a committee went in to see the governor to speak and to present him with the nearly ten thousand signatures on the petitions. The rest of the demonstrators stood on the Capitol steps shouting the slogans that were used in the play, “Black and white, unite and fight, for free schoolbooks,” and, “One, two, three, four, what are we here for? Free textbooks, Yeah.”

The governor sidestepped the committee politely. His secretary explained at length how hard the governor had fought to get books for the children of West Virginia. The committee remained unimpressed. They knew that a previous committee that had gone to the governor to ask that part of a known two million dollar surplus in the State Treasury be used for school books, had been told, “This money must go to the bankers, to cut down the interest on the state debt.”

When they came out of the governor’s office, they told the rest what had happened. All of them then pledged to carry on the fight for free books. Dramatics was to play an important part in this fight as it did in helping to organize the demonstration.

From these sketchy notes, it can readily be seen what a field there is for theatre work among miners, steel workers, etc. Not only can the theatre provide entertainment for these people who, through poverty are denied almost every form of amusement and pleasure, but it can be a powerful force for organizing them to struggle for their own immediate needs.

Workers Theatre began in New York City in 1931 as the publication of The Workers Laboratory Theater collective, an agitprop group associated with Workers International Relief, becoming the League of Workers Theaters, section of the International Union of Revolutionary Theater of the Comintern. The rough production values of the first years were replaced by a color magazine as it became primarily associated with the New Theater. It contains a wealth of left cultural history and ideas. Published roughly monthly were Workers Theater from April 1931-July/Aug 1933, New Theater from Sept/Oct 1933-November 1937, New Theater and Film from April and March of 1937, (only two issues).

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/workers-theatre/v2n10-oct-1935-New-Theatre.pdf