A compelling figure to describe the early national policies of the Soviets. Moisei Rafes was a veteran and leading Bundist active in Ukraine. There he was a participant in the 1917 Revolutions and originally hostile to the Bolsheviks. He, like so many other Bundists, moved toward the Communist Party during the Civil War. He was a central figure in the majority split in the Bund that joined the C.P., and would fight with the Red Army where he became a commissar. After the war he worked for the Moscow Soviet and Comintern, leading its Far Eastern Bureau for a time and traveling to China to reorganize the C.P. there after the break with the Kuomintang in 1927. In the late 20s, he shifted gears and worked for Sovinko, the Soviet film agency, as art, and later, cinematography director. He also wrote histories of the Jewish workers’ movement. A victim of the Purges, he was arrested in 1938 and died in a labor camp, likely in 1942.

‘The U.S.S.R. and the National Question’ by Moisei Rafes from Communist International. Vol. 2 No. 9. March, 1925.

(On the Occasion of the Seventh Anniversary of the October Revolution)

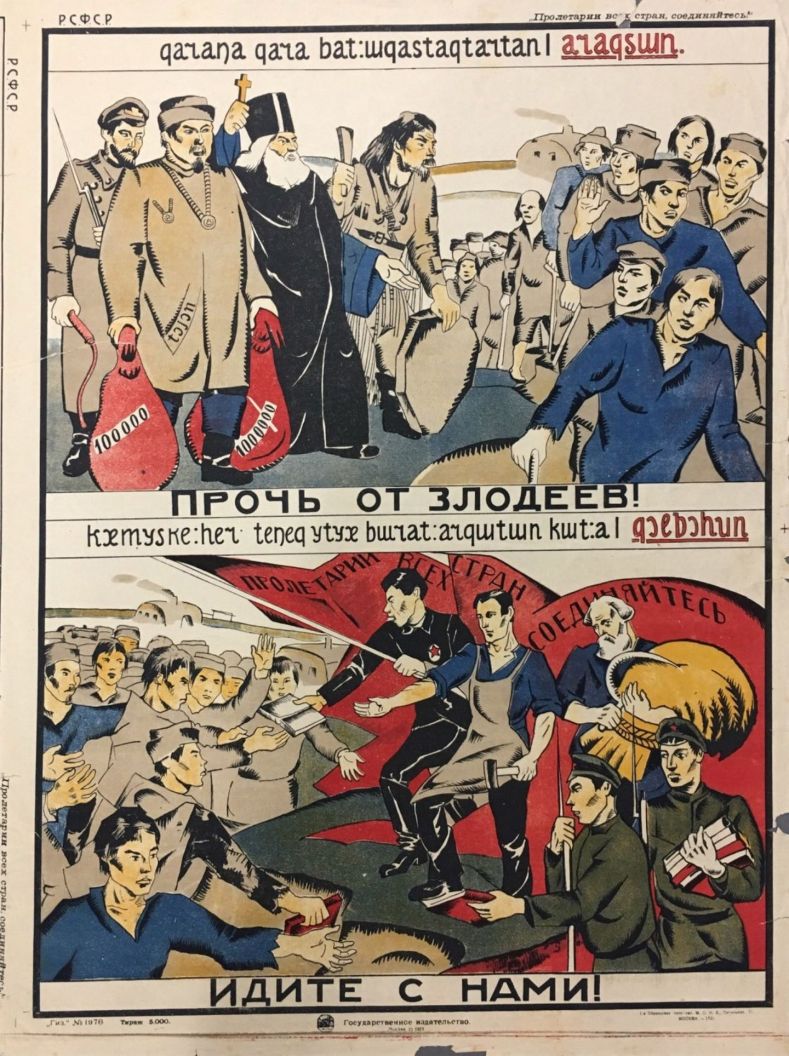

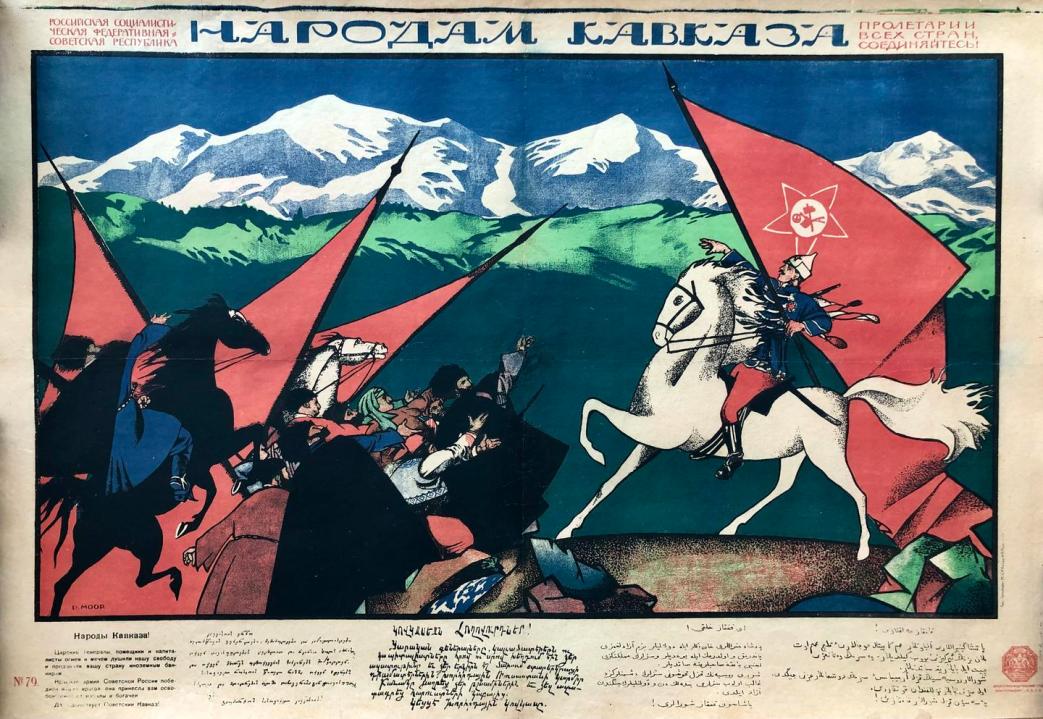

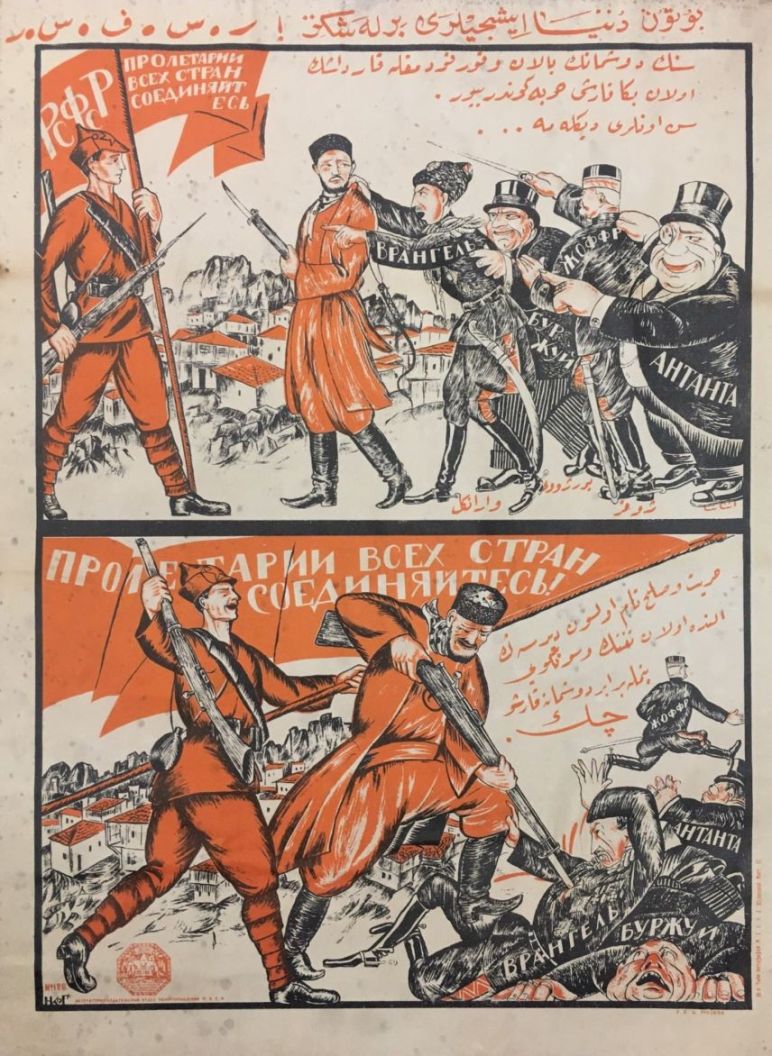

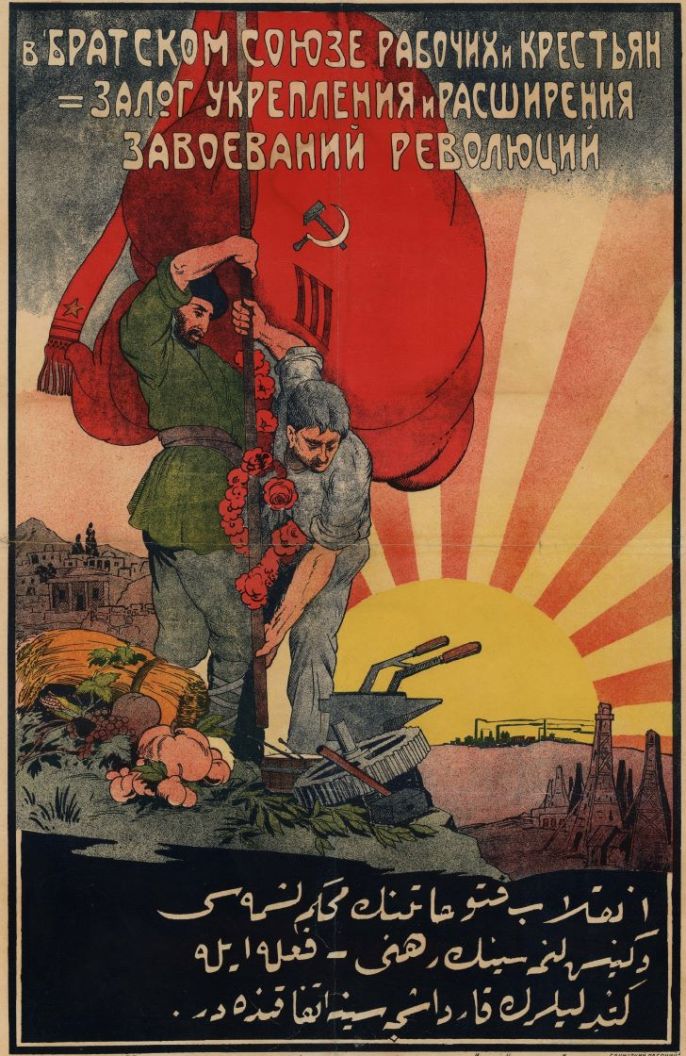

THE October Revolution imbibed from its leader, Comrade Lenin, a great loathing for all oppression, including national oppression. One of its tasks was to give the world a real sample of a revolutionary solution of the national question on the basis of the brotherly solidarity of the emancipated workers and peasants. This work is not yet quite accomplished, but we are justified in saying that the main problem has been solved.

I. The Period of Civil War.

The ruling nationality under the Czarist regime was the Great Russian. This nationality from which the ruling bureaucracy was recruited, constituted only 43.3 per cent. of the total population of the country.

Great Russians occupied the central part of the Empire. In the South, West, North and East, there were peoples who were subject to national oppression. Moreover, some of them had been forcibly included in the Czarist Empire, such as Ukrainians, White Russians, Poles, Jews, Tartars, Bashkirs, Karalians, Finns, Germans, Uzvecks, Turkomens, Tadzniks, Armenians, Georgians, Tcherkess, Les- ghis, Chubash, Votiaks, Burats, Kalmiks, and many others–in all about one hundred nationalities. In order to maintain its domination over these peoples and in order to give privileges to the ruling Great Russian bureaucracy, Czarism pursued a policy of forcible Russification towards these nationalities, and at the same time did its utmost to cause enmity among them. The mass of the Great Russians was contaminated with the same haughtiness and contempt for the “stranger” as the Czarist bureaucracy. The workers and peasants of the oppressed peoples were filled with hatred and distrust to Great Russians as a whole, instead of with the legitimate hatred to Great Russian landowner capitalists, and to the autocratic bureaucracy.

National oppression was one of the mainstays of the Czarist regime, just as for instance the domination of British capitalism over the colonies of the British Empire is the mainstay of its power in the country. Hence the Bolshevik regarded the fight for independence of the oppressed peoples as one of the means for the destruction of Czarist despotism. Already the first Congress of the Russian Social-Democratic Labour Party (the progenitor of the Russian Communist Party) recognised “the right to national self-determination.” This meant that the Bolsheviks did not respect the frontiers established by Czarism by means of annexation, and also that the Bolsheviks would support the oppressed nationalities’ fight for their independence. But at the same time “the Bolsheviks ” never tired of urging the workers of all the oppressed nationalities of Czarist Russia to unite in the fight against common enemies: Czarism and capitalism. “The Bolsheviks” urged the establishment of one revolutionary proletarian party to unite the workers of all nationalities.

The October Revolution, by destroying the foundation of bourgeois domination, put an end to the very possibility of national oppression, which is, of course, one of the forms of bourgeois exploitation.

The following principles were proclaimed in the decree of the Soviet of People’s Commissars of November 9th:

1. Equality and sovereignty of the peoples of Russia. 2. Their right to self-determination, including separation and establishment of an independent State. 3. Abolition of all and sundry national and national-religious privileges and limitations. 4. Free development of national minorities and ethnographical groups inhabiting Russian territory.

At the time of the October Revolution part of the former Russian Empire (Poland, Lithuania and Latvia) was occupied by German troops. German generals “self-determined” Poland. In the Ukraine, the urban and rural bourgeoisie and the kulaks of whom the Central Rada was composed, aimed at complete separation from Soviet Russia where proletarian dictatorship had been established. They proclaimed the independence of the Ukraine, but subsequently German and Austrian generals, who were invited by the Central Rada, “self-determined ” the Ukraine, too. They put Hetman Skoropadsky at the head of affairs and used all the wealth of the Ukraine for the rvitalisation of Austria and Germany, which were exhausted by the war. Here independence became occupation.

When at the end of 1918 revolution broke out in Germany, and the German and Austrian armies which occupied the Ukraine, Poland, Lithuania, Latvia and Esthonia disintegrated, civil war for the conquest of power broke out in all these countries. Wherever the proletariat, together with the poor peasantry was victorious, it established a new national soviet state and entered immediately into close relations with the first Soviet Republic–the R.S.F.S.R. This is how the Latvian, Ukrainian, Lithuanian-White-Russian Soviet Republics came into being. Each of these soviet republics would have been beaten separately by strong enemies therefore, the establishment of the Union of Soviet Republics was an absolute necessity.

In Poland, Finland and Latvia, victory in the civil war remained with the landowners, kulaks and the bourgeoisie.

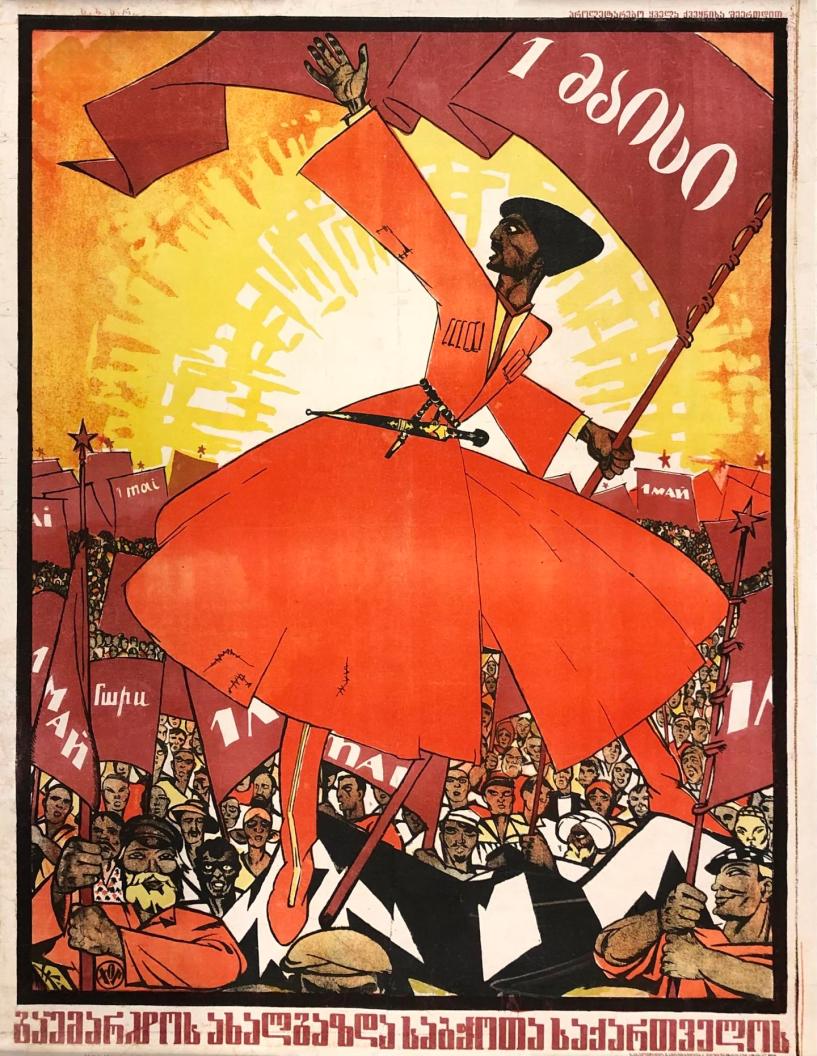

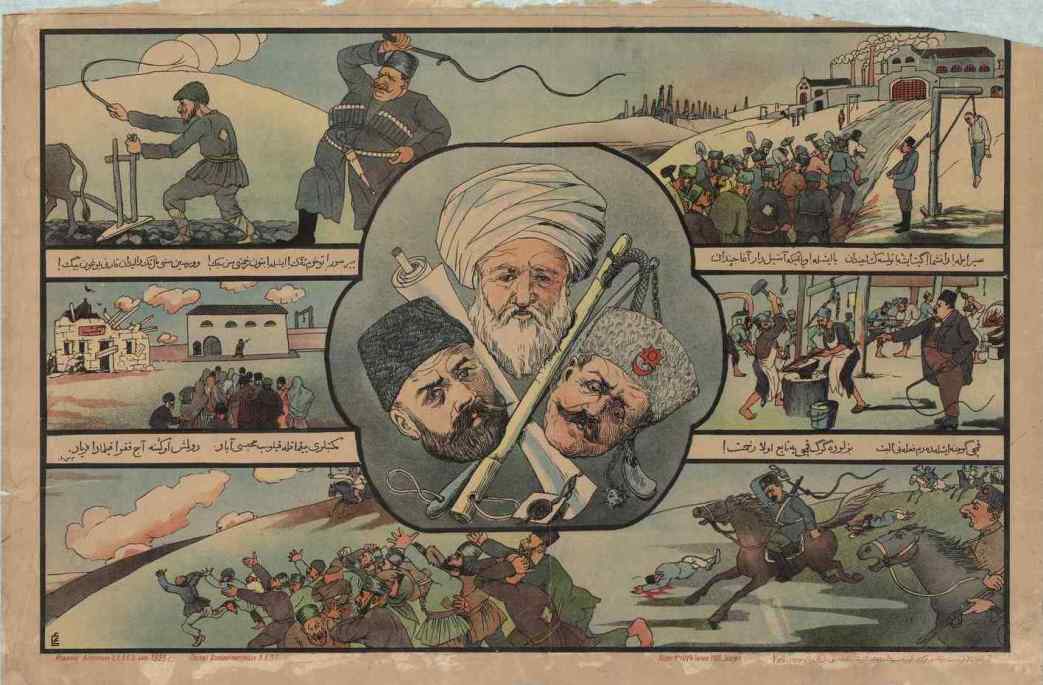

In the Caucasus, Georgian mensheviks, Armenian “Dashmaks “” (capitalist-democratic Party) and Tartar “Mussavatists” (feudal-capitalist party, the latter element predominating) severed from Russia because of their hatred of the Soviet Power, and established independent States: Georgia, Azerbeidjan and Armenia. They received support at first from German and subsequently from British capitalists who wanted to get possession of the Baku oil and the mineral wealth of the Southern Caucasus. The subsequent victory of the working class in these States strengthened their independence and welded them together into one, Trans-Caucasian Federation. At the same time the necessity for joint struggle against world capitalism and for joint efforts in building up of a Socialist order prompted the workers of Georgia, Armenia and Azerbeidjan to unite with the first and the strongest of all the Soviet republics–the R.S.F.S.R.

II. Independence and Unity.

In 1920, civil war came to an end. The Soviet Republic made peace with Finland, Latvia, Esthonia and Lithuania, and was the first to recognise their independence. In the be- ginning of 1921 peace was also signed with Poland in Riga on the strength of which, part of White Russia and of the Ukraine was added to Poland. At this juncture the energy of the organs of the Soviet power was concentrated on internal work–the consolidation and development of the emancipated peoples of the former Czarist empire which had formed themselves into a Soviet Federation. Already the programme of the Russian Communist Party adopted in 1919 at its Eighth Congress (9) contained distinct directions and instructions for the solution of the national question within the Soviet Federation.

It was stated in the programme: “a prominent place must be given to the policy of bringing together the proletarians and semi-proletarians of various nationalities for the joint revolutionary struggle for the overthrow of the landowners and the bourgeoisie. As a transition phase on the road to complete unity, the Party advocates the federative amalgamation of States organised on the Soviet basis…

“In any case the proletariat of the former oppressed nations must pay special consideration to the relics of national sentiment and must show great circumspection in the treatment of the workers of these formerly oppressed nationalities. It is this policy alone which will make it possible to create conditions conducive to the establishment of durable voluntary unity between the various national elements of the international proletariat, as shown by the successful experiment of amalgamating a number of national Soviet republics with Soviet Russia as the centre.”

The Tenth Congress of the R.C.P., which met in the beginning of 1921, immediately after the conclusion of civil war, summed up and put into a more concrete form the fundamental principles of our national policy:

“…an isolated existence of separate Soviet republics is unstable and not durable in view of the fact that their existence is endangered by the designs of the capitalist States. The common interests of the Soviet Republics, the re-establishment of the productive forces destroyed by the war, as well as the absolute necessity for the grain producing Soviet Republics to help non-grain producing republics, peremptorily demand the establishment of a Union of Soviet Republics as the only salvation from imperialist slavery and national oppression. The national Soviet Republics, having shaken off the yoke of “their own “their own” and of the foreign bourgeoisie can safeguard their existence and get the best of the united forces of imperialism, provided they establish a close State union. Otherwise they cannot be victorious…

“But the Federation cannot be durable and the results of Federation cannot be real unless it possesses the mutual confidence and the consent of all the countries forming part of it.

“This voluntary character of the Federation must be also maintained in future, for only a federation on these lines can become a transition phase towards the higher unity of the workers of the world within one big world amalgamation, the necessity of which is becoming more and more imperative.”

The foundation of national and international Soviet construction consists in independent and autonomous Soviet Republics amalgamated on the federative basis. The complete forms of federative amalgamation underwent changes during the last seven years, and changes are still taking place, for instance in Central Asia. But the basic thing existed from the very beginning and was dictated by the real interests of the workers.

The Soviet Republics are free from petty bourgeois narrow-mindedness, and give free play for the growing tendency towards centralisation, towards amalgamation of revolutionary forces and economic wealth. Five branches of Soviet work were at the wish of all the workers concentrated from the beginning in the hands of the united federation. They were: (1) the armed forces, (2) the international policy of the Soviet power (diplomacy), (3) foreign trade, (4) industry, transport post and telegraph, and (5) finance.

As to the first three branches, no doubt whatever could be entertained. Even the bourgeoisie was compelled during the years of the world war to have recourse to centralisation of military command. One of the reasons for the Entente victory over the German coalition was the fact that it was able to overcome the independence of French, British, American and Belgian military forces, and to form them into a united front which could be brought into action at the order of one supreme military command. This is all the more necessary for the proletariat and its Red Army.

Moreover, the interests of the Federated Soviet Republics are such that they can be safely left in the hands of their federation in the face of world capitalism. And as for foreign policy, Soviet red diplomacy can only be successful, monopoly of foreign trade can only be maintained and victorious on this front, if the Soviet Republics are able to oppose world capitalism by which they are surrounded not separately, but as one united state organisation.

Industrial amalgamation is a more complicated affair. This question has been solved in the following manner: some enterprises have been left under the administration of local Soviets, and hence of the separate Soviet Republics, while others which were of federative importance, are under the administration of the Supreme Council of National Economy. At the same time common economic activities are determined by the organs of the Union, and are obligatory for all Soviet Republics. Railways, the post and telegraph services, are amalgamated in the Peoples’ Commissariats of the Union.

The reason for this is obvious. The nationalised industries are the most important centres of proletarian dictatorship which must meet the joint attack of both the home and foreign bourgeoisie. The proper administration of the oil industry in the Baku district or of the coal industry in the Donetz Basin or the development and preservation of railway communication–all this could not be dealt with alone by the republic containing the oil fields, mines or railway lines. Moreover, these enterprises are not for the benefit of one district, but for the working population of the entire Federation. This necessitates a uniform policy and one common master over all the wealth which the proletariat has taken over from the bourgeoisie. The same applies to finance which is the mainstay of the work of the Federation on the economic field. It would be a petty bourgeois reactionary relapse if different money systems were set up within the Federation. This would mean that we would not have our chervonetz, and such a breach in our front would form a loophole for the enemy.

The harmonious relations between the Federation and the various republics which form part of it, which is here described, has not come into being all at once. It crystallised only in the seventh year of the Soviet Power, taking the form of “the Union of Socialist Soviet Republics.” The Union is composed of two Federations: (1) the R.S.F.S.R., and (2) the Trans-Caucasian, Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (consisting of three republics: the Georgian, Armenian and Azerbaidjan Republics) and separate national republics, (3) the White Russian Republic, and (4) the Ukrainian Republic. The R.S.F.S.R. itself consists of eleven republics and ten autonomous regions.

The constitution of the “Union ” adopted July 6th, 1923, defined very clearly the organisation and construction of the joint congresses of the Central Executive Committee and the Soviet of People’s Commissars of the Union, while the session of the Central Executive Committee held in October endorsed the regulations concerning every one of the united People’s Commissariats. To promote a still greater rapprochement between the peoples, a Nationalities’ Soviet has been attached to the Central Executive Committee of the Union, consisting of representatives of all national republics and regions. But this is not all, more reorganisation is taking place at present in the republics of Central Asia.

Until recently proletarian revolution in Central Asia in its fullest development reached the gates of Bokhara and Khorezm. In these countries the power of Emir and Khan was overthrown, but the republics which sprang up as a result of this revolution were not placed on a Socialist basis, which demands that voting power should be restricted to the working class element, but merely assumed the form of national republics friendly to us.

The Turkestan Soviet Republic had among its population many nationalities: Uzbecs, Khirgizs, Tadjis, Turkomen, etc. These same nationalities form also part of the population of Bokhara and Khorezm. These peoples collected in one republic could not exercise the right of self-determination and establish autonomous administration suitable to each of them. National frictions took place.

At present united republics are in the course of formation–the Turkoman Republic (Turkmanistan) and the Uzbec Republic (Uzbecestan), Samarkand being the capital, and two autonomous republics: the Tadjkik Republic, which will form part of the Uzbec Republic, and the Kara Khirgiz Republic, which will form part of the R.S.F.S.R. This reorganisation aims at bringing Party and Soviet organisations nearer to the lower strata of the emancipated Eastern peoples, and at building up governmental power on the principle of national self-determination. This reorganisation will be of an enormous international significance: Eastern peoples living beyond the cordon of Soviet Republics will be able to realise the true nature of the liberation policy of the Soviet Government, which is alien to any form of imperialism and is taking up boldly and wholeheartedly the task of bringing about the national regeneration of the Eastern peoples who not so long ago were the object of Czarist exploitation.

Hitherto we have dealt with nationalities concentrated in one single territory. But this alone does not solve the national question. In the towns we frequently meet tens of thousands of citizens of a different nationality from the population of the respective district. Thus Tartars do not live in the Tartar or Crimean Republics, but are scattered throughout cities far remote from these republics. The same applies to Letts, Poles and Jews. To satisfy the cultural needs of such national minorities, special national minorities’ departments are being formed in the people’s Education Commissariat, as well as in the gubernia People’s Education Department.

III. After the Twelfth Congress.

The Twelfth Congress of our Party, which was held in April, 1923, having summed up the Party and Soviet work performed during two years of peaceful construction under conditions created by the New Economic Policy, turned its attention again to the national question, and confirmed the existence of a number of abnormal and injurious phenomena.

The congress dealt in one of its resolutions with a number of perils which are a relic of the old social order with its nationalist oppression.

1. Relics of autocratic Russian chauvinism rooted in our state institutions and demonstrated in a superciliously, contemptuous and heartless bureaucratic attitude on the part of Russian Soviet officials towards the needs and requirements of the national republics.

2. The danger of disunion between town and countryside in the national republics, arising from the fact that the Great Russian element which predominates in the towns, creates the Soviet apparatus which cannot satisfy and be within the reach of peasant Ukrainians, White Russians, Tartars and Bashkirs.

3. The economic backwardness of the national republics and their lack of factories and workshops where the proletariat of the native population of the said republics could concentrate.

4. The existence of national frictions between the peoples forming part of the population of one and the same republic, such frictions being encouraged by national chauvinism (Georgian, Tartar and Uzbec).

5. The low level of cultural educational work in the republics resulting from the insufficient grants made for this purpose by the Centre.

The greatest danger is in disunion between the proltariat and the peasantry. The majority of the factory and workshop proletariat is concentrated in the great Russian gubernias. The White Russian Ukrainian Tartar and Bashkir peoples who were oppressed by Czarism are mostly composed of peasants. By establishing close contact between the great Russian proletariat and the peasantry of all the peoples of the Union, we would abolish the very possibility of national frictions within the Soviet Union. If this is to be achieved, the Soviet apparatus must be brought nearer to the peasantry, the cultural level of the latter must be raised and their distrust which was fostered by years of national persecution, must be overcome.

The Twelfth Party Congress proposed a number of measures to this effect. We enumerate the most important of them:

(1) The Republics must be given comprehensive financial and also budget rights, in order to enable them to show their own initiative in State, administrative, cultural and economic activities.

(2) The organs of the national republics and regions must be pre-eminently composed of local people, knowing the language, the habits and customs of the peoples in question.

(3) Special legislation must be introduced, guaranteeing the use of the native language in national regions.

(4) An impetus must be given to educational work in the Red Army, in the direction of instilling into other Red Army men ideas of brotherhood and solidarity between all the people of our Union. Practical measures must be taken in connection with the organisation of national army units, to guarantee that everything is done for the adequate defence of the republic.

A great deal has already been done by Soviet and Party organisations in the direction of carrying out the decisions of the Congress during the eighteen months which have elapsed since the Twelfth Congress of the Party. The transition from Russian to the native languages in the Soviet apparatus demands serious preliminary work in connection with the formation of a big cadre of Soviet and Party workers drawn from the native populations, or at least from circles familiar to the various vernaculars.

The opening of new specialised schools for this purpose will give an impetus to work on this field. Workers of Soviet institutions must learn local languages within a certain limit of time. In the Transcaucasian Federation, a decree re languages has been promulgated.

The growth of the national press, which has been noticeable during the last twelve months, and which had the full support of the Central Committee of the Party is very significant. In the national republics the countryside can only be reached through the national press. Now this is fully recognised, and matters are moving in the right direction.

Much has also been done with respect to the Red Army.

In the national regions (in the Tartar, Turkestan and Trans-Caucasian Republics) the Red Army unit is for the masses the only organ which, as far as they are concerned, embodies the central power of the union. During the revolution, close contact has been established between the peoples of the Union and their Red Army. This contact must be made even closer than before, it must be fostered by every possible means. With relation to this the existence within the Red Army of national units quartered in their own republics, would be of the greatest importance. Long ago steps were taken in this direction. In the Caucasus there have been already for several years separate Georgian, Armenian and Tartar units, each one of them quartered in its respective republic.

At present, this question has been raised in all the national republics, but the main difficulty lies in the lack of a well-trained national staff of officers. To remedy this evil national military schools, with a normal programme are being opened. Three years hence these schools will be able to turn out thousands of officers able to take command of Ukrainian, Tartar, Bashkir, Armenian, Georgian, Uzbec and Turkomen Red Army units.

Another important phenomenon which deserves mention is the strong desire of the working class and peasant youth of the peoples of the East to enter the ranks of the Red Army. Under the old regime, these elements never did any military service and mutinied when the Czar made an attempt in 1916 to force these peoples into the ranks of the Czarist army. We refer to the Uzbecs, Kirghizs, Turkomens and Tagzhiks, of Turkestan and Bokhara. At present we have a Bokhara Red Army constituted on the same basis as the Red Army of the entire union. Schools have been organised in Tashkent on a voluntary basis, and hundreds of revolutionary young workers and peasants, more than half of them non-party, have flocked to these schools.

A new Red Army is being formed in the East of the Eastern peoples who, hitherto served as a imperialist weapon for the suppression of the revolutionary movement in Europe, and for purposes of annexation (the Black African troops used for the occupation of the Ruhr). This phenomenon is of historical world importance and is a sign that the Soviet Revolution has achieved enormous successes among the masses in the East.

We have already pointed out those measures of the Soviet Government concerning the solution of the national question which are of a special nature. But the chief method to liquidate all the relics of the old times is the extension of Soviet and Party work and consolidation of the Soviet Power among the non-Russian peoples of our Union. Every success in agriculture, in the handicrafts and big industries in the national republics and regions, every step towards the raising of the cultural level of the working population of the national republics, every party meeting, every school and newspaper, and finally the presence of the workers and peasants of the non-Russian peoples in the ranks of the Russian Communist Party and of the Russian Young Communist League–all this combined consolidates the workers’ power among these peoples and gets new recruits for the proletarian revolution. With the growth of Soviet power grows and develops the Union of Peoples in the Soviet Republic.

The ECCI published the magazine ‘Communist International’ edited by Zinoviev and Karl Radek from 1919 until 1926 irregularly in German, French, Russian, and English. Restarting in 1927 until 1934. Unlike, Inprecorr, CI contained long-form articles by the leading figures of the International as well as proceedings, statements, and notices of the Comintern. No complete run of Communist International is available in English. Both were largely published outside of Soviet territory, with Communist International printed in London, to facilitate distribution and both were major contributors to the Communist press in the U.S. Communist International and Inprecorr are an invaluable English-language source on the history of the Communist International and its sections.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/ci/new_series/v02-n09-1925-new-series-CI-riaz-orig.pdf