Never published in their lifetime, what we now know as ‘The German Ideology,’ originally written to be a serial settling accounts with the Young Hegelians and other current philosophies, was rescued by the Marx-Engels-Lenin Institute from their notebooks and first published in 1932. The text below was translated by Sidney Hook from the German of the first edition of the Gesamtausgabe, and is, as was Marx’s wont, a feast for thought.

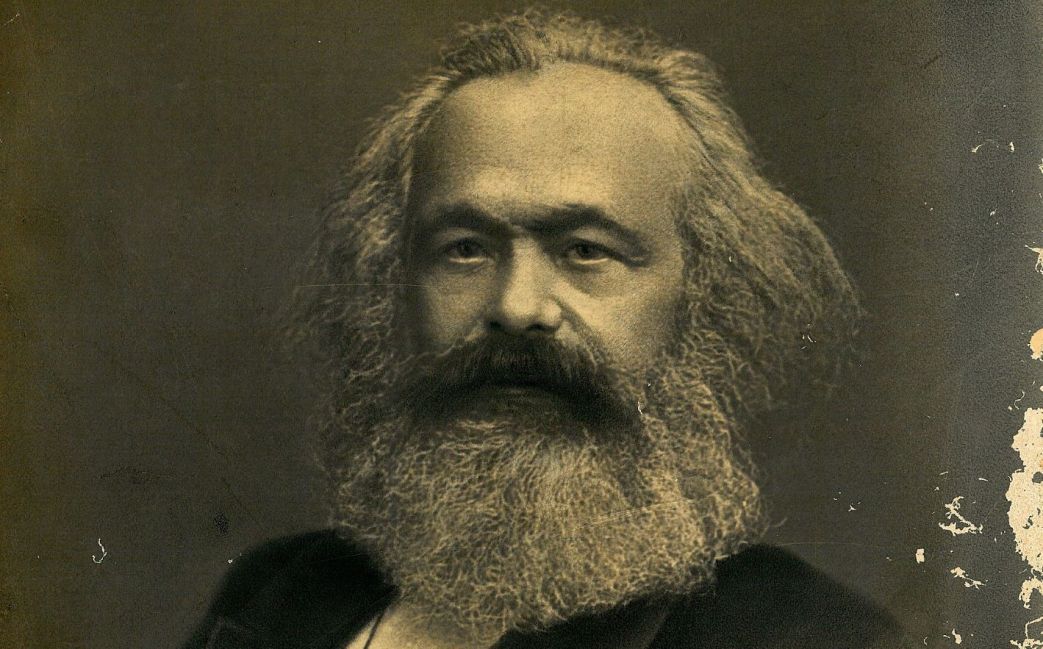

‘On Bentham and the Principle of Utility’ (1846) by Karl Marx from Socialist Review. Vol. 5 No. 1. March, 1936.

THE philosophy which preaches self- enjoyment is in Europe as old as the enjoyment is in Europe as old as the Cyrenaic school. Just as the Greeks in ancient times, so the French in modern times are the matadors of this philosophy, and indeed for the very same reasons–their temperament and their society give them above all others the capacity of enjoyment. The philosophy of pleasure was never anything else but the clever language of certain pleasure–privileged social classes. The form and content of their pleasures were continuously conditioned by the entire complex of the rest of society, and carried the marks of all its contradictions. But it was when this philosophy pretended to have a general validity and proclaimed itself as the philosophy of life of society as a whole that it degenerated into pure phrases. It sank to miserable moralizing, to sophistical rationalization of existing society-and even transformed it self into its opposite by declaring the involuntary asceticism [of the proletariat–S.H] to be a kind of pleasure.

The philosophy of pleasure emerged in modern times with the decline of feudalism and the transformation of the feudal landed nobility into the lusty pleasure loving and extravagant court nobility of the absolute monarchy. Among the nobility it still took the form primarily of an immediate, naive philosophy of life which had its expression in memoirs, poems and novels. It became a real philosophy only at the hands of several literary representatives of the bourgeoisie who, on the one hand, shared the education and mode of life of the court nobility and, on the other, subscribed to the more general outlook upon affairs of the bourgeoisie–an outlook rooted in the more general conditions of existence of the bourgeoisie. These writers were therefore accepted by both classes although from quite different points of view. Among the nobility, the language of pleasure was understood to be restricted to the confines of the first estate and its conditions of life; by the bourgeoisie, it was generalized and applied to all individuals considered in abstraction from their actual conditions of life so that the theory of pleasure became transformed into a stale and hypocritical sermonizing. As the further course of development overthrew the nobility and brought the bourgeoisie in- to open conflict with the proletariat, the nobility became devoutly religieuse and the bourgeoisie solemnly moral and strict in its theories in its theories…although the nobility in its practice did not in the least renounce pleasure while the bourgeoisie even made of pleasure an official economic category–luxury.

The connection between the pleasure-experiences of individuals at any time and the class relations of their time as well as the conditions of production and communication which produce the class relations within which individuals live, the limitation of all traditional pleasures which do not flow from real life activity of the individual, the connection between every philosophy of pleasure and the political pleasure at hand, and the hypocrisy of every philosophy of pleasure which presumes to generalize for all individuals regardless of their differences–all of this naturally could not be discovered until the conditions of production and communication of the traditional world had been criticized and the opposition between the bourgeois view of life and the proletarian socialist and communist point of view created. Therewith all morality-whether it be the morality of asceticism or that of the philosophy of pleasure was proved to be bankrupt.

***

To what extent the theory of mutual exploitation which Bentham, already at the beginning of this century, developed to the point of boredom can be regarded as a phase of the previous one, has been demonstrated by Hegel in the Phenomenologie. Compare the chapter on “The Struggle of the Enlightenment with Superstition” in which the theory of utility is presented as the final result of the enlightenment. The apparent absurdity which dissolves all the manifold relations of human beings to each other in the one relation of utility–this apparent metaphysical abstraction proceeds from the fact that within modern bourgeois society all relations are subsumed under the one abstract money and business relation. This theory arose with Hobbes and Locke in the period of the first and second English revolutions, the first blows by which the bourgeoisie conquered political power; it received its true content among the physiocrats who were the first to systematize economics. Already in Helvetius and Holbach we find an idealization of this doctrine which corresponded completely to the oppositional point of view of the French bourgeoisie before the revolution. In Holbach, all individual activity based on reciprocal response, e.g., speaking, loving, etc., is represented as relationships of utility and use (Nuetzlichkeits-und Benutzungs-verhaeltnisse). The real relations which are here presupposed are therefore speaking and loving, determinate behaviour forms of determinate properties of individuals. These relations are now not to have their own characteristic significance but are to be interpreted as expressions and manifestations of a third artificially introduced relation,–the relation of utility. This circumlocutory distortion ceases to be senseless and arbitrary as soon as the individual relations mentioned no longer appear as valid expressions of self-activity but as disguises–by no means of the category of use–but of a third genuine end and relation which goes by the name of utility-relation. The linguistic masquerade has a meaning only when it is the unconscious or conscious expression of a real masquerade. In this case the utility relation has a quite definite meaning, i.e., I can only serve myself insofar as I deprive others of something exploitation de l’homme par l’homme). Further, in this case, the utility which I derive out of a relationship is quite foreign to it. As we saw above in discussing the power or capacity to do anything, something is demanded of it which is a foreign product, a relation determined by social conditions—and this is the utility relation. And this is precisely the case for the bourgeois. Only one relation is intrinsically valid for him–the relation of exploitation; all other relations are valid only insofar as they can be subsumed under this relation. And even when relations appear which cannot be directly classified as one of exploitation, he at the very least does so in his illusions. The material expression of this utility is money, the measure of value of all things, human beings and social relations. Of course one can see at a glance that I cannot by reflection or will abstract the category of “usefulness” out of the real relationships to others in which I stand, and then presume to present these relationships as if they were the real expression of a self-evolving category which is itself derived from them. To proceed in this way is completely speculative. In the same fashion, and with the same justification, Hegel presented all relations as relations of Objective Mind. Holbach’s theory is the historically justified philosophical illusion of the rising French bourgeoisie whose lust for exploitation can still be interpreted as the desire to assure the full development of the individual in a social intercourse liberated from the old feudal bonds. Liberation from the point of the bourgeoisie–competition–was the only possible way during the eighteenth century to open up to the individual a new career for freer development. The theoretical proclamation of this consciousness which corresponded to bourgeois practice, the consciousness of mutual exploitation as the general relation of all individuals to one another, was a daring and outspoken sign of progress, a secular enlightenment in relation to the political, patriarchical, religious and sentimental embellishments of exploitation under feudalism; embellishments which were appropriate to the existing form of exploitation and were systematized by the literary representatives of absolute monarchy….

The different phases in the progress of the theory of utility and exploitation hang intimately together with the different epochs of bourgeois development. Its real content in Helvetius and Holbach never amounted to much more than a transcription of the manner of life of the literary man in the time of absolute monarchy. They expressed not the facts but rather the wish to reduce all relations to the relation of exploitation and to explain social intercourse out of material needs and the methods of gratifying them. But the problem was set. Hobbes and Locke had before their eyes not only the early development of the Dutch bourgeoisie (both lived for a while in Holland) but the first political actions by which the English bourgeoisie burst their local and provincial fetters and achieved a relatively developed manufacture, shipping and colonization: especially Locke who wrote at the period of English economy which witnessed the rise of the joint stock company, the Bank of England, and English naval supremacy. For both of them, particularly Locke, the theory of exploitation is filled with an immediate economic content. Helvetius and Holbach had before them in addition to English theory and the development of the Dutch and English bourgeoisie, the experiences of the French bourgeoisie still fighting for its right to free development. The universal commercial spirit of the eighteenth century had gripped all the classes in France in the form of speculation. The financial embarrassment of the government and the debates to which it gave rise over taxation concerned at that time the whole of France. To which must be added that Paris in the eighteenth century was the only world city, the only city in which personal inter- course between individuals of all nations took place. These premises, together with the universal character of the French, gave the theories of Helvetius and Holbach their characteristic, generalized color but deprived them at the same time of that which was still present among the English–its positive economic content. A theory which among the English was a simple observation of fact became among the French a philosophical system. As found in Helvetius and Holbach, the theory is universal but robbed of positive content and essentially lacking the rich fullness of meaning discovered only in Bentham and Mill. The former epitomize the fighting, the still undeveloped bourgeoisie; the latter, the ruling, developed bourgeoisie. The positive content of the theory of exploitation, neglected by Helvetius and Holbach, was developed and systematized by the physiocrats. But since they took as their point of departure the undeveloped economic relations of France in which feudal landed property still had great importance, they remained limited by their feudal conception and declared landed property and agricultural labor to be the productive forces which conditioned the whole organization of society. Further development of the theory of exploitation took place through Godwin, but more especially through Bentham who more and more assimilated into his system the economic content which the French neglected. Godwin’s Political Justice was written during the time of the French terror, the chief works of Bentham during and since the French revolution and the development of large industry in England. The complete unification of the theory of utility with political economy is to be found finally in Mill.

Political economy which earlier had been cultivated either by men of finance, bankers, and merchants, that is to say, by people who had some immediate contact with economic relations or by men with general culture like Hobbes, Locke and Hume for whom it had significance as a branch of encyclopedic knowledge–political economy was first elevated to a special science by the physiocrats.

Since their time it has been treated like one. As a special technical science it absorbed into itself other relations, political, juristic, etc., insofar as it reduced these relations to political ones. It regarded, however, this subsumption of all relations to itself as valid for only one aspect of these relations and acknowledged that they possessed some significance independently of economics. The complete subsumption of all existing relations under the utility relation, the unconditioned elevation of this utility relation to the sole content of all the rest, is to be found in Bentham, [for whom] after the French revolution and the development of large industry, the bourgeoisie steps on the scene no longer as a mere class among others but as a class whose conditions of existence are the conditions of existence for the whole of society.

After the sentimental and moralistic paraphrases which among the French constituted the entire content of the utility theory had been exhausted, the only thing that remained for the development of this theory was the question: How were individuals and relationships to be used or exploited? The answer to this question in the meantime had been given by political economy. The only possible progress therefore lay in assimilating the content of political economy. It had already been proclaimed in economic theory that independently of the will of the individual the primary relationships of exploitation were determined through production as a whole and were found ready to hand by individuals. There remained therefore for the theory of utility no other field save speculation concerning the position of the individual to the fundamental relations, the private-exploitation of the given world by the particular individual.

And on this point Bentham and his school delivered themselves of lengthy moral disquisitions. The whole criticism of the existing world by the utility theory was therewith restricted to a narrow field of vision. Limited by the presuppositions of the bourgeoisie, there remained for criticism only those relations which had been inherited from an earlier period and which stood in the way of the development of the bourgeoisie. To be sure, the theory of utility developed the conception that the whole complex of existing relations was bound up with economics but it did so in a partial and narrow way. From the very outset the utility theory had the character of a theory of general or public utility [utilitarianism]. This character only became significant with the assimilation of economic relation into the theory, particularly the division of labor and exchange. In the division of labor, the private activity of the individual becomes a common utility; the common utility of Bentham reduces itself to the same common utility observable in general in competition. Through the introduction of economic relations like ground rent, profit and wage labor, the definite relations of exploitation of the different classes were likewise introduced, for the kind of exploitation is dependent upon the position in life of the exploiters. Up to this point, the utility theory could tie up with definite social facts; its further divagations into the kinds and arts of exploitation peter out into copy book maxims. Its economic content gradually transformed the utility theory into a pure apologia for existing affairs, into the proof that under existing conditions the present relations of men to each other are the most advantageous and commonly useful. All modern political economy has this character.

Translated by Sidney Hook from die deutche Ideologie, Marx-Engels, Gesamtausgabe, Abt. 1, Bd 5; pp. 396-7, 387-392.

Socialist Review began as American Socialist Quarterly in 1934. The name changed to Socialist Review in September 1937. The journal reflected Norman Thomas’ supporters “Militant” tendency of the ‘center’ leadership. Beginning in 1936, there were also Fourth Internationalists lead by James P. Cannon as well as the right-wing tendency around the New Leader magazine also contributing. The articles reflect these ideological divisions, and for a time, the journal hosted important debates. The magazine continued as the SP official organ through the 1940s.

For a PDF of the full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/socialist-review/v05-n01-march-1936-soc-rev.pdf