An excellent piece from Budish on the demobilizing politics of lobbying, still the predominate method of ‘struggle’ engaged in by the labor movement.

‘The Strategy of Disintegration: Trade Unionism by Lobbying’ by J.M. Budish from Labor Age. Vol. 18 No. 1. January, 1929.

It is impossible to discover any enthusiasm for the last convention of the American Federation of Labor. Old timers who attended practically every convention of the Federation cannot conceal a certain feeling of disappointment. Not that there was any serious disagreement on policies at the New Orleans Convention. On the contrary, the delegates remember few A.F. of L. conventions at which things ran so smoothly and apparently so harmoniously. With minor exceptions the convention made all its decisions by unanimous vote and practically without any discussion. This total unanimity is even more surprising when the questions under consideration are so extremely perplexing.

To mention only the most important trade union problems affecting the progress and the very life of every labor organization. With insignificant exceptions every International Union has been marking time or losing ground. Mechanization of industry has made unprecedented strides. Men are continuously displaced by machinery. The human scrap heap of workers, deprived of their last drop of vitality by the acceleration of the rapidly rotating machine, is growing to be a serious menace to all Union standards of living and working conditions. The injunction reduces the workers to second-rate citizenship and in many cases imposes upon them, literally, industrial serfdom. Company unionism and welfare capitalism have been developed by open shop Big Business and Big Finance as powerful weapons to corrupt the workers’ mentality, control their minds and robotize them unto the level of the Mechanical Man. The Bar Association is promoting a plan which threatens to put the unions under the continuous tutelage, supervision and control of the courts by making the courts the ultimate arbiters in the interpretation and enforcement of every trade agreement, for there is practically no collective agreement without some provisions for conciliation and arbitration. The same plan would make all strike action by any trade union wait upon the preliminary investigation and report of some semi-judicial tribunal.

Two committees had these problems before them: the Committee on the Executive Council’s Report and the Committee on Resolutions. But the report of the first committee lasted only a little over an hour. And the report of the Committee on Resolutions would not have taken much more time if it were not for the flare up on the Brookwood and Dewey questions in which the ever-watchful eye of that vigilant guardian of 100 per cent Civic-Federation-Americanism detected something suspiciously akin to new social order theories.

How then is the ready, almost mechanical unanimity that prevailed at the New Orleans convention to be explained? Is it really possible that the report submitted by the Executive Council was of such flawless perfection that there was no place left for any further consideration? Or may it be that A.F. of L. trade unionism has become so fixed, so much a mere question of “economic statemanship” and “intelligent strategy” that it has become bad form to take up controversial questions, thus leaving to the Convention the part of a mere formal function, perhaps necessary but not very helpful and, in any case, entirely uninspiring? An insight into the present A.F. of L. trade union philosophy may supply the answer.

History is a continuous process. And still as the process of slow accumulation of change reaches a stage which affects the very character of the times there will always be some outstanding event, which conveniently enables us to fix historical dates. It seems to me that in the lengthening melancholy shadow of the dusk of the times the future historian will be able to fix the last A.F. of L. Convention as definitely marking the passing of a period in the history of organized labor: as represented by the A.F. of L.

Two Opposing Policies.

An editorial in the Weekly News of the A.F. of L. summarizes in “fifteen words” the “aggregate viewpoint” of the last Convention: “The workers must abandon old standards and ideals and must be awakened to changed conditions.” Now, what are these old standards and ideals which the last Convention definitely wishes labor to abandon? And what should take their place under the changed conditions; Says the report of the Executive Council:

“There are two opposing policies of making progress—one which makes force alone its agency for progress and the other endeavors through intelligent strategy to make progress without strife. The advocates of force believe that men’s decisions yield only to force and that labor must rely solely upon militant tactics. Those who believe that progress is made through increasingly better agreements and relations between employers and employes hold that problems must be settled by conference and discussion even after the fight is over, believe that it is therefore better to develop a strategy that will make the fight unnecessary and then concentrate on gathering facts and following policies that will enable the Union to sustain its proposals at the conference.”

So it is Intelligent Strategy as against Organized Strength. The adjectives of “alone” and “solely” are prefixed by the Executive Council upon the old standards of forceful, militant trade union struggle out of sheer generosity. There is not the slightest justification for these “alone” and “solely” in the history of trade unionism of “old standards and ideals.” The method of discussion and conference has never been neglected. The overemphasis is apparently meant not so much for the “old standards” as for the suggested new and opposing policy. Under this new policy all struggle based upon organized strength is to be abandoned for the gathering of facts to sustain the Union proposals at the conference table. Of late there were many danger signs indicating that the A.F. of L. was drifting into these shallow waters. The Mitten-Mahon agreement and the acclaim with which it was greeted was the most serious recent warning of the imminent peril. But what was a mere drifting tendency is now getting to be the official philosophy of the A.F. of L.

“For twenty years”—said Daniel J. Tobin, former treasurer of the A. F. of L., President of the Teamsters’ Union,—”I have been a faithful believer in the militant, forceful and aggressive policies of the American Federation of Labor. By this statement I do not wish to depreciate the importance of conciliation and arbitration. But as the labor movement prospered in the beginning through that spirit of self-sacrifice and determination which permeated the minds of the men who led in the great vanguard…it is my judgment, unless we continue to revive through some means or other, that spirit of individual interest; that determination to fight for what is right; use every argument and education which will compel our enemies and our government to recognize us as an important part of the life our nation; unless we do something along these lines, I am somewhat fearful of our continued success.”

Changed Conditions.

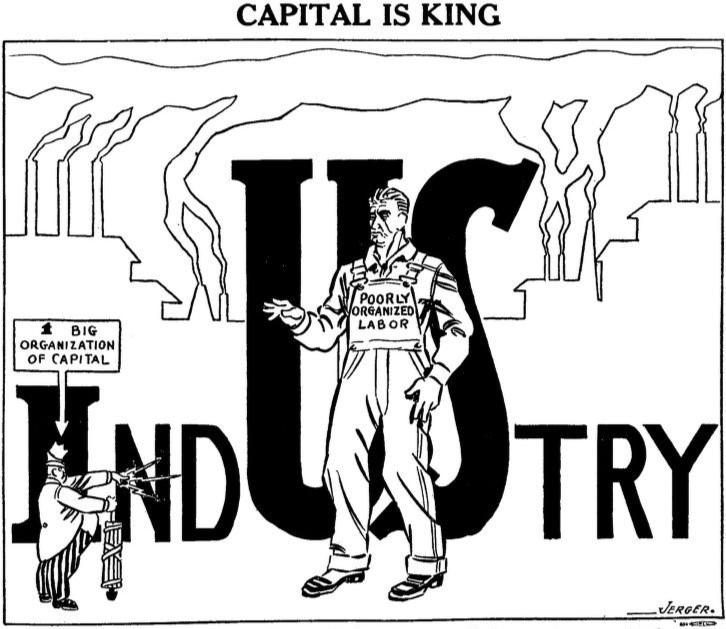

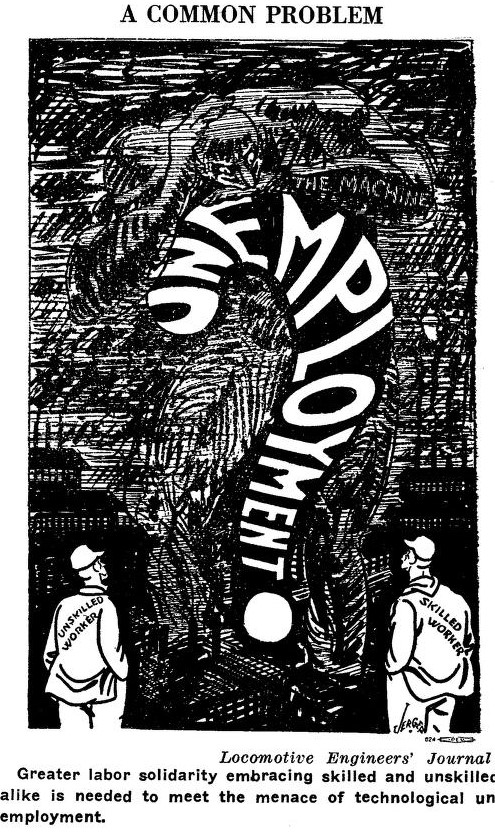

Changed conditions are advanced as the reason for abandoning the policy based on organized strength, in favor of strifeless “intelligent strategy”. Conditions have changed. Mass production and mechanization have reduced the bargaining power of the skilled craftsmen. Under the sweep of industrial centralization and mergers the trade unions have had all they could do to keep up their positions. The old standards and ideals have become inadequate. Trade and geographical divisions are a less and less controlling factors in the labor market. In an emergency any trade or industry may draw for its supply of help upon the entire labor market of the country. Job control within boundaries of a single trade has become less and less effective. The same holds good even to a greater extent with regard to wage control. The steam roller of mechanized industry has an irresistible tendency to level out wages in all trades and industries. In any case the low wage standard of the unskilled and unorganized have the effect of a dead ballast preventing the wages of even the best organized trades from rising anywhere near the level of the social wage standard of the A.F. of L. The productivity of labor has increased by leaps and bounds and has left the slow reduction of the hours of labor so much behind that we are confronted with the menace of a permanent reserve army of millions of unemployed, even during periods of so-called business prosperity. Trade unionism based on job and wage consciousness alone has proved to be a poor match to merger-capitalism of the giant-power age.

Under these changed conditions much greater organized strength is necessary if it is to be effective at all; much greater organized strength than could possibly be built upon that all too narrow foundation. Mass production calls for mass organization. Capitalist mergers cannot be met without labor consolidation, without the development of trade unionism into industrial unionism. Efforts towards job and wage control must be made coextensive with labor market of mechanized industry, demanding concerted action of organized labor as a whole. How can the subservient mentality of company unionism be defeated without the development among the workers of a deeper sense of human dignity, or without the development of that greater working class loyalty which alone makes for the realization that the good of the individual worker depends upon the progress of all the workers and that an injury to one worker is an injury to all the workers. The alignment of the courts and government on the side of the employers—of which the injunction is only the most undisguised expression—calls for an aggressive united labor struggle for political control.

Reaching the Employers.

In order to secure the indispensable increase in a much deeper and wider foundation is wanted, job and wage consciousness must be developed into class consciousness. But that means that organized labor must become frankly partisan. It is impossible for labor to stay divided against itself. However much some veteran labor fighters prefer it, labor cannot remain non-partisan in politics and retain unimpaired its militancy, forcefulness and self-sacrificing aggressiveness in the economic struggle. There is no alternative. Changed conditions permit of no such division of methods and policies. It is either organized strength throughout or lobbying throughout. To continue sailing under its own colors, labor must equip its own boat with the most modern powerful machinery, even if it has to be done amid stormy seas, unless it is prepared to lower its own colors and be taken in tow by the Mechanical Men of the Pirate Ship of Capitalism. In the latter case, all dependence upon organized strength must naturally be given up and recourse must be sought in the hope of reaching the captains ofthe pirate ship.

“Our purpose then” says the Executive Council “is exactly the same as that of all other intelligent progressive persons. We have sought to interpret the value and purposes of the functional services of trade unions so that both employers and employes might understand the value and the functions of trade unions.” So the purpose of the labor movement is the same as that of all other progressive and intelligent persons including employers. There is, then, really no good reason for a separate forceful and militant labor movement at all. For according to the Executive Council mere “intelligence assures a square deal to both groups (employers and employes) and abandons efforts on the part of one to profit by taking advantage of the other.”

How does it work out in practice?

The Metal Trades Department of the American Federation of Labor met at New Orleans a few days before the Convention of the A.F. of L., President James O’Connell reported that the Executive Council of the Department had a general discussion “on the question whether organized labor was making progress in the matter of contractual relations with employers; whether we were losing ground or making progress or holding our own with combinations of employers and Big Business.” The report does not say what conclusion the Executive Council arrived at. But as a result the “officers were finally advised to make an effort to get in touch with some leaders of Big Business,” with a view to securing better relations between “what is commonly called capital and labor.” In view of the declared sameness of purpose of intelligent progressive capitalists and laborers the Trades Department was rather doubtful whether there really is any such thing as what is commonly called capital and labor. But to proceed with the report: In compliance with these instructions the officers “have made a real effort” and “have succeeded in having two conferences with a few representative leaders in large business. These meetings for the time being are of a confidential nature and character and while we are not in a position to report any real progress plans are being worked out with a view of enlarging upon the start that has already been made, with the hope that some real results may be secured later on.” And here is another case, even more significant, taken from the same report.

The 1926 Convention of the A.F. of L. decided to inaugurate an extensive organizing campaign in the automobile industry.

“The officers of the A.F. of L. held several conferences with officers of various organizations recognized as having jurisdiction over workmen employed in the industry. A plan was worked out and an organizer of the A.F. of L. placed in charge of the work. He made an intensive survey of the industry but the difficulties encountered were so tremendous that the question of attempting to organize the employes was temporarily laid aside for the purpose of trying to reach the desired result through a different angle and direction.

“The President of the American Federation of Labor, after advising with the officers of our Department, and the officers of the Organizations interested, decided to reach the officials of some of the automobile manufacturing companies with a view of inducing them to enter into a conference with us for the purpose of trying to negotiate an understanding that might result in lessening the opposition of the officials of these companies to their employes being organized.”

This different direction, this method of reaching the lords of industry cannot be styled otherwise than lobbying. Having come face to face with changed general conditions demanding that the labor struggle be made co-extensive with the entire industrial scene and apparently shrinking from the tremendous difficulties involved, the A.F. of L. let itself drift into considering the labor struggle as unnecessary and objectionable, putting its entire reliance upon lobbying. But even lobbying depends for its effectiveness upon the ability to exert some pressure. The political lobbying of labor has been built upon the method of “rewarding friends and punishing enemies” among the candidates of the two capitalist parties—a type of pressure which is clearly inapplicable to economic lobbying.

The report of the Executive Council would indicate that two methods are to be depended upon for reaching the employer. These methods are, first, to prove that “the Union is an agency which the employers may turn to for cooperation for mutual benefit.” Secondly, that “in times of crises industrial leaders are quick to realize that the constructive ideals of labor are a tremendous asset,” and it is merely necessary to convince them that these constructive ideals “are an equal industrial asset” even “when conditions are normal.” “We”, says the report of the Executive Council” have no revolutionary purpose to overthrow the present social system.” But “wherever there is discontent among the workers arising from unsatisfactory conditions of employment, lower wages, long hours of work, unemployment, that is the point where the Communists concentrate their work.”

So the labor lobbyist is to have two major arguments. The employer must recognize the regular trade unions because they are constructive and good, because they are “studying problems of cooperation and increasing union services”, because they actually can do for the employer as much as any company union and more. Then, again, the employer must recognize the regular trade union because otherwise the Bolsheviks will get him.

We agree with Daniel J. Tobin that this is a time to be open, plain, fearless and above board. Trade unionism by lobbying spells disintegration. It spells the loss of interest on the part of the membership resulting in a great falling off of members in international unions. Neither can it accomplish any results in reaching the employers. As President O’Connell reports “correspondence has taken place and attempts have been made to secure appointments for conferences but without any effective results…While they have not given up hope that sooner or later we may be able to reach some of those employers, who would be willing to sit down and confer with us, up to the present we are not in a position to even report progress.” Spiritually trade unionism by lobbying spells starvation, starvation unto very death: It explains why one of the oldest delegates known for his loyalty to the A.F. of L., advised a friend to “pay a visit for a day to any cemetery and you will find more life and interest there than at the New Orleans A.F. of L. Convention Cemetery.” It explains the mechanical ready unanimity on all questions, because it is impossible to get really excited or enter into heated discussion of the methods of lobbying, whether it be intelligent strategy or otherwise.

To Overcome Disintegrating Processes.

Trade unionism by lobbying finally explains the excessive zeal of the Convention to disassociate itself from anything that might look to new social order theories, however distantly related. Brookwood must be ostracized without as much as a hearing because it does not believe that capitalism is an efficient, just or humane system and wants it replaced by cooperative commonwealth under the control of producers. All reference to that eminent educator, Prof. John Dewey, must be eliminated from the records because he had the temerity to visit Soviet Russia and to find merit in the new social system established there. For the same reason the suggestion of Fraternal Delegate Marchbank of the British Trades Union Congress to the effect that all wars are capitalist wars must be rebuked with asperity by a 100 per cent patriotic declaration that “while anxious for the development of peace”…the working men of America stand ready at all times to “rally to the support of our institutions and of our government.’ How else can trade unionism by lobbying show itself to be an industrial asset to the employers in normal times as well as in times of crises?

As far as the A. F. of L. is concerned the last Convention marks the passing of trade unionism by organized strength and the substitution of trade unionism by lobbying. We have, however, unbounded faith in the invincible inherent power of organized labor. We doubt not that the labor movement will overcome these processes of disintegration and will find a way to check the dangerous drifting or to hew out a different channel for its creative functions. The dusk of yesterday may throw its shadow upon the early dawn of the morrow, but it merely foreshadows the advancing day of the labor movement, triumphant in its class conscious militancy, unity and solidarity. In spite of its own passing weaknesses, Labor omnia vincit.

Labor Age was a left-labor monthly magazine with origins in Socialist Review, journal of the Intercollegiate Socialist Society. Published by the Labor Publication Society from 1921-1933 aligned with the League for Industrial Democracy of left-wing trade unionists across industries. During 1929-33 the magazine was affiliated with the Conference for Progressive Labor Action (CPLA) led by A. J. Muste. James Maurer, Harry W. Laidler, and Louis Budenz were also writers. The orientation of the magazine was industrial unionism, planning, nationalization, and was illustrated with photos and cartoons. With its stress on worker education, social unionism and rank and file activism, it is one of the essential journals of the radical US labor socialist movement of its time.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/laborage/v28n01-Jan-1929-Labor%20Age.pdf