A native of the Aran Isles, Daily Worker columnist Tomás Ó Flaithearta returns to Ireland after an absence of 14 eventful years to survey the state of the workers’ movement a decade after the 1916 Rising.

‘Life and Struggles in Ireland’ by T.J. O’Flaherty from the Daily Worker Saturday Supplement. Vol. 3 Nos. 170 & 182. July 31 & August 14, 1926.

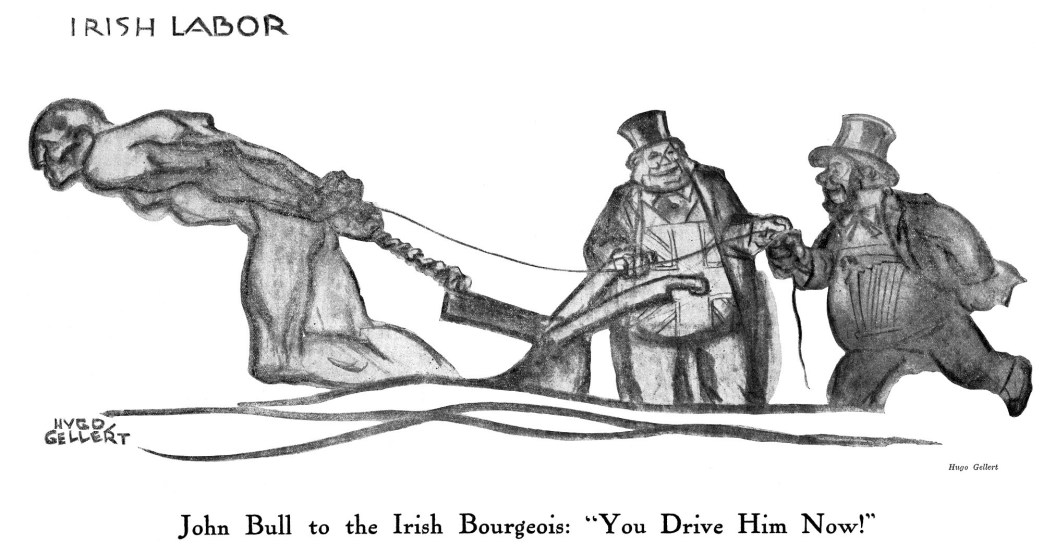

HOW NOW stands the Irish labor movement? What has become of that militant spirit that challenged the admiration of the workers of the world during the great lockout in Dublin in 1913, and again 1916, when James Connolly, the social revolutionist at the head of his citizen army, in alliance with the nationalistic Irish Republican Brotherhood, threw a monkey wrench into the war machinery of the British war cabinet, or later on during the years of war and terror that followed, stood for and fought for the rights of labor against the armed forces of the British crown and against the Irish employers who cared not what government helped them wrest more profits from their wage slaves.

Having followed the progress of the Irish labor movement from a distance for the past fourteen years, I was deeply interested in getting first-hand information of the present situation and also the story of the most stirring and eventful years in Irish history from the lips of those who have been at the helm of the movement since the guns of a British firing squad wrote finis to the career of James Connolly, the outstanding revolutionary thinker that the Irish labor movement produced.

The Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union is the backbone and very much flesh and blood of the Irish labor movement. Much of what I learned about it was known to me already, but it can bear repetition,

There was general agreement that apathy and indifference existed at present in the trade union movement, that considerable dissension was prevalent in the ranks, that the split in the transport union weakened that organization and that the establishment of the Free State government with Irish instead of English agents of capitalism did not mend matters for the Irish proletariat.

Ireland, including the counties under both north and south governments, has a population of a little over 4,000,000 inhabitants. The north is the most highly industrialized section. Yet the northern workers are poorly organized, while the southern countries are covered with a network of trade union locals, which wield considerable influence, even tho many of them have been weakened as a result of the desperate struggle of the last two years. The story of the transport union is interesting. It was organized under the leadership of Jim Larkin and figured in many spectacular labor struggles, culminating in the great Dublin lockout of 1913, when the Dublin employers decided to crush the union by refusing employment to any worker who did not tear up his card in the I.T. and G.W.U. The answer of the workers to this impudent demand was defiance.

The strike was not successful or, rather, the lockout was. The men went back under whatever conditions they could secure. The employers were jubilant. Jim Larkin went to the United States on a speaking tour and was not able to return for eight and a half years, very eventful years.

In the meantime the Irish rebellion had taken place, and James Connolly, secretary of the Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union, as well as the leading exponent of Marxism in Ireland, if not in Great Britain, fell before a British firing squad during the regime of the liberal Asquith, whose cabinet included Mr. Arthur Henderson, socialist. Henderson did not move a finger to save a man whom he once called his comrade in the international army of labor.

William O’Brien, co-worker with Connolly in the socialist movement in Ireland in its infancy, told me the story of the union’s struggles. after the defeat of the Easter week rebellion. He told me of Connolly’s last farewell as he set out to challenge the power of the British empire with arms.

“We are going out to get slaughtered,” he said to O’Brien on the morning of the rising. He knew there was no chance for success. But retreat was impossible. The welfare of the union was foremost in his mind. “The union will need your services,” he said to O’Brien as he bid him goodbye.

O’Brien is general secretary of the Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union and the dominant personality in the official trade union movement.

He spoke frankly about the strength of the union. Instead of a membership of 100,000 or more who were on the rolls a few years ago, the number is now down to 50,000. O’Brien insisted that only dues paying members are considered in this reckoning.

After the defeat inflicted on the Dublin workers in 1913 and until after Connolly’s execution in 1916 the transport union was weak numerically. It hardly existed outside of Dublin. Connolly tried to set it on its feet and systematize its functioning. It is very doubtful if it had more than 5,000 members in all Ireland when the rising took place.

After the Easter week revolt a decided change took place. The workers who were hitherto hostile to the union, largely owing to the poisonous propaganda put out by the capitalists, thru their allies, the press and the pulpit, joined the organization on the crest of a wave of national emotionalism. And from then until the treaty was signed the transport union was the backbone of the national struggle against the British government, tho after Collins and Griffith signed the treaty in London Eamonn De Valera, now leader of that wing of the Irish republican movement which is willing to participate in the Free State parliament under certain conditions, entered into a compact with the pro-treaty forces, which was in effect a political pact to divide the constituencies between them. Both called on the Irish Labor Party not to contest the elections on the plea that no class interests should be stressed when the Irish nation as a whole needed unity. The Irish Labor Party declined this counsel and elected 17 out of the 18 candidates put forward.

During the struggle with the British government during the world war and afterwards the Irish labor movement co-operated with the Sinn Fein organization. In fact, the union members gave their first allegiance to the nationalist organization. The general strike against conscription as well as the refusal of the unions to transport soldiers or ammunition during the Black and Tan period could not be successfully carried out by the union unaided.

While the war was on and for some years afterwards the Irish workers were able to secure substantial wage increases thru the union. This was a strong incentive to join. But when depression set in the fair-weather members refused to pay dues. The union was not getting them anything, they claimed.

Another weakening influence was the conflict between Free Staters and republicans inside the ranks. The official position of the union was that the republican faction cared as little for the interests of the workers as did the Free Staters. This was unquestionably true as far as the leadership was concerned, tho it might be argued that a labor movement following in the footsteps of James Connolly would consider it its duty to assume the leadership in the struggle for the emancipation of Ireland from British rule as well as the industrial freedom of the working class.

The leaders of the Sinn Fein had little sympathy with the proletarian movement. At the annual convention of the transport union held while the Russian famine was at its height a resolution was passed that the union, in cooperation with the farmers, send a shipload of food to the Russian workers and peasants as a gesture of friendship from the Irish people. The transport leaders believed they could not successfully carry out this plan without the support of the Sinn Fein movement. A committee interviewed De Valera and Arthur Griffith and asked their assistance. De Valera was opposed, tho Griffith favored the proposition. But De Valera’s position carried. The republican politicians were willing to use the labor movement to stop Black and Tan bullets, but were not willing to give reciprocal aid.

At present the republican movement is split into two factions, one led by Eamonn De Valera, the other under the leadership of Mary MacSwiney and Rev. Michael O’Flanagan, a catholic priest who does not work at the profession.

De Valera has come around to the point of being willing to enter parliament provided he is not obliged to take the oath of allegiance to the king of England. The Irish labor movement and Communists in Ireland and elsewhere held from the beginning, particularly since the Free Staters won in the civil war, that the anti-imperialist elements should participate in the Free State parliament for agitational purposes. De Valera now finds his following slipping away from him. Hence the new departure.

The MacSwiney faction is against participating in the parliament under any condition. They make a moral issue out of it and feel that their republican virtue would be sullied by entering the Dail. Tho republican sentiment is very strong in Ireland, so strong, indeed, that nobody who does not claim to be a republican at heart could get elected in any southern constituency, outside of a few university seats. The masses are disgusted with the Gilbert and Sullivan antics of the republican factions and growing more bitter against the anti-social program of the Free State government. Another article on Ireland will appear in next issue.

II.

THE Irish Trade Union Congress is the supreme organ of the Irish trade union movement. The great majority of the organized workers are affiliated with the congress. The dominating factor in this body is the Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union.

Hitherto the executive committee of the congress functioned as the executive of the Irish Labor Party. There was no political organization until recently, when it was decided to reorganize the labor party on the basis of individual membership, with a program that makes appeal to small farmers, small business men and the city and agricultural proletariat and intellectuals.

Active work is now in progress for the organization of the labor party under the direction of Archie Heron, financial secretary of the Transport Union, who was “loaned” to the labor party by his union for the work. While an invitation is extended to the left wing elements–I presume the Communists are meant–it is a rather left-handed invitation, as the admonition goes with it that proper political decorum will be insisted on, and undoubtedly the court of etiquette will be controlled by those who seem to think that Communists can only be good when dead or else afflicted with mental and physical paralysis.

The new development in political organization of the working class is a great step forward, even tho it will inevitably be under the conservative influence of Thomas Johnston and his followers for some time to come. It is the first time in Irish history that steps have been taken to organize a mass political party representing the interests of the workers and peasants.

What about the status of the various groupings, political and industrial, in the Irish labor movement?

First comes the Transport Union, with 50,000. members and a weekly publication, the Voice of Labor. The union has a reputation for militancy and still retains that reputation. Its official organ sometimes is more like a mouthpiece for the labor party than for the union. It lacks a consistent policy, but is decidedly to the left, that is, comparatively. Compared to the official organs of American trade unions, it is revolutionary. It is more advanced than Advance, organ of the American Amalgamated Clothing Workers, and much less cynical. The Transport Union officials, regardless of their deviations, have spurned the idea of allowing the union to dabble in business. They favor co-operative effort, but they have not yet, at least, descended to the level of excusing business ventures with the argument that this is the way to put the capitalists out of business, as some labor bankers and labor coal operators have done.

The voice of Labor is friendly to Soviet Russia and hints that it favors the organization of a unified trade union international with the inclusion of the Russian trade unions. The union is affiliated with the International Transport Workers’ Federation, but the Irish Trade Union Congress is neither affiliated with reformist Amsterdam nor with the revolutionary Red International of Labor Unions. At the Derry congress of the I.T.U.C. held last year a motion was made, I believe by Archie Heron, that the congress should affiliate with Amsterdam in order to be in a position to assist the British trade unions in their efforts to bring about a meeting between the two internationals with a view towards unity.

Others took the position, O’Brien among them, that it was by no means impossible that a break between Amsterdam and the British unions would take place, the latter possibly withdrawing from the I.F. of T.U. As the Irish trade unions never had any international affiliations, not even with the British, as has been erroneously assumed, it would require an educational campaign to convince the Irish workers they should affiliate, and in the event of a rupture between the left wing elements already affiliated with Amsterdam, resulting in a withdrawal, the Irish unions could not stay and they could not withdraw without another propaganda campaign for withdrawal. Therefore the best policy was to express approval of the movement for international unity and await developments. This position carried. I found the officials of the Transport Union deeply interested in the work of the Anglo-Russian committee and sympathetic with its aims.

There are several sections of British unions in Ireland that are not under the control of the Irish Trade Union Congress. In fact, the congress, even tho it is clothed with more power, in emergency situations, than the A.F. of L., is nevertheless very much like the “rope of sand” that Samuel Gompers compared the federation to at the Montreal convention.

Is there a left and right wing in the Transport Union?

Undoubtedly there are left and right tendencies, as in all organizations, but the left has not yet assumed organized form. William O’Brien, general secretary, gave me one explanation why such was the case.

He attributed this phenomenon to the rebellion, the Black and Tan terror, and the civil war between republicans and free staters that followed. The members of the union, or many of them, participated in all those actions. O’Brien was arrested and imprisoned after the rebellion, with practically all members of the executive. With bombs “bursting in air” burnings, executions taking place daily and nightly, there was little time to devote to inner union politics. The big job was one of defense against the external foe.

WITH the final military defeat of the republicans, the union members naturally began to look for something else to fight about. It looked as if a left wing was in the process of formation. Several active members of the union were in the Communist Party. In fact William O’Brien and Cathal O’Shannon were originally members of the Communist Party, as they were members of the Irish socialist party, which James Connolly organized. Cathal O’Shannon is editor of the Voice of Labor.

No sooner was the civil war over than another obstacle to the development of a left wing appeared. This was a bitter factional fight which ended in the organization of the Workers’ Union of Ireland. That war is still on, without any indication of a truce, armistice or peace. The most progressive of the transport union members who were not affiliated with the virus of dual unionism stayed with the parent organization and raised the slogan of unity. As the secessionists laid claims to the mantle of radicalism, many of the healthy but unseasoned progressive split with the I.T.G.W.U. The result has been almost disastrous for the trade union movement as a whole and a deterrent to the development of a left wing.

Nevertheless, my opinion is that the Transport Union is the center of gravity of the Irish labor movement, and that from within its ranks will be developed the leadership that will play the big and leading part in the class struggle in Ireland in the future.

The Workers’ Union of Ireland does not exist outside of the city of Dublin to any considerable extent. How many members it has on its rolls appears to be a mystery. In many respects it reminds me of the O.B.U., that was organized by Ben Legere in Lawrence, Massachusetts. Ben was a resourceful fellow and while he remained in Lawrence he was usually able to stage a demonstration of some kind. Incidentally, he was an actor by profession. Ben’s members did not have to bother much about paying dues. Their moral support and ideological kinship was sufficient. But when Ben left Lawrence the O.B.U. disappeared.

The Workers’ Union of Ireland expects its members to pay dues, but the executive relies more on a rather flourishing coal business than on dues payments for revenue. It must be admitted that Jim Larkin is a very resourceful leader. Indeed, it is very doubtful if anybody else could have thought of the devices he brought into play to defeat his enemies.

The coal dockers were on strike. Most of them, I believe, were on the rolls of the Workers’ Union. Scotch coal companies had a practical monopoly on the Dublin market. Larkin conceived an idea and then took action. He organized a coal company, made a contract with a British company to supply him with black diamonds and now the union is doing a flourishing business with the Scotch sucking their thumbs.

Of course everything is not easy sailing. There is sometimes trouble about cash and quarrels with committees over this thing and that thing, and there is also a feeling that business and unionism do not go hand in hand.

The Workers’ Union of Ireland has no publication. Its organ, the Irish Worker, went out of business over a year ago.

The membership is probably in the vicinity of one thousand, tho this cannot be officially learned, as no figures have been made public.

There are two central bodies in Dublin, the Workers’ Council and the Dublin Trade Council. The former is dominated by the Transport Union and was organized in the early days of the Russian revolution. The latter has not a large affiliation and is dominated by P.T. Daly, formerly an ally of Larkin, but now a member of the executive committee of the Workers’ Party of Ireland, the only organization in Ireland of a Communist character.

The Workers’ Party of Ireland.

SINCE the Communist Party of Ireland was liquidated in 1923 there has been no organization there that systematically issued Communist propaganda. The members of the dissolved party maintained themselves as a unit in a Connolly educational society. Under the guidance of Robert Stewart, now acting secretary of the Communist Party of Great Britain, plans were made to launch a Workers’ Party in May, 1925. The program and platform was published and the prospects were bright, when, to the dismay of the organizers, a few days before the scheduled date of the conference that was to launch the party, a statement appeared in the public press to the effect that the Workers’ Union of Ireland would have nothing to do with it. The project was then indefinitely postponed.

This year, however, a Workers’ Party was organized, in which neither the Transport Union nor the Workers’ Union are officially represented. The active leaders of the new party are former members of the Communist Party of Ireland. The infant party has not much prospect of immediate success, as the objective conditions are not at all favorable to the rapid growth of a Communist Party. Nevertheless, those comrades seem to be tackling a difficult job with courage and enthusiasm. Having no funds to publish a printed sheet, they are issuing a mimeographed bulletin called “The Irish Hammer and Plough” from 47 Parnell Square, Dublin. Tho not an affiliated section of the Communist International, the party follows the political and industrial line of the Comintern and urges a united front of the warring trade union factions against the employers.

Evidently the comrades have learned a good deal from their past mistakes and have discarded the leftism with which the late Communist Party was afflicted.

The rebel spirit which the British failed to quench is not dead in Ireland. But it is taking a nap. Peadar O’Donnel, militant republican leader, and one of the few in that movement who has a social program for the workers, attributes the present apathy to the strain of the long-drawn-out struggle that lasted eight years without intermission. The general opinion is that this condition will soon pass away and that a more militant spirit will soon manifest itself among the Irish workers and the republican nationalists.

Communist propaganda is sorely needed in Ireland and the attempt of the Workers’ Party of Ireland to supply this want deserves every possible encouragement.

The Saturday Supplement, later changed to a Sunday Supplement, of the Daily Worker was a place for longer articles with debate, international focus, literature, and documents presented. The Daily Worker began in 1924 and was published in New York City by the Communist Party US and its predecessor organizations. Among the most long-lasting and important left publications in US history, it had a circulation of 35,000 at its peak. The Daily Worker came from The Ohio Socialist, published by the Left Wing-dominated Socialist Party of Ohio in Cleveland from 1917 to November 1919, when it became became The Toiler, paper of the Communist Labor Party. In December 1921 the above-ground Workers Party of America merged the Toiler with the paper Workers Council to found The Worker, which became The Daily Worker beginning January 13, 1924.

PDF of issue 1: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/dailyworker/1926/1926-ny/v03-n170-supplement-jul-31-1926-DW-LOC.pdf

PDF of issue 2: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/dailyworker/1926/1926-ny/v03-n182-supplement-aug-14-1926-DW-LOC.pdf

In the 1926-27 period Tom O’Flaherty was one of Jim Larkin’s fiercest critics, leading Larkin to complain bitterly to the Comintern about O’Flaherty’s attacks in the Daily Worker. The Comintern ordered O’Flaherty to desist, but he carried on. It would be interesting to see O’Flaherty’s anti-Larkin articles. The criticisms in the two pieces featured here are tame compared to some of the things O’Flaherty had to say.

LikeLike