A rare article from your host, however the plan is to do more such brief summaries from which to link posts in the archive to. For the U.S. Left, 1919 was a turning point; both a culmination of past battles and a new departure for future ones. Below is a synopsis of those events. The Socialist Party, with its tens of thousands of members and numerous resources, would implode under the pressure of an insurgent, but divided Left Wing inspired by the European revolutions. By the end of the year a number of new parties, including three Communist, would form. Below is a look at how that process unfolded and its consequences. In the next addition we will look at the political biographies of the leading figures of both the new Communist and Communist Labor Parties.

‘1919: War in The Socialist Party, Birth of The Communist Movement’ by Matt Siegfried (Revolution’s Newsstand).

Class Struggle in the Socialist Party

The Socialist Party had a background of long-standing deep divisions, particularly over union and electoral policy. Both played the leading role in the Party’s large left-right struggle, in 1911-13, around industrial vs. craft unionism, parliamentary political action vs. mass political action. Those divisions remained and found new forms as in 1914 World War One began.

Though not yet with direct U.S. participation, the Socialist Party confronted new issues, leading to a profound crisis that raged from 1916-1919 and would lead to its implosion. Emerging issues, finding echoes in the old, included a new International, anti-war policy and its implementation, the role of Language Federations, race and immigration, state repression and legal recourse, the woeful tenure of Meyer London in Congress and other elected officials, and the increasingly bureaucratic rule of the right-wing leadership over the left-wing rank-and-file.

Gathering in emergency conference as the U.S, formally entered the war in the 1917, the Party agreed to a rhetorically strong anti-war, internationalist resolution–which saw a welcome bolt from the Party by the pro-war right. However, massive differences remained over how to oppose the war and relate to a world entering a revolutionary upsurge. The far left echoed the revolutionary cry from Europe of turning the imperialist war into a civil war, while the center-right focused on the Sisyphean task of lobbying Washington war-mongers to protect civil rights.

In 1919, not counting the Language Federation with their tens of thousands members, the Socialist Party numbered around 80,000 with dozens of paid staff, elected officials, club houses, and allied newspapers—in over a dozen languages. The party had reversed its decline in the previous few years, spurred by mass anti-war sentiment, union struggles, and an emerging vocal, Marxist left exemplified by the Socialist Propaganda League of America. But most importantly–the beginning of Europe’s unprecedented revolutionary wave.

Likely constituting most Party activists, and certainly its most active cadre, left wing locals, cities, states, and circles widely existed. Though no formal organization or political cohesion existed. Growing calls to consolidate and clarify a formal Left Wing grew wider and louder by early 1919.

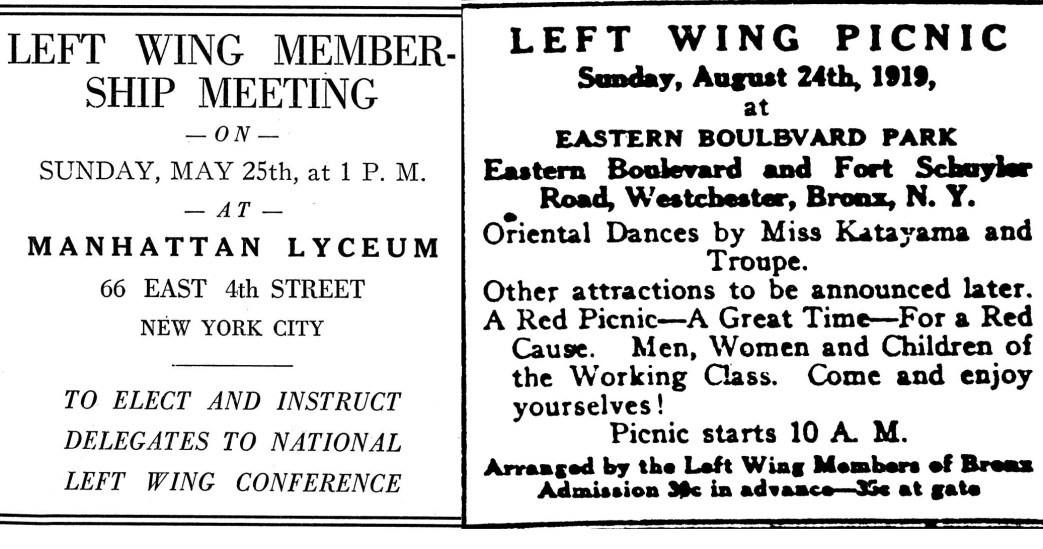

In a blatant attempt to stem the tide, the S.P.’s 15-person lame-duck National Executive Committee met on May 24-25, before the new leadership elections scheduled for June. The N.E.C. consisted of National Executive Secretary Adolph Germer, International Secretary Morris Hillquit, Victor L. Berger, Stanley J. Clark*, George H. Goebel, Emil Herman*, Dan Hogan, Fred Holt, Ludwig E. Katterfeld*, Frederick Krafft, Walter Thomas Mills, James Oneal, Abraham Shiplacoff, Seymour Stedman, Alfred Wagenknecht*, and John M. Work. (*occasionally, or always left). The meeting, just reaching quorum, voted 7-3 to expel the whole of Michigan’s Socialist Party for a clause dismissing a parliamentary strategy. In addition, for public support of the newly released Left-Wing Manifesto, seven language federations, with over 30,000 members were expelled. Seven people, half lawyers, expelled thousands of Hungarian, Latvian, Lithuanian, Polish, Russian, South Slavic, and Ukrainian proletarians. To add insult, the Translator-Secretaries were thrown out of the headquarters.

While the Left Wing and the Party’s foreign-born members certainly overlapped in many places, they were not the same. Part of the impulse of the right-wing’s action was surely a sop to jingoism and the long desire by some in the right to fully ‘Americanize’ the party.

The Left Wing

In early June, regular elections were held for the Socialist Party’s 15-person N.E.C., National and International Secretaries. The vote saw a crushing Left Wing victory across the board. Winning both leading positions and eleven of the fifteen N.E.C. seats, elected were National Executive Secretary, pro-tem Alfred Wagenknecht*; International Secretary, Kate Richards O’Hare*; for National Executive Committee: Dennis E. Batt*, Dan Hogan, Louis C. Fraina*, Kate Sadler Greenhalgh*, Fred Harwood, Nicholas Hourwich*, Ludwig E. Katterfeld*, John Keracher*, Edward Lindgren*, William Bross Lloyd*, Mary Raoul Millis, Patrick Nagel, Marguerite Prevey*, C.E. Ruthenberg*, and Harry M. Wicks*. (*left or lefty).

To give a sense of scale of the victory; for International Delegate, the incumbent and Party grandee Morris Hillquit received 5629 votes, his left challenger Kate Richards O’Hare, 12,346. Votes for the N.E.C.: former National Secretary Adolph Germer who served from 1913-1916 received 3,843 votes and pioneering Communist Louis C. Fraina received 13,447. Former Congressperson Victor Berger, after Debs the Party’s most recognizable figure won 4,465; New party member recently returned from Russia John Reed took 16,074 votes; N.Y.C. Council Member the lawyer and Party veteran Algernon Lee took 1,616, and while future Secretary of the Communist Party C.E. Ruthenberg won 10,067; James Oneal, who had been on Party leadership since 1901, took 1,726 votes, while left-wing anti-war prisoner Alfred Wageknecht won 10,358.

In response to their total defeat, the out-going N.E.C simply ignored the results, claiming the authority of the coming September, 1919 Chicago Emergency Conference to decide on a new leadership. For good measure, they also expelled the Massachusetts State Party which had just voted for the Left Wing.

The duly elected majority Left Wing leadership met on their own authority, sending defeated National Secretary, who refused to concede, this terse notice:

“July 29, 1919.

“Dear Comrade:

“At the meeting of the new National Executive Committee, held in Chicago on July 26 and 27, the following motion passed:

“That the office of the National Executive Secretary be declared vacant inasmuch as the present incumbent refuses to perform his duties as National Secretary by refusing to tabulate the vote in referendums expressing the will of the membership and further refuses to recognize the regularly elected National Executive Committee.”

“Yours in Comradeship, A. Wagenknecht, Executive Secretary, Pro Tem.”

While the new leadership may have won the election, the recalcitrant Right retained all the Party’s resources, books, and authority. The situation was untenable. On June 4, 1919 the left-wing ‘Ohio Socialist’ issued a call signed by Local Boston, (Louis C. Fraina, secretary); Local Cleveland, (C.E. Ruthenberg, secretary); and the Left Wing Section of the Socialist Party of New York City (Maximilian Cohen, secretary) to formalize the Left Wing in New York City on June 21-24 and collectively decide the next steps. Meanwhile, the Michigan group, the earliest to proclaim for a Communist Party, had already issued and invited comrades to join them during the Socialist Party’s Emergency Conference on September 1, 1919 to establish the new Party.

Though the Conference was able to issue a manifesto, it was clear that the many differences over tactics and orientation were insurmountable. Fights at the conference began over whether language federations would have their own delegates in addition to those already elected. This complicated the main contention, a splitting one, in the Left Wing. Many of the Federationists favored an immediately split with the Socialist Party, endorsing the September 1st call, while the majority argued for bringing the fight to the Emergency Convention to enforce the left’s legitimate leadership over the right. That position would win. But it would not be accepted by those who disagreed.

A “National Council of the Left Wing” was elected, John Ballam, Maxmilian Cohen, I.E. Ferguson, Louis C. Fraina, Benjamin Gitlow, James Larkin, Eadmonn MacAlpine, C.E. Ruthenberg, and Bertram Wolfe; none of the elected from the Federations. Other issues, some overlapping with the former divisions, included differing orientations to the A.F.L. and I.W.W., parliamentarism, question of above vs. belowground work, and the role of the press.

The first Left Wing Conference ended in disunion, with the two main sides committed to carrying out their own perspectives. An auger of the future. The disunity among the Left Wing made it impossible, along with the undemocratic and arbitrary S.P. leadership, to capture the Party for what was the majority left-wing of its members. There were also hundreds of the most influential and experienced revolutionary leaders in prison at the time, unable to participate in the debates and provided their valued counsel. Comrades like Debs, Larkin, and Haywood to name only a few.

The Chicago Conventions

The long-awaited S.P. Emergency Convention was held August 30 to September 5, 1919. Given the mass and individual expulsions the previous months, as well as many denied credentials, the Convention was overrepresented by a compact right wing while a divided Left Wing was under-represented. Those who chose to fight in the S.P. were quickly routed by every bureaucratic maneuver and withdrew nearby to constitute themselves as the Communist Labor Party on August 31, 1919 with headquarters to be in Cleveland, Ohio.

Elected to C.L.P. Leadership were National Executive Secretary: Alfred Wagenknecht; National Executive Committee: Max Bedacht, Jack Carney, L.E. Katterfeld, and Edward Lindgren, Editorial Board: Edward Lindgren, Ludwig Lore, and A. Raphailoff, Organization Director: L.E. Katterfeld, Labor Committee: Charles Baker, L.K. England, Benjamin Gitlow, R.E. Richardson, Arne Swabeck, International Delegates: John Reed and Alfred Wagenknecht. The C.L.P. immediately applied for membership of the Third International.

Happening in Chicago concurrently, the Left Wing who had endorsed the September 1st call to form a new Communist Party met with 137 delegates. Roughly divided into three tendencies; the majority around the Russian Federation which might now be classified as ultra-left, the Left-Wing Council group around Ruthenberg, Lovestone and Fraina, and the Michigan comrades around Dennis Batt and John Keracher. That last group would leave the conference, constituting the very first Communist Party split, at the very first conference, soon to form the Proletarian Party of America.

To be headquartered in Chicago, the newly elected leadership of the (old) Communist Party of America included:

National Secretary: C.E. Ruthenberg, Editor of Party Publications: Louis Fraina. International Secretary: Louis Fraina.

International Delegates: C.E. Ruthenberg–Nicholas Hourwich–Russian Federation, Alexander Stoklitsky–Russian Federation, I.E. Ferguson.

Executive Council: C.E. Ruthenberg–Louis Fraina–Charles Dirba–I.E. Ferguson–K.B. Karosas–Lithuanian Federation, John Schwartz–Latvian Federation, Harry Wicks. Additional Central Executive Committee Members: John J. Ballam, Alexander Bittelman–Jewish Federation, Maximilian Cohen, Daniel Elbaum–Polish Federation, Nicholas Hourwich–Russian Federation, Jay Lovestone, Oscar Tyverovsky–Russian Federation, Paul Petras–Hungarian Federation. The Party also immediately applied for membership of the Third International.

The week of the Socialist Party Emergency Conference saw no less than five organizations stumble away from the proceedings: the rump Socialist Party, the Committee for the Third International (inside the S.P.), the Michigan-based Proletarian Party, the (old) Communist Party of America, and the Communist Labor Party. In addition many thousands of revolutionaries, particularly in the I.W.W. and those unaffiliated were also participants in the various left reconstitutions that the Russian Revolution opened up.

All of these organizations would see further splits and fusions, and it would take until the formation of the Workers Party in late-1921 until a large majority of Third Internationalist were in a common organization. Years which would see the revolutionary wave that inspired these new departures recede in much repression and demoralization as hopes for a quick move to the New Day faded in disappointment. But they did not defeat the left.

Next, we will look at the biographies of the leading figures, founders of the emerging Communist movement.

Excellent post and history lesson chuq

LikeLike

Thanks so much!

LikeLiked by 1 person

A valuable source and you are very welcome chuq

LikeLike