The second half of Kantorovitch’s defense of Marxism’s dialectical materialism relates how Marx and Engels challenged Hegel’s idealism and all metaphysical conceptions.

‘The Social Philosophy of Marxism, Part Two’ by Haim Kantorovitch from American Socialist Quarterly. Vol. 1 No. 3. May, 1932.

III. SYSTEM AND METHOD

THE revolutionary potentialities of the Hegelian dialectic method lay dormant within the narrow walls of his idealistic system. Did Hegel himself realize what revolutionary possibilities lay hidden in his method? Some are inclined to think that he did, but did not care to make full use of them. Was not Hegel a radical and libertarian in his youth? Did he not, together with Schelling, plant a liberty tree, when both were young? Did he not fill his album with such exclamations as “Vive la Liberte!” “Vive Jean Jacques!” etc.

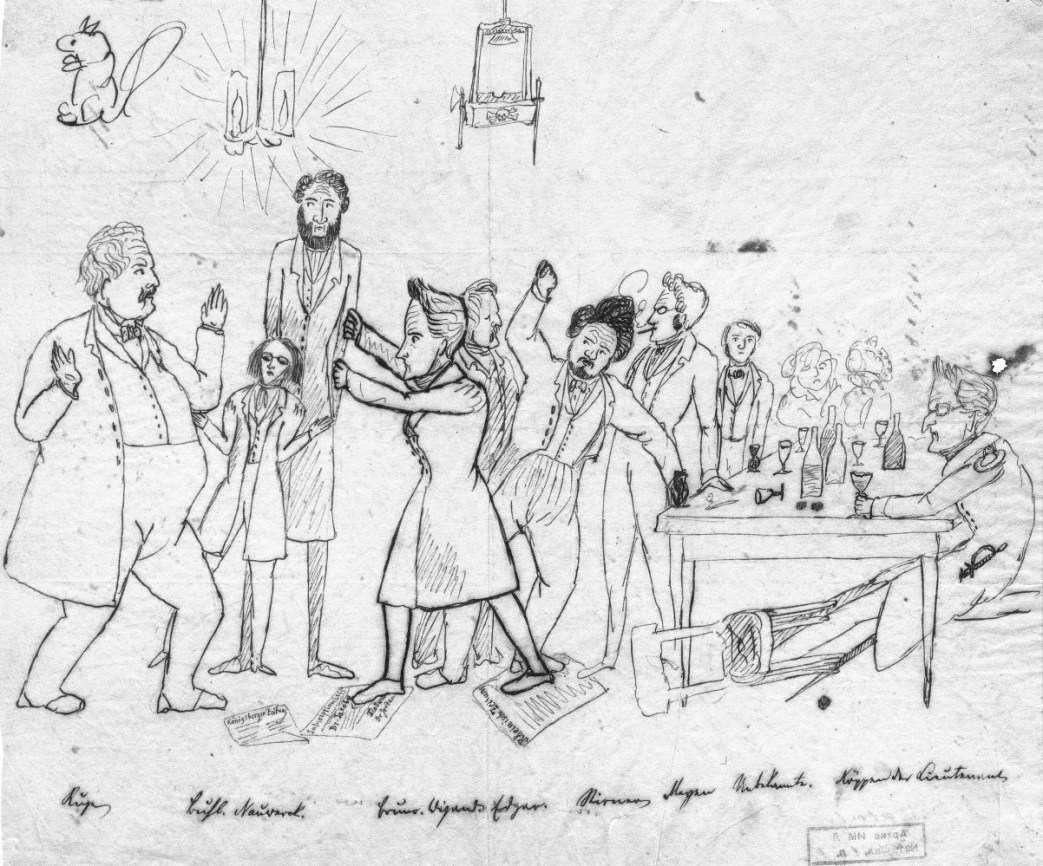

Heinrich Heine has indeed accused him of “intellectual cowardice”. “Once when I seemed puzzled by the words, ‘Everything that exists is reasonable,’” Heine relates, “he gave a strange laugh and remarked: ‘But this also means that everything that is reasonable ought to exist’. Then he became restless, and uneasily looked around. Seeing that no one, except Heinrich Beer, heard him, he felt relieved.”1 It does not matter whether what Heine relates is truth or fiction. It shows what people like Heine thought about Hegel. Whether Hegel himself did or did not realize the full revolutionary import of his method, he certainly did not use it to its utmost. It is true that it often helped him to gain a much broader, deeper and truer insight into the world, especially into human history. In his historical studies, he was from time to time able to forget his idealism, and look at one or another historical incident from a realistic, dialectical point of view. Realism coupled with dialectics could produce great results. But these were only the exceptional “happy moments”. In these exceptional moments he did attain brilliant results; often he thus really gained a glance behind the scenes of history, and dimly perceived the real forces shaping human destiny. Thus, he was able, for instance, to see the history of philosophy, not as the “story” of unsuccessful attempts in the search for ultimate truths (as it is still seen by some “very modern” historians) but as the expression of certain time, place and environment; “true” for its time and place, though outlived later. Thus, for instance, in speaking about the decline of the Spartan state, he attributes its decline to “the growth of inequality of wealth.” Many other instances of this kind could be cited. It may really be said that “two souls fought in his breast”: a realist according to his method, an idealist and mystic in his general philosophy—that was the tragedy of Hegelianism!

Two obstacles were in Hegel’s way—two obstacles which were avoided by Marx and Engels. They were his system and his idealism.

“Systems” of philosophy are nowadays somewhat out of fashion. The universal acceptance of the theory of evolution, the mood of relativity prevailing in all branches of human thought, the theory of subjective unconscious motivation established by the New Psychology, have made “systems” not only impossible, but even somewhat ridiculous. We have done with the naive belief that some one philosopher will come along and solve all problems; discover all truths; establish once for all such ultimate principles that will make an end to all searchings after truth in the future. The time for philosophic systems has passed forever!

But in Hegel’s time the creating of a system of philosophy was just the thing for a philosopher to do. It was expected of him. This was the time of the great philosophic systems. A “system” must not only be all inclusive; it must not only be universal; it must also be monolithic; it must be one whole; rounded out, finished and closed, and therefore dogmatic. Behind the system-making lay, consciously or unconsciously, the thought of a finished universe, given once for all, of ultimate final truths that are to be discovered once for all.

All systems of philosophy, no matter how much they prided themselves on their critical spirit, no matter how vehemently they seemingly fought against dogmatism, always ended in dogmatism. Systems are, according to their nature, metaphysical (in the sense that Hegel used the word as opposed to dialectical). Hegel’s imposing structure was therefore rent by an inner contradiction. His dialectical method required open space, an open unfinished universe. It scorned final and ultimate truths. It viewed the universe as a constant process, as constant change, in which everything develops into something else, in which everything negates itself; in which quantities constantly create new qualities; a universe in which there is nothing final; nothing finished; in which truths become falsehoods, and falsehoods truths. A universe of this kind could not be squeezed into the narrow frame of a system. The two cannot house together. One has to choose between the two. Either one accepts the dialectic view and gives up all hope of ever creating a final system, or one sacrifices dialectic for system making. Marx and Engels chose the first alternative. They adopted Hegel’s dialectic method and left system making to those who have the time and the inclination for mental gymnastics. They had more important things to do—perfect this method and use it for their own purposes.

They had to perfect it before they could use it. Hegel’s dialectic was very imperfect because it was imbued with mysticism. This was the second great obstacle that prevented Hegel from making full use of his method. Here again the duality of Hegel’s thinking comes to the fore. He wanted to be objective. He believed that “as to nature, philosophy has to understand it as it is. The philosopher’s stone must be concealed somewhere in nature itself.” That sounds like a sentence from a materialistic book. He even thought that “Thought is the last product of the world process”. If thought is a product, and the last product at that, there must be causes, other than thought of which it is a product. It must consequently lead to the conclusion that consciousness (thought) is determined by the “world process”, or as Marx expressed it, “by social being”. But Hegel did not draw these logical conclusions; he was a thorough-going idealist, and, in spite of his dialectics, in spite of his objectivity, social being (or the world process) was for him determined by consciousness (idea). As an idealist he could not think otherwise.

IV. IDEALISM

Many are the sins of idealism. We need not dwell upon them now, but its original sin is that it reduces the world of reality to a world of shadows. “Literally idealism is the name for a philosophical doctrine,” explains Hoernle2 “a theory of reality in terms of ideas”. The world of reality, the world of “things” are for the idealist nothing but a reflection of some idea or spirit. Different schools of idealism gave different names to their “idea”, but whether one calls it idea, absolute idea, world spirit, or any other name, it comes to the same thing. Real is only the spirit; whatever is mundane, material, corporeal, is nothing but an emanation of the spirit. “Simple minded people” may think that they see houses, rivers, mountains, people, and that these things which they see, hear, touch, smell, are real objects outside of them. They think so only because they are “simple minded”, because they do not approach these things philosophically; the idealist philosopher knows better. “It is evident…that extension, figure, and motion are only ideas existing in the mind,” declares one of the greatest idealists, George Berkely.3 It is beyond Berkely’s understanding how sensible people could ever imagine that material world, the world of corporeal things in space and time does really exist outside of their minds. “It is indeed,” he says, “an opinion strangely prevalent among men, that houses, mountains, rivers, and in a word all sensible objects, have an existence natural or real distinct from their being perceived by the understanding…for what are the forementioned objects but the things we perceive, and what do we perceive besides our own ideas or sensations?”4

Berkely’s words are representative not only of his own philosophy but of idealism in general from Plato to our most recent idealists. When some of our present day philosophers felt an urge to return to the mystic, but for them comforting, philosophy of idealism, they turned to Berkely. Sir James Jean speaking about Berkely adds “Modern science, (that is “modern science”, as Jean interprets it, H.K.) seems to me to lead, by a very different road to a not altogether dis-similar conclusion.” He also believes, together with Berkely and all idealists, that the objectivity of things outside of us “arises from their subsisting in the mind of some eternal spirit.”5

This “eternal spirit” is also a very old “friend” of idealism. Idealism must either postulate some eternal spirit or come to the absurd idea of Solipcism.6

“Spirit” is necessary to idealism also for another reason. Philosophic idealism has always served the cultured parts of the ruling classes as a surrogate for religion. Religion is one of the most important pillars on which the class society rests, but the crude religion of the church, good as it may be for the masses, cannot satisfy the cultured. It is too primitive, too crude, too vulgar, if you please. The ideologists of the class society know well that something more refined, more “modern” must be found, to replace the old religion of heaven and hell; a new foundation is necessary for the old structure. Berkely knew very well what practical purpose his idealism must serve; he says: “So I shall esteem them (his own writing) altogether useless and ineffectual, if by what I have said I cannot inspire my readers with a pious sense of the presence of God”. So does Kant hope to make “reason prepare a way for faith”. Idealists of our own day are no exception to the rule; speaking in the name of science, such men as Jean, Eddington and others created a new idealism by way of which they arrived at a new idea of the old God. The reason for the religious mood of at least some of the scientific metaphysicians was stated by Bertrand Russell (himself a half-hearted idealist) in the following frank, even brutal, words:

“The reconciliation of religion and science which professors proclaim and bishops acclaim rests, in fact, though subconsciously, on grounds of quite another sort, and might be set forth in the following syllogism: science depends upon endowments, and endowments are threatened by Bolshevism; therefore science is threatened by Bolshevism, therefore religion and science are allies. It follows, of course, that science, if pursued with sufficient profundity, reveals the existence of a God.”7 “Bolshevism” is here inserted only because it is now fashionable. Idealism with its metaphysical God and refined prejudices, was always in mortal dread of the enemies of the established, whether they are called Bolsheviki or any other name. “Philosophy,” says John Dewey, meaning really idealist philosophy from which he himself is by no means free, “was…invented in a fanciful way in order to justify and preserve the existing social fabric…The sanction of traditional authority was its motive.”8 And we may add, so it has remained until to-day.

Hegel was a thorough-going idealist in spite of the seeming objectivity of some of his statements. “Spirit,” Hegel declares, “is the only reality. It is the inner being of the world. It is that which essentially is, and is per se.”9

What is this spirit that is the “only reality”, the “inner being of the world”? What is this eternal spirit, the spiritual substance, the absolute idea, about which the idealists of all schools speak so glibly? No one knows; idealists fill volumes about it, but cannot say what it is or how they come to know about it. One of the arguments most often advanced against materialism is that the materialists themselves do not know what matter is, and it is true, the materialist could no more say what matter is in itself, than the idealist could say what spirit is in itself. But, there is one very significant difference: while the materialist cannot say what matter is in itself, he can describe its properties and its behavior; he does know a great deal about matter, and what he knows about matter is scientifically proved; the truths of materialism are the products of scientific research and experiment, and are proved by centuries of human experience. The idealist cannot say the same about his spirit. It was born and reared in his own head. It is a creation of his own phantasy; the idealist needs a spirit, and therefore creates it.

What, for instance, is “spirit” for Hegel? It is universal reason, and universal reason is for him the reason of God. “Reason,” he says, “in its more concrete manifestation is God” and “God rules over the world, the contents of his rulings, the execution of his plans is universal history” (The philosophy of history). What is the dialectic process of history to Hegel? Nothing but the result of the dialectic process of the spirit.10 Ludwig Feuerbach was certainly right when he saw in Hegel’s philosophy the last hiding place for theology.

The great merit of the Hegelian philosophy, says Frederic Engels, is that “for the first time the whole world, natural, historical, intellectual, is represented as a process; i.e., as in constant motion, change, transformation, development.11 An attempt is made to trace out the internal connections that make a continuous whole of all this movement and development.” But, what is it that was changing, developing? For Hegel the idealist, it was the changing and development of the spirit. “To him the thoughts within his brain were not the more or less abstract pictures of actual things and processes, but conversely, things and their evolution were only the realized pictures of the idea existing somewhere from eternity before the world was.”12 Therefore Engels passes this harsh sentence on his teacher, “The Hegelian system in itself was a colossal miscarriage—but also the last of its kind.”

The inner contradiction of the Hegelian system made it possible to include within the Hegelian school people of the most diverse social and philosophical opinions. The conservatives have taken over his system and his idealism. “Some Hegelians maintained,” says Harold Hoéffding in his ‘History of Modern Philosophy’, “that rightly understood, the philosophy of their master accords with ordinary faith and the teaching of the church. Others declared that when logically carried out it is found to stand in irreconcilable antagonism to the latter.”13 Insofar as each side has taken only one element of the Hegelian structure, it was always right. The “Young Hegelians” could very well debate as to the real Hegelian. This was of no interest to Marx and Engels; they took from Hegel what in their opinion was valuable and revolutionary—his method—and left the metaphysicians and theologians to fight about the rest.

NOTES

1. Quoted by Plekhanof, in his notes to F. Engel’s “Feuerbach” collected works, Vol. VIII, p. 360.

2. R.F.A. Hoernle—“Idealism as a Philosophy”. P. 47.

3. “Principles of Human Understanding”. P. 9.

4. Ibid. Par. 4—P. 115; Open Court Edition.

5. “Mysterious Universe”. P. 147.

6. On the new developments of idealism, in connection with the discoveries in physics, see my article “Historical Materialism and the New Science”—Modern Quarterly.

7. The Scientific Outlook. P. 96.

8. Reconstruction in Philosophy. Chapter 1.

9. Phenomenology of the Mind. Preface English translation by J. B. Baillie.

10. N. Cunow, “Die Marxische Geschichts-Gesellshaffts und Staatstheorie”, Band 1, p. 224-252, The reader will find here an excellent exposition of Hegel’s social and historical views. See also Plekhanof’s excellent essay, “From Idealism to Materialism”, collected works, Vol. 18.

11. Engels: Socialism, Scientific and Utopian. P. 85.

12. Ibid, p. 86.

13. Vol. 2; p. 268.

Socialist Review began as American Socialist Quarterly in 1932. The name changed to Socialist Review in September 1937. The journal reflected Norman Thomas’ supporters “Militant” tendency of the ‘center’ leadership. Beginning in 1936, there were also Fourth Internationalists lead by James P. Cannon as well as the right-wing tendency around the New Leader magazine also contributing. The articles reflect these ideological divisions, and for a time, the journal hosted important debates. The magazine continued as the SP official organ through the 1940s.

For a PDF of the full issue: https://archive.org/download/radical-society_summer-1932_1_3/radical-society_summer-1932_1_3.pdf