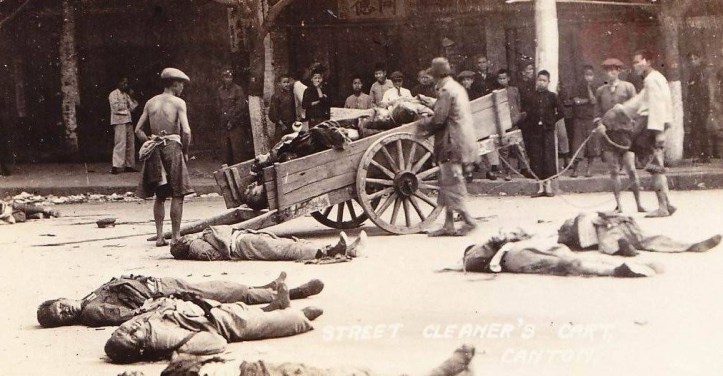

The First United Front, a policy central to the Comintern’s larger political perspectives in the mid-1920s was not just over, but a disaster in which thousands of the best Communist fighters in China were killed. The repercussions would roil both the International and internal lives of the Russian and Chinese parties for years. 1927 was a year that forever changed China and its Revolution. In April of that year anti-imperialist confrontations in Nanjing and imperialist military intervention signaled both greater strength of the anti-imperialist movement and imperialist resistance to China’s growing unification movement. Worried over militant and left ascendancy the KMT Right under Chaing-Kai-Shek turned his former Communist allies that formed the First United Front. In April, his Nationalist Army approached Shanghai to depose the militarist clique controlling the industrial city. Communist and Left KMT forces staged an uprising in the to wrest control before the National Army entered. As it entered, it shot down its former allies by the thousands, and a Civil War began within the Nationalists. The Left KMT, including Communists, regrouped in Wuhan and set up a rival Nationalist government. However, on July 15, 1927 the Left KMT Wuhan government, under military pressure from Chang, turned on their Communist allies purging them from the government and outlawing them. In August, the Comintern removed C.C.P. leader Chen Duxiu, who was blamed for the failure of the Comintern’s own policy of working within the Koumintang, and promoted a new leadership around Qu Qiubai. That new leadership was tasked with organizing an uprising, which would take place that December and would be known at the time as the Canton Commune. The crushing of the Commune also shifted the center of China’s revolution from the city to the countryside, and from the working class to the peasantry. The fallout in the Comintern were equally profound. Below is a report on the first Comintern leadership meeting after the December, 1927 defeat held in February, 1928.

‘The Chinese Question in the Plenum of the E.C.C.I.’ by R—ev from Communist International. Vol. 5 No. 8. April 15, 1928.

THE Plenum’s resolution on the Chinese question summarises the results of a complete period in the development of the Chinese revolution, the characteristic feature of which period is the fact that the workers’ and peasants’ movement carried on under the slogans of the Chinese Communist Party. The inadequate forces of the Chinese Communist Party, enfeebled by the white terror and losses in innumerable struggles, did not allow it the possibility of placing itself at the head of the movement everywhere. This was especially the case in regard to the peasants’ movement, which still largely bears an elemental character. None the less, one has to note that the peasants’ movement was of the greatest strength and most widespread wherever the Communists were at the head of it.

Communist Experience

After all this period, the Communist Party emerges enriched with enormous experience of the revolutionary struggle. A correct evaluation of this experience on the part of the Communist Party and the worker and peasant masses, provided the conditions of a sober estimate of the entire situation, the correlation of class forces in the country and the position of the workers’ and peasants’ movement be observed, is a highly important condition of the victorious development of the Chinese revolution. Meantime, it is the very fact that during the last stage of its development the movement carried on under the banner of the Chinese Communist Party, that the undivided hegemony of the Chinese revolution is now in the hands of the working class, that in its struggle against counter-revolution that class has already exploited the highest form of class struggle (armed insurrection) and during the course of that struggle put forward slogans which pass beyond the confines of a bourgeois-democratic revolution—it is these facts which have necessitated an attempt to reconsider the question of the very character of the Chinese revolution. Both in the documents of the Chinese Communist Party (the political resolution of the November Plenum of the C.C.P. Executive Committee) and in the speeches of individual comrades at the Chinese conference held on the eve of the E.C.C.I. Plenum the following theses were propounded: (1) the Chinese revolution is “developing or has already developed into a socialist revolution”; (2) the Chinese revolution is of a permanent character. This characterisation of the Chinese revolution at the given stage is erroneous not only by reason of the fact that it ignores many peculiar features of the Chinese revolution, and in the first place ignores its fundamental feature, namely that it is a revolution in a semi-colonial country, but also because it leads to highly dangerous and injurious practical deductions on the part of the Chinese Communist Party.

The character of the Chinese revolution is defined by those objectively historical tasks which arise out of the economic and political state of the country. In no circumstances is it permissible to draw the deduction that the actual character of the revolution has been changed from the fact that the Chinese bourgeoisie has passed over to the camp of reaction, that it has become the intellectual and practical protagonist of counterrevolution. The transfer of the bourgeoisie to the camp of counter-revolution simply signifies that the fundamental driving force of the bourgeois-democratic revolution is now the proletariat, which is called, together with all the mass of peasantry, to resolve the tasks of the revolution. Not one of these tasks is yet resolved and they will have to be resolved against the bourgeoisie, who have passed into the camp of the counter-revolution. It is obvious that in order to paralyse the opposition of the bourgeoisie, in order to strengthen the basis of the revolutionary-democratic dictatorship of the working class and the peasantry, the proletariat may find itself forced to confiscate the large enterprises. But to take these measures, indispensable as they may be in the process of carrying through a bourgeois-democratic revolution against the bloc of militarists, imperialists and Chinese bourgeoisie, as measures defining the character of the Chinese revolution at the given stage would imply the committing of a theoretical and practical error: would imply leaping over a large stage of development, the basic content of which are the agrarian revolution, the annihilation of the vestiges of feudalism, the uniting of China and the winning of its independence by the establishment of the revolutionary-democratic dictatorship of the working class and the peasantry.

The Nature of the Chinese Revolution

The definition of the Chinese revolution as one which has already developed into a socialist revolution arises from an extraordinary simplification and schematic treatment of all the prospects of development in the revolution. The question of the development of the bourgeois-democratic revolution into a socialist one will be decided in face of an extraordinarily complicated situation, both internally and still more internationally. The decisive factor in regard to the possibility of that development, and in regard to its tempo will be the question of the degree to which the working class will, by way of a radical accomplishment of the bourgeois-democratic revolution, succeed in drawing the great masses of Chinese toilers into the struggle against reaction and counter-revolution, and the degree to which the Chinese revolution will be safeguarded by the support of the world proletariat, and similar issues.

The characterisation of the Chinese revolution as a permanent revolution is still more erroneous. The significance which it is attempted to attach to the resolution of the November E.C.C.I. Plenum takes the following line: as there is no class in China other than the proletariat which can head the struggle for the achievement of the tasks of the bourgeois-democratic revolution, as the bourgeoisie do not represent serious class forces, as the objective situation is driving the. worker and peasant masses on to a decisive struggle, the Chinese revolution will develop unbrokenlv along a rising line, going on from victory to victory. The Comintern starts from the assumption that the Chinese revolution is actually developing along a rising line; but that does not mean that certain phases of the revolutionary struggle in which victory will be replaced by defeat and vice versa are entirely excluded. But meantime the characterisation of the Chinese revolution as a permanent revolution has already had its effect in an underestimation of the consolidation of the forces of reaction and in an incorrect evaluation of the correlationship between the workers’ and peasants’ movements, The characteristic of this very period in China is the fact that the first wave of the workers’ and peasants’ movement to rise under the slogans of the Communist Party has now fallen and that, as the E.C.C.I. Plenum resolution defines it: “At the present moment a new mighty rise of the masses’ revolutionary movement on a national scale is not yet in being, although a number of symptoms indicate that the workers’ and peasants’ revolution is moving towards such a rise.” The characteristic of the present moment is just the fact that while a further growth and development of the peasants’ movement is taking place, the workers’ movement is living through a temporary depression. Meantime, it is absolutely obvious that without a genuine rise in the workers’ movement the victory of the Chinese revolution is impossible, for only a rise in the workers’ movement can guarantee victory in the strategic points against the chief enemy of the Chinese revolution. While the adherents of the definition of the Chinese revolution as a permanent revolution set the chief emphasis on the question whether a direct revolutionary situation exists or does not exist in China, the resolution of the E.C.C.I. Plenum notes as the characteristic feature of the Chinese revolution that the movement is developing extremely unequally, both geographically, and in the sense of the correlation of the various columns.

The Prospects—and the Position of the Chinese C.P.

The E.C.C.I. Plenum indicated the following immediate prospect for the Chinese revolution. The Chinese revolution is moving on to a fresh rise of the revolutionary movement throughout the whole of China.

“This rise inevitably confronts the party with the immediate practical task of organising and accomplishing a massed armed insurrection, for only by way of insurrection and the overthrow of the present government can the tasks of the revolution be resolved.”

The soundness of this prospect is confirmed not only by the fact that the peasants’ movement is developing irresistibly in certain provinces, and that the revolutionary peasantry have succeeded in establishing a soviet government in certain provinces, but by the fact that the Chinese bourgeoisie, despite the support of the imperialists, has not succeed in dealing with the workers’ and peasants’ movement to the extent of preventing it from rising again. Despite the serious defeats which the working class has suffered, despite the fact that these defeats have made great breaches in the ranks of the Communist Party and the working class, the basic proletarian forces of the revolution are preserved. The Canton insurrection showed that these proletarian forces have grown to the extent of being able to provide examples of the greatest heroism, and that the Chinese proletariat have actually attained a genuine leadership of the Chinese revolution.

The prospect of a new rise in the Chinese revolution and of a preparation for mass armed insurrection demands an attentive and sober estimation of the correlation of forces inside the country and the situation of the workers’ and peasants’ movement. At the moment we are faced with the undoubted presence of a certain consolidation of the reaction in China. This consolidation is revealed not only in the fact that the forces of the counter-revolutionary camp have grown, thanks to the transfer of the bourgeoisie to the counter-revolutionary side, but also in the fact that despite all outbreaks of the workers’ and peasants’ movement the reactionary camp, though far from united internally, and torn by internal contradictions, acts compactly. There is also undoubtedly present a certain depression in the workers’ movement, evoked by defeats, by the extraordinary worsening of the position of the working class, the white terror, the disintegrating activities of bourgeois agents in the workers’ movement, and a weakening of Communist leadership. All the signs indicate that the chief danger threatening the workers’ and peasants’ movement in China consists in a split between its separate component elements; in a split between the Communist advance-guard and the working class, and in a split between the workers’ and the peasants’ movement. These splits are assisted by the mood which has developed inside the Communist Party, a mood which consists in the failure to understand the true relationship between the advance-guard and the masses of the proletariat. Only by preserving to themselves the support of the millions and dozens of millions of the Chinese workers and peasants can the Communist Party count on a really serious victory over the counter-revolution and the imperialists. But the simple fact that the Communist Party is the sole party actually struggling for the interests of the workers and peasants is insufficient. The Party must have continual contact with these masses, must educate them, organise and teach them to conquer. Meantime, the failure to understand this frequently leads the Communist Party in practice to the situation that, as the result of underestimation of the counter-revolutionary forces and the over-estimation of the importance of direct action, the Chinese Communist Party often organises a movement, a strike, demonstrations, insurrections, guerilla struggles which are foredoomed to defeat by reason of their inadequate connection with the masses and of work among those masses, by reason of the absence of a coordinated attack of the separate parts of the movement, and by reason, finally, of the absence of a sound combination of the political and technical preparations for the attack. Facts of this kind have been observable recently in various provinces of China. Hence arises the fundamental danger for the Chinese Communist Party: a danger which consists in their exposing their main forces to the blows of the reaction before the new wave of the workers’ and peasants’ movement is prepared and begun. For this reason the central point of the E.C.C.I. Plenum’s resolution is the question of the necessity for every-day steady activity among the great masses and their organisation around the Chinese Communist Party.

The main attention of the Chinese Communist Party must be given to the strengthening of their link with the working class. The E.C.C.I. Plenum indicated that the Party must resolutely put an end to the practice of exerting pressure on separate sections of the working class and must transfer all its energies to the work of convincing, of educating the working masses. Those elements of disintegration which are at present to be observed in the workers’ movement in China, their withdrawal from the revolutionary trade unions, the organisation of so-called brotherhoods, and in some places their going over to Chiang Kai Shek and other trade unions, confront the Party with the extremely difficult task of penetrating into these organisations and winning the workers over to their side. It is characteristic of the workers’ attitude that while they are not refusing to take part in direct attacks, at the same time they avoid maintaining an every-day connection with the revolutionary organisations or assisting them in their every-day work. This tells of the extraordinarily difficult conditions in which the Chinese Communist Party has to work, but it means that the Communist Party must establish such forms of contact with the masses of the working class as will not afford the counterrevolution the possibility of striking at sections of the revolutionary organisations.

Organising the Peasants

Despite the fact that the peasants’ movement is steadily growing, the task of organising the peasant masses is no less difficult than it is in relation to the working classes. The E.C.C.I. Plenum indicated the necessity of intensifying the work of setting up peasants’ organisations, while cautioning the Party against an increase in the guerilla attacks if they are inadequately prepared, do not have certain chances of success, or if they are not connected with the workers’ movement in the towns. Unquestionably the Chinese Communist Party must place itself at the head of the spontaneous movements of the peasantry, but its basic line of approach should be that only with a rise in the revolutionary wave both in the towns and in the villages can such movements be crowned with success. The Chinese Communist Party has to reckon with the peculiarity of the situation in various provinces, varying their tactic, adapting themselves to the special features, and so on.

The Chinese Communist Party, which during the comparatively short period of its existence has come through great trials, and having on the whole successfully outlived the great opportunist errors committed by the past leadership of the Communist Party, having succeeded in placing themselves at the head of the workers’ and peasants’ movement after the bourgeoisie had passed into the counter-revolutionary camp, having, despite a series of big defeats, succeeded in withstanding the pressure of the counter-revolution, is now faced with extremely complex tasks. Their achievement demands the maximum consolidation of the Party itself. That consolidation must take the line of outliving the “putschist” deviations in the Party and the advanceguardist deviations in the commission, and of consolidating the ranks of the Party, which have been seriously weakened in the revolutionary struggles, and increasing the size of the Party itself by drawing on those workers and peasant groups which have already developed and been tempered in the struggle against counter-revolution. The Party will have to correct its attitude in regard to the trade unions, adjusting their position when the party and trade union apparatus is in fact a single unit, and when the Communists compose the great majority in the local nuclei of the trade unions. The Party will have to continue the task of increasing the working class elements in its apparatus, guaranteeing an everyday connection with the workers and peasants. The Party must strengthen the discipline in its ranks, while at the same time establishing opportunities for taking stock of the attitude of the rank and file party masses and for their expressing their will. Also great ideological work will be necessary in order finally to outlive those moods which distract “its attention from preparing the millions of the masses for a fresh extensive revolutionary rise, preparation which provides the central task of the moment.”

The Canton Rising

The E.C.C.I. Plenum subjected to consideration the question of the lessons arising from the Canton insurrection. The supplementary information on the course of the insurrection since received entirely confirmed the estimate which was made before the Plenum at the E.C.C.I. Chinese conference. Unquestionably the Canton insurrection has and will have enormous importance in the development of the workers’ and peasants’ revolution in China. It demonstrated the great revolutionary maturity of the Chinese proletariat; despite all the errors which were committed in the preparation and carrying out of the insurrection it is an heroic example for the entire Chinese proletariat. But at the same time it revealed the existence of the following errors: An inadequate preliminary activity among the workers and peasants, as well as among the army of the opposition; an inaccurate approach to the workers who were members of the yellow trade unions; an inadequate preparation for the insurrection on the part of the Party and the Young Communist organisations themselves; a complete lack of information on events in Canton on the part of the all-China party centre; a feeble political mobilisation of the masses (an absence of extensive political strikes, the absence of an elected soviet as the organ of the insurrection in Canton). The prospect of a new rise in the revolutionary wave and of preparation for a mass armed insurrection obliges the Chinese Communist Party diligently to study the experience of the Canton insurrection and to make the results accessible to the broad mass of members of the Chinese Communist Party and to the workers and peasants of China.

The defeats suffered by the Chinese revolution provide food for the Trotskyist renegades, who declared the Canton insurrection to be a “putsch on the basis of a falling revolutionary wave.” This attitude is also to be found in smaller degree inside the Chinese Communist Party, but chiefly among those groups who were excluded from the ranks of the Communist Party for their Menshevist errors. At present liquidatorial attitudes find their expression in attempts to establish a new Menshevik party under the flag of the workers and peasants. If the renegades succeeded in creating such a party, its fate would be certain: in the situation of an intensified class struggle this party would inevitably be transformed into a plaything in the hands of the counter-revolution. The struggle against the counter-revolutionary party, as also the struggle against all forms of liquidatorial attitude, is one of the chief tasks of the Chinese Communist Party. The overcoming of the leftist-putschist deviations is a prerequisite to the swift, energetic and resolute suppression of all attempts to create such a Menshevik party.

None the less this touching union of the social democrats, of Tang-Ping-Shen and the Trotskyists in slander against the Chinese revolution is by no means accidental. The sole force in the whole world which is actually in practice assisting and will continue to assist the workers and peasants of China in their heavy struggle against the militarists, against the counterrevolutionary bourgeoisie and against world imperialism, is the Communist International; and the Communist International will have to exert all its energies in order to organise the masses of the world proletariat around the task of assistance to and support of the Chinese revolution.

The ECCI published the magazine ‘Communist International’ edited by Zinoviev and Karl Radek from 1919 until 1926 irregularly in German, French, Russian, and English. Restarting in 1927 until 1934. Unlike, Inprecorr, CI contained long-form articles by the leading figures of the International as well as proceedings, statements, and notices of the Comintern. No complete run of Communist International is available in English. Both were largely published outside of Soviet territory, with Communist International printed in London, to facilitate distribution and both were major contributors to the Communist press in the U.S. Communist International and Inprecorr are an invaluable English-language source on the history of the Communist International and its sections.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/ci/vol-5/v05-n08-apr-15-1928-CI-grn-riaz.pdf