James Sand writing for the exemplar of ‘American exceptionalism’, Jay Lovestone’s ‘Workers Age’ on Adolph Sorge’s ‘pioneering American exceptionalism.’

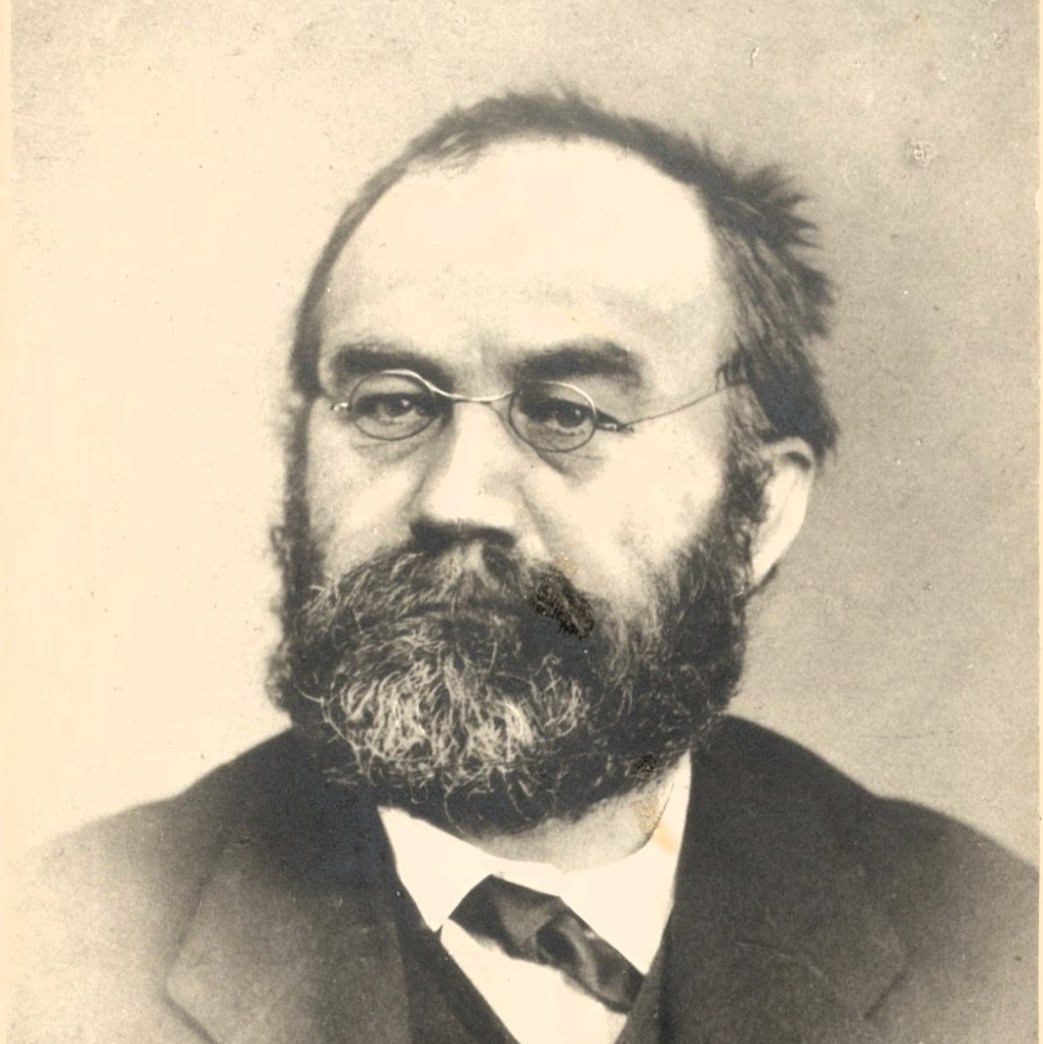

‘The First American Marxist: Friedrich Adolph Sorge’ by James Sand from Workers Age. Vol. 5 No. 1. January 4, 1936.

TO MOST OF THOSE WHO are familiar with the name of Sorge, it symbolizes little more than the man who acted as Marx’s rubber-stamp in America, to whom Marx and Engels wrote extensive letters on the labor movement here. To a select few it symbolizes the man who laid the First International to rest in Philadelphia in 1876. To be sure, the letters of Marx and Engels to him are known to be of great importance, as is Sorge’s clerical work in the International; but the man himself is not generally thought to have been a thinker or organizer in his own right. Yet it was he who first gave international organizational perspective to American workers, it was he who issued the stirring appeal to the international proletariat calling them to victory even in retreat after the Philadelphia burial, it was he who can without reservation be looked upon as the first great historian of American labor. In fact, many an academic reputation in labor history today rests upon wholesale translation or rephrasing of Sorge’s articles in the Neue Zeit during the nineties. He gave Marxism an American stamp and recognized the exceptional situation of American capitalism even in its early days. Next to Marx and Engels he was the foremost “American exceptionalist” in the early days of American labor. He foresaw with true genius the backwardness of the American worker, the reasons for it, and with Marxist foresight he laid down tactics for revolutionizing him as part of the historical task laid upon the vanguard of the American proletariat. Sorge was born in Saxony in 1827, and was reared in a revolutionary environment, his father’s house being a station on the underground railway for Polish revolutionaries. At the age of twenty-two he was in the Baden revolution of 1849, but escaped the sentence of death by departing. Switzerland expelled him, and refuge in Belgium was short-lived. Europe was thus closed to him. He found repugnant the idea of coming to live in America because it was a slave-owning country, but there was no other place for him to go, and he came here in 1852.

Sorge was not a worker in the sense of an artisan. He was a son of the bourgeoisie, but like Marx and Engels, and later Lenin, he transvaluated bourgeois ideals and became a class conscious proletarian. In America he made his living as a music-teacher, and for this he was often called to task by the workers who could not understand the place of intellectuals in the labor movement. Marx himself faced this same fight against the Bakuninists and successfully won out. So did Sorge in America.

Weitling’s conception of strategy, tactics, and principles Sorge quickly disowned and he would have none of him or his ideas. Sorge was a leading member of the Communist Club of New York which was formed in 1857, and after the Civil War he was an organizer of a League for Germ.an Freedom and Unity among the radical German expatriates here. He was a leader in the formation of the North American Workingmen’s Association which he succeeded in having affiliated with the First International. This he also urged and had succeed in the National Labour Union. At the Hague Congress of the International in 1872 when the anarchists were expelled, Sorge was made corresponding secretary and later when the General Council was moved to New York he became general secretary.

At the Hague Congress he joined with Marx against the anarchists particularly in the fight against their opposition to democratic centralism. In the discussion he said: “The partisans of autonomy say that our Association does not need any head; we think, on the contrary, that the Association is very much in need of a head, and one with plenty of brains inside it.”

Stekloff in his History of the First International has latterly given currency to the mistaken notion that Sorge was merely a tail to the Marxist kite. He says, rather patronizingly, “Marx and Engels had implicit faith in Sorge, and their confidence was well served, for Sorge was of a thoroughly trustworthy disposition and was whole-heartedly devoted to socialism.” But Sorge’s copy-book of correspondence with the General Council which he kept as secretary of the American branch even before the Hague Congress shows him to be an original mind. In August 1871 he gives three reasons why the class-consciousness of the American worker has not kept pace with the development of capitalist production:

“(1) The great majority of workingmen in the Northern States are immigrants. having left their native countries for the purpose of seeking here that wealth which they could not obtain at home. This delusion transforms itself into a sort of creed, and employers and capitalists take great care in preserving this self-deception among their employees; (2) The Reform Parties…These parties assert that the emancipation of labor or rather the welfare of mankind can be obtained peacefully and easily by universal suffrage, glittering educational measures, benevolent and homestead societies, universal language and other schemes nicely put up in their innumerable meetings and carried out by nobody. The leading men of said parties. mostly men of science and philanthropists, perceive the rottenness of the governing classes as far as relating to their own ideas of morality, but they see only the surface of the question of labor and accordingly all their humanitarian advices do not touch but the exterior of it, Such a reform movement well advocated and intelligibly presented to the workingmen is often gladly accepted, because the laborer wants to ameliorate his position and does not perceive the hollowness of that gilded nut shining before his eyes; (3) The third obstacle is and has been the wrong guidance of the labor movement Itself. A number of the so-called leaders have been actuated by ambition or other selfish motives, whilst another number was honest and true but failed to take the right steps and began to reform, all reforms finally taking their abode in one of the political parties of the ruling class, the bourgeois.”

Finally in 1876, after a lingering existence of four years the First International was put to rest, Sorge closing its books and storing its documents away. Before giving the International Working-Men’s Association to history, however, an appeal was written to the international proletariat. This document is obscure, but should be one of the cherished documents of the proletariat tradition.

“Fellow-Working-Men:

“The international convention at Philadelphia has abolished the General Council of the International Working- Men’s Association, and the external bond of the organization exists no more.

“The International is dead!’ the bourgeoisie of all countries will again exclaim, and with ridicule and joy it will point to the proceedings of this convention as documentary proof of the defeat of the labor movement of the world. Let us not be influenced by the cry of our enemies! We have abandoned the organization of the International for reasons arising from the present political situation of Europe, but as a compensation for it we see the principles of the organization recognized and defended by the progressive working ‘men of the entire civilized world. Let us give our fellow-workers in Europe a little time to strengthen their national affairs, and they will surely soon be in a position to remove the barriers between themselves and the working men of other parts of the world.

“Comrades! you have embraced the principle of the International with heart and love; you will find means to extend the circle of its adherents, even without an organization. You will win new champions who will work for the realization of the aims of our association. The comrades in America promise you that they will faithfully guard and cherish the acquisitions of the International in this country until more favorable conditions will again bring together the working-men of all countries to common struggle, and the cry will resound again louder than ever: ‘Proletarians of all countries, unite!’”

The next year Sorge had a hand in the formation of the Socialist Labor Party, and he kept in active touch with the labor movement all the years of his life. In New York he influenced Strasser and Laurell, the teachers of Samuel Gompers, and Gompers’ own belief in trade-unionism comes directly from Sorge. To Gompers’ credit let it be said that he appreciated Sorge’s gifts and even acknowledges a debt to him in his autobiography.

The establishment of the Neue Zeit under the editorship of Karl Kautsky found Sorge an associate editor along with Lafargue, Bernstein, Engels, Bebel. To the periodical Sorge contributed articles on the United States, and especially noteworthy are those on the history of labor movement, already mentioned. The whole span of American history, from 1800 to 1880 is Sorge’s province in them, and he puts himself in the class of Marx and Engels in his understanding of the significance of the historical development of American capitalism and the American proletariat. He shows himself an interpreter not only of the past and present of American labor, but also of its future. His estimation of the American Federation of Labor before it was even a decade old is uncanny in its accuracy of description as well as in its delineation of the line to be pursued by Marxists in relation to it. He said:

“The Federation is a bona fide, a true labor organization, an organization of wage workers, without clauses and back doors in its statutes through which middle class and wealthy capitalists, would-be reformers and politicians, might creep in. With all its faults and defects, the American Federation of Labor is the representative of the working class, of the proletariat of this country and as such, it is to be respected; but it has, also, to fulfill a great task. The federation deserves considerable merit for many a good work done for the working class of these United States. Under strong opposition the federation made an end to the nonsensical fight about high protective tariff and free trade in its own ranks; it has mightily advanced the aspirations for shorter work hours; it has favorably influenced the legislation for the protection of the working people; it has, without interruption, pushed the indispensable organization of the wage-workers; it has protected and guarded the right of labor to open, manfully-acting organization, against the secret form, in a long struggle, and has expressed the duty of the wage workers to carry on their struggle with open weapons.

“The federation has also shown economic intelligence by considering the formation of trusts, syndicates, etc., as a natural consequence of the industrial development, and by its refusal to join in the chorus of stupid howlers…As a matter of fact, the federation did not permit itself to be made the end of experiments by the American mushroom reformers and sectarians of all sorts. Although its class consciousness is not yet sufficiently developed, it must be declared that the American federation has represented the class position and guarded the class character of its organization. The federation’s struggles have been class struggles.”

Sorge died in 1907, laden with years, nearly eighty, but not with the honors that will ultimately be his in a workers’ America.

Workers Age was the continuation of Revolutionary Age, begun in 1929 and published in New York City by the Communist Party U.S.A. Majority Group, lead by Jay Lovestone and Ben Gitlow and aligned with Bukharin in the Soviet Union and the International Communist (Right) Opposition in the Communist International. Workers Age was a weekly published between 1932 and 1941. Writers and or editors for Workers Age included Lovestone, Gitlow, Will Herberg, Lyman Fraser, Geogre F. Miles, Bertram D. Wolfe, Charles S. Zimmerman, Lewis Corey (Louis Fraina), Albert Bell, William Kruse, Jack Rubenstein, Harry Winitsky, Jack MacDonald, Bert Miller, and Ben Davidson. During the run of Workers Age, the ‘Lovestonites’ name changed from Communist Party (Majority Group) (November 1929-September 1932) to the Communist Party of the USA (Opposition) (September 1932-May 1937) to the Independent Communist Labor League (May 1937-July 1938) to the Independent Labor League of America (July 1938-January 1941), and often referred to simply as ‘CPO’ (Communist Party Opposition). While those interested in the history of Lovestone and the ‘Right Opposition’ will find the paper essential, students of the labor movement of the 1930s will find a wealth of information in its pages as well. Though small in size, the CPO played a leading role in a number of important unions, particularly in industry dominated by Jewish and Yiddish-speaking labor, particularly with the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union Local 22, the International Fur & Leather Workers Union, the Doll and Toy Workers Union, and the United Shoe and Leather Workers Union, as well as having influence in the New York Teachers, United Autoworkers, and others.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/workers-age/1936/v5n01-jan-04-1936-WA.pdf